Giving new life to classic old songs

As someone who’s passionate about music, I’ve always gotten a special kick whenever I hear new recordings of favorite classic rock songs that have been enhanced by the presence of guest vocalists.

Sometimes this occurs in the studio when an artist has chosen to re-record a track with another famous voice added to the mix. Other times, it’s a live recording from a concert performance, where a celebrity is brought out on stage to do a duet or provide harmonies. In one memorable instance, a half-dozen luminaries joined Bob Dylan on stage taking turns on verses of one of his classic ’60s tunes at an anniversary concert.

Providing a new ingredient in a tried-and-true musical recipe can result in some tasty moments, but it can’t be denied there are examples of this practice that might be called “failed experiments,” when the addition of the guest vocals not only doesn’t add anything but instead diminishes the song in question.

More often than not, though, it can be an exhilarating new wrinkle on an old tune.

I have spent a few hours this past week locating and listening to mostly recent recordings on which vintage artists have successfully infused their classic rock tracks with vocals by other vintage artists. I’ve selected a dozen here for your listening enjoyment, which you can hear by tuning in the Spotify playlist at the end as you read about how these performances came to be.

**************************

“These Days,” Jackson Browne and Gregg Allman, 2014

A special event at the Fox Theatre in Atlanta nine years ago gathered a broad array of musicians to celebrate the songs and voice of Gregg Allman — and just in time, as it turned out, because Allman passed away in 2017 at age 69. Everyone from Susan Tedeschi and Keb’ Mo’ to Vince Gill and Dr. John turned out to offer spirited covers of Allman’s tunes and, in a few cases, sing them with Allman himself. The best of the bunch, in my view, is Jackson Browne’s stunning duet on “These Days.” Browne wrote it when he was just 16, eventually recording it for his 1973 LP “For Everyman,” and Allman recorded his own version for his solo debut “Laid Back,” which was released almost simultaneously. “He made that song twice as good as it was before,” said Browne of his friend’s rendition. More than 40 years later, they teamed up to perform the song together, using Allman’s arrangement. It appears on the 2014 release “All My Friends: Celebrating the Songs and Voice of Gregg Allman.”

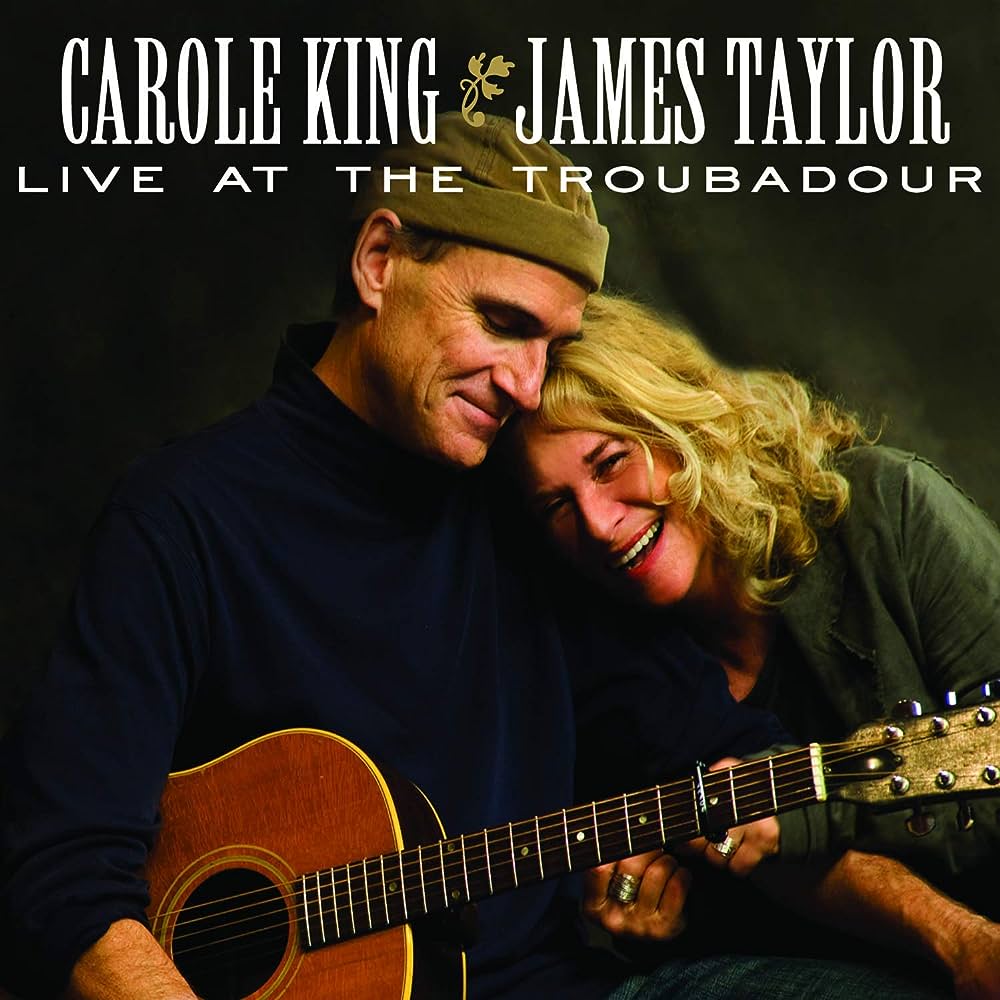

“You’ve Got a Friend,” James Taylor and Carole King, 2007/2010

Taylor and King first met in 1969 in L.A. and musically bonded almost immediately. By 1970, King was playing piano on Taylor’s breakthrough “Sweet Baby James” LP, and they ended up performing together at The Troubadour club in Hollywood that year. When Taylor heard King working on songs that would appear on her upcoming “Tapestry” album, he was knocked out by “You’ve Got a Friend” and asked if he could record it as well, and she graciously agreed. Taylor’s rendition became an enormous #1 hit in 1971 from his “Mud Slide Slim” LP. In 2007, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of The Troubadour, Taylor and King reunited there for six historic shows, and their “Live at the Troubadour” album came out three years later as they mounted a hugely successful reunion tour. They took turns performing their old songs, and then did a heartfelt collaboration on “You’ve Got a Friend” near the end.

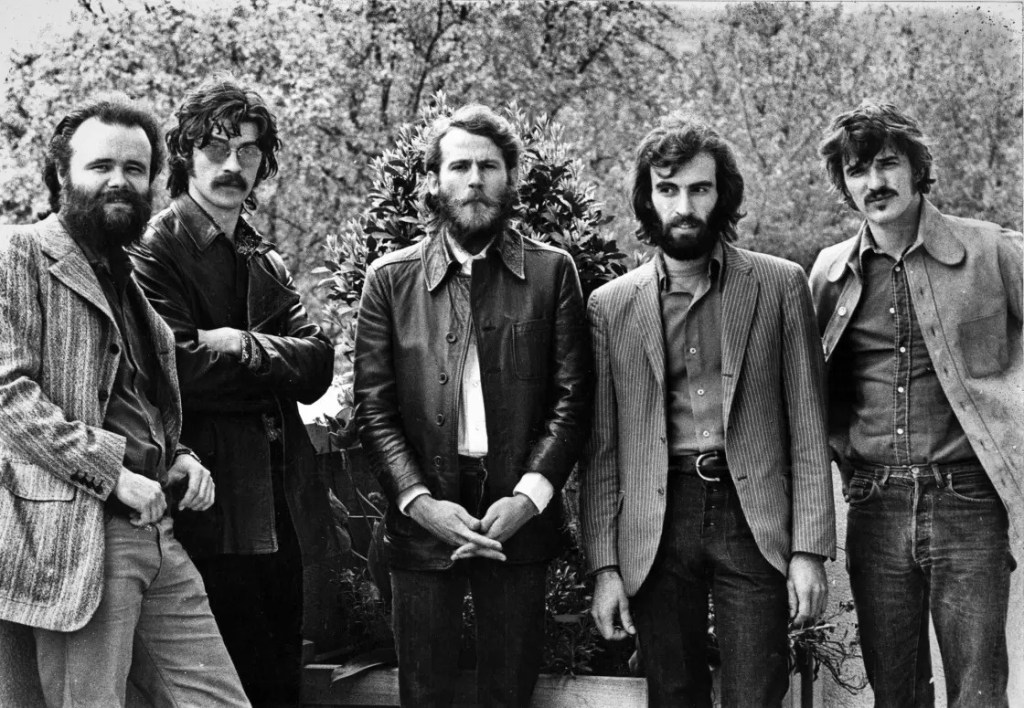

“Black Water,” The Doobie Brothers with The Zac Brown Band, 2014

Back in 1974, The Doobies released “Another Park, Another Sunday” as their next single, but it didn’t get much attention until radio stations started playing the B-side instead, a country-ish ditty by guitarist Pat Simmons called “Black Water.” It became the group’s first #1 hit and their fourth of 10 Top Twenty hits during their career. In 2014, Simmons, Tom Johnston, Michael McDonald and John McFee chose to invite country artists like Brad Paisley, Toby Keith, Blake Shelton and Sara Evans to join them in the studio for remakes of a dozen of their hits. It’s great fun to hear the whole “Southbound” LP, but for this playlist, I’ve singled out the new version of “Black Water” featuring additional vocals by Zac Brown Band.

“Riders on the Storm,” Ray Manzarek, Carlos Santana and Chester Bennington, 2010

Wondrous guitarist Santana had found a winning formula in 1999 and 2002 when he teamed up on original material with singers like Dave Matthews, Rob Thomas, Michelle Branch and Seal on two successive albums that both topped the charts. In 2010, Santana took a slightly different tack when he released “Guitar Heaven,” an album featuring the maestro covering classic rock songs like “Sunshine Of Your Love,” “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” and “Whole Lotta Love” with a variety of rock vocalists. The whole album is a treat to listen to, but the one that stands out for me is The Doors’ “Riders on the Storm,” on which Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek provided the underpinning while Linkin Park vocalist Chester Bennington filled in for the late Jim Morrison. It’s a different arrangement, but I think it rivals the 1971 original from The Doors’ “L.A. Woman” album.

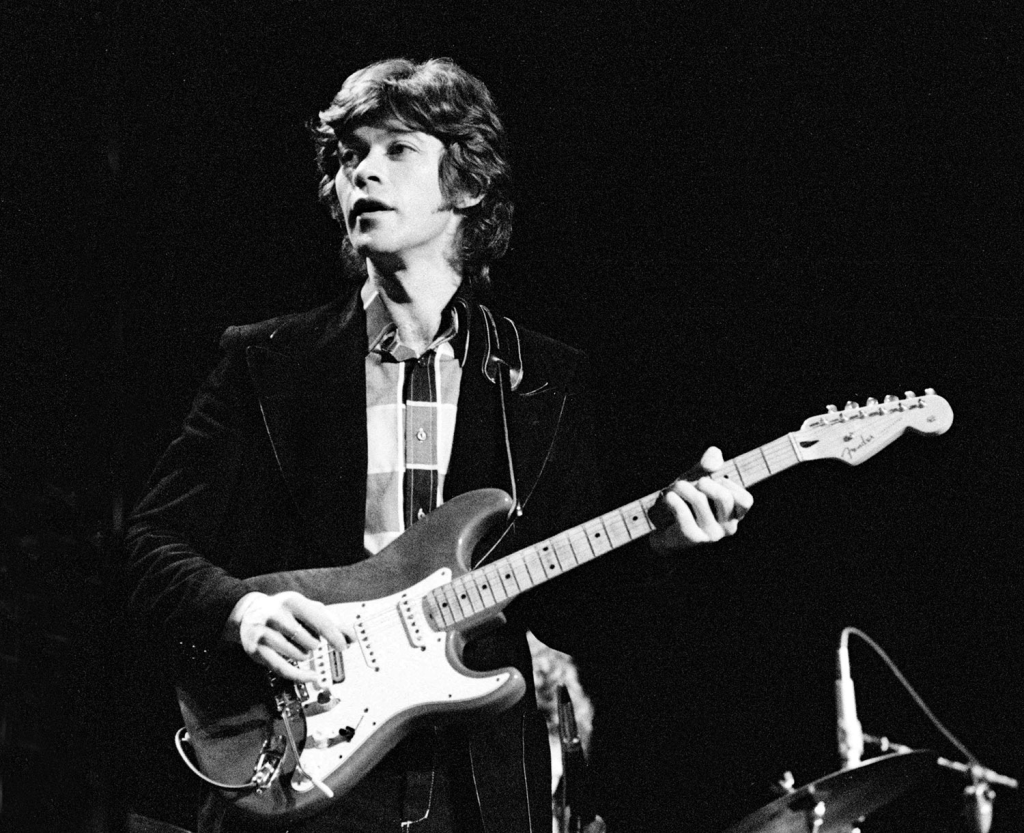

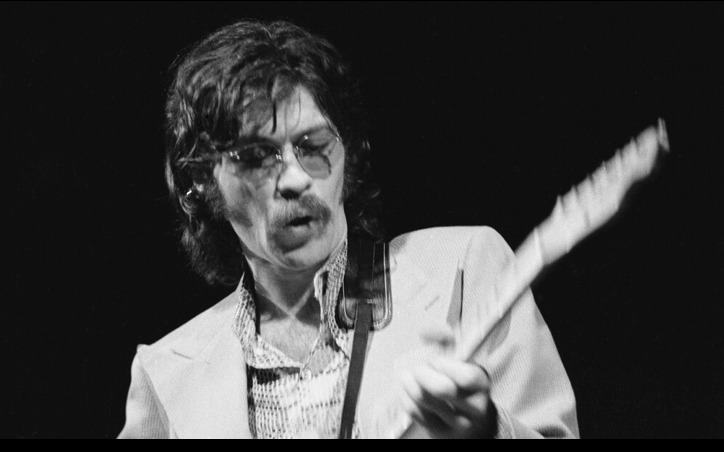

“Forever Man,” Eric Clapton with Steve Winwood, 2008/2009

Back in 1966, when Clapton was forming Cream with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, he hoped to bring Winwood into the band as well, but the keyboardist/vocalist was in the midst of forming Traffic and declined. Three years later, Clapton and Winwood managed to join forces as Blind Faith, but that lasted for only one album and a short tour. Each musician went his own way for decades, each enjoying successful solo careers before finally reuniting in 2008 for a much-acclaimed extravaganza at Madison Square Garden. They performed more than 20 songs from throughout their careers, including some Blind Faith tracks and Traffic and Cream classics, and released 21 songs on a live LP in 2009. One of the album’s gems is “Forever Man,” a Clapton solo single that reached #26 in 1985 (and #1 on the Mainstream Rock Tracks chart ) and is augmented here by Winwood’s fine vocals on alternating verses.

“Questions,” Stephen Stills with Judy Collins, 2017

The star-crossed career arc of Buffalo Springfield ended in 1968 with their third and final album, “Last Time Around,” on which most tracks were recorded separately without the full band together. One of those was Stills’ tune “Questions,” virtually a solo song. Stills re-purposed sections of it for the second half of the Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young track “Carry On” on their “Deja Vu” album. Nearly a half-century later, Stills joined up with former paramour Collins (for whom he had written “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes”) for an album, “Everybody Knows,” and a modest tour, and “Questions” was one of the songs Stills chose to include, with Collins adding her distinctive voice.

“Fortunate Son,” John Fogerty with Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band, 2009

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Foundation was founded in 1984, and its Museum opened in Cleveland in 1995. A quarter-century after its founding, the Foundation staged two All-star shows at Madison Square Garden to commemorate the milestone, and a multi-CD collection came out a few moths later. The headliners — Stevie Wonder, U2, Jeff Beck, Aretha Franklin, Crosby Stills and Nash, Paul Simon, Metallica and Springsteen — each invited various other Hall of Fame inductees to participate with them on various classic rock tracks. During Springsteen’s set the first night, the great John Fogerty of Creedence Clearwater Revival took the stage and delivered an impassioned reading of the CCR anti-war screed “Fortunate Son” (a #3 hit in 1969) with The E Street Band providing some stellar backup, including Springsteen’s vocals.

“Gimme Shelter,” The Rolling Stones with Lady Gaga, 2012/2023

In 2012-13, The Stones mounted their “50 and Counting” tour, marking their 50 years in the music business. Their December 2012 show in Newark was originally recorded for a pay-per-view concert, then remixed and released 10 years later in February 2023. The band had invited a few guests to appear on selected songs, including John Mayer, Gary Clark, The Black Keys and Bruce Springsteen. By far the most riveting performance came from Lady Gaga, who was still a relative newcomer at that point with just two albums out (although both multi-platinum). She came on early in the proceedings to handle the female vocal part on “Gimme Shelter,” performed so superbly by Merry Clayton in 1969 on the “Let It Bleed” album.

“Mother and Child Reunion,” Paul Simon with Jimmy Cliff, 2012/2017

Simon had been intrigued with the rhythms coming out of Jamaica in the late ’60s, and made a half-hearted attempt at a reggae song with Art Garfunkel called “Why Don’t You Write Me” on their “Bridge Over Troubled Water” album. Two years later, he wisely concluded that if he wanted to nail the Jamaican rhythms accurately, he needed to go to the source. He flew to Kingston and hired reggae star Jimmy Cliff’s band to record “Mother and Child Reunion” with him for his “Paul Simon” solo debut, and the single reached #4 in early 1972. It has been a regular part of his concert repertoire over the years, but in 2012 at a concert in Hyde Park in London, he brought Jimmy Cliff himself on stage to flesh out the vocal harmonies on the song. A CD/DVD of the show was released in 2017.

“Let It Be,” Dolly Parton and Paul McCartney, 2023

Last year, Parton said she felt sheepish and uncomfortable when notifgied she was being inducted into the Rockm and Roll Hall of Fame. She’s a titanic star of country music, of course, and has maybe a half-dozen songs in her recorded catalog that might be loosely described as rock, but she didn’t feel deserving of the honor. “If I’m going to be inducted, I’m going to need to make a rock and roll album,” she insisted, and set out to do just that. “Rockstar,” due for release in November, will include 30 selections involving everyone from Sting and Elton John to Miley Cyrus and Joan Jett. The preview single released last week pairs Parton with Paul McCartney on “Let It Be,” also featuring Ringo Starr on drums and Peter Frampton on guitar. It’s an exciting arrangement nicely executed.

“Luck Be a Lady,” Frank Sinatra with Chrissie Hynde, 1994

Sinatra was in his mid-70s when he was approached by his record label about putting together a record of duets with easy-listening peers and contemporary artists. He liked the concept, and lined up an impressive list of singers who were eager to participate, but he got cold feet when the time came to enter the studio. He had always been very particular about who was in the room when he was being recorded and, ultimately, he decided that he would sing the songs by himself with an orchestra and his duet partners would be recorded remotely and added after the fact, which has only recently become technically possible. Among the contemporary artists who “phoned in” their parts for Sinatra’s “Duets” (1993) and “Duets II” (1994) LPs were Willie Nelson, Jimmy Buffett, Bono and Aretha Franklin. I’m partial to The Pretenders’ Chrissie Hynde’s contribution to “Luck Be a Lady” from the second collection.

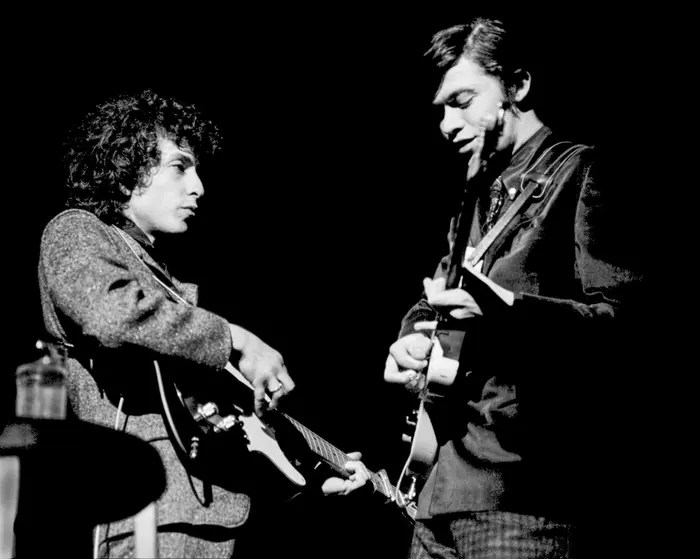

“My Back Pages,” Bob Dylan with Roger McGuinn, Tom Petty, Neil Young, Eric Clapton, George Harrison, 1992/1993

In 1992, the typically taciturn Dylan agreed to be feted at a commemorative concert celebrating his 30th anniversary as a recording artist. An extraordinary array of artists descended on Madison Square Garden to perform 30 Dylan songs from throughout his career — hits and obscure tracks, chestnuts and recent tunes. Among the 75 different musicians and singers on stage at various points of the evening that night were Stevie Wonder, Lou Reed, Chrissie Hynde, Richie Havens, Johnny Winter, Tracy Chapman, Eddie Vedder, Johnny Cash, Mary Chapin-Carpenter and John Mellencamp. As the show drew to a close, Dylan came out to perform three songs, and the best of these, the prescient “My Back Pages,” featured Roger McGuinn, Tom Petty, Neil Young, Eric Clapton, George Harrison and Dylan each taking a verse. It’s a thrilling confluence of talent sharing the spotlight on an iconic song from 1964. The CD was released in 1993, with a deluxe CD/DVD package re-released in 2014.

***************************