All under one roof

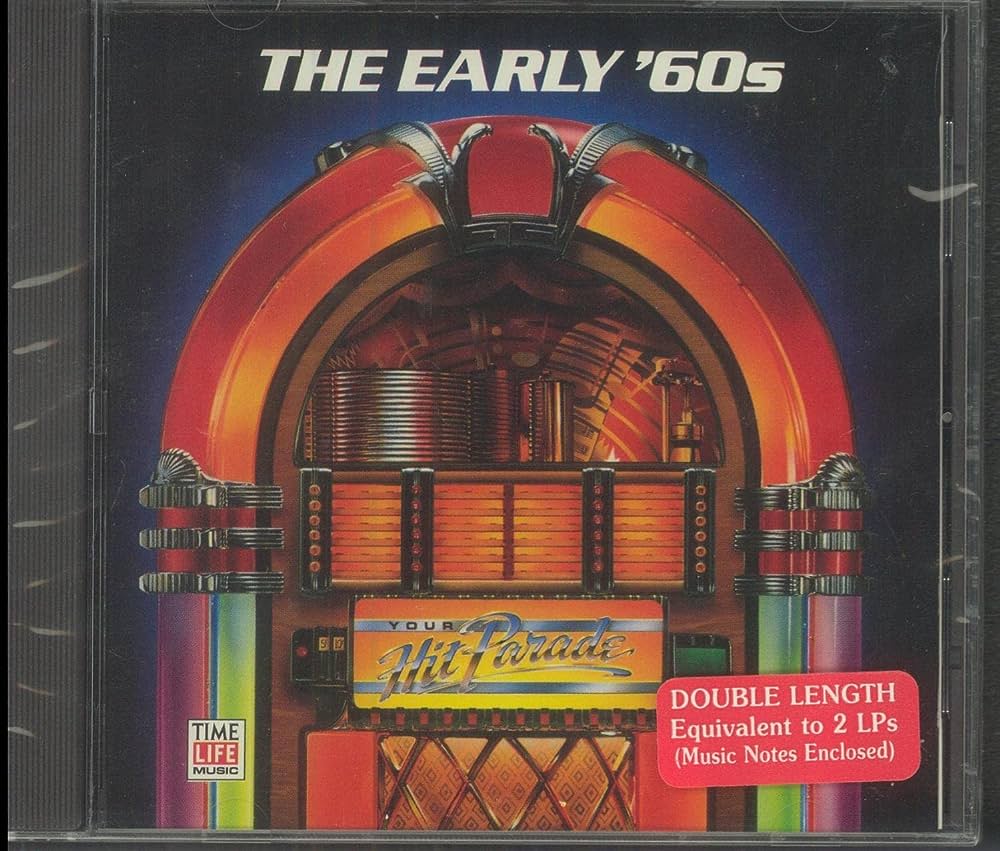

The generally accepted narrative of rock and roll’s first decade goes something like this:

1955-1958: Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Buddy Holly and others successfully merged blues, country, gospel and swing into an exciting new hybrid dubbed rock and roll, which was embraced by teenagers coast to coast and sold millions of records in that period. But plane crashes, arrests, military service and a conservative backlash combined to stymie careers and quash the momentum of rock and roll’s early successes.

1964-1969: The arrival of The Beatles and other British bands heralded a resurgence of vibrant rock music, which grew exponentially through the rest of the ’60s, with such sub-genres as garage rock, psychedelic rock, blues rock and country rock each enjoying growth and popularity.

The era between those two periods is typically disparaged as a forgettable wilderness during which rock had become tame and whitewashed, dominated by non-threatening teen idols and “girl groups.”

While there is truth in these generalizations, the early ’60s period certainly had its stellar moments, thanks in large part to the songwriting teams employed in New York City publishing companies who churned out many dozens of classic tunes that dominated the airwaves of that relatively innocent era when lyrics focused on idealized romance and adolescent anxieties.

One such publishing Mecca was known as the Brill Building, a Midtown Manhattan structure that housed dozens of music publishers, all competing to come up with the next big hit for the nation’s pop music charts. Although songwriters worked in a number of different buildings in the city, it was the 11-story office tower at 1619 Broadway near 49th Street that became known as the epicenter of the music industry for many years, serving as a magnet for the most prolific and successful pop music composers of that period.

If you were a musician at the Brill Building in, say, 1962, you could pick out a brilliant new pop song, have it arranged, cut a demo, and make a deal with radio promoters — all under this one famous roof. The 11-story, Art Deco Brill Building — 1619 Broadway, at 49th St. — became known as a one-stop shop for recording artists, but above all as an almost mythical place for songwriting.

Here, hundreds of high-quality hits were cranked out in an almost assembly-line fashion for girl groups, R&B luminaries, teen idols and more. Together, Brill Building songwriters conjured up a soundtrack for the “Mad Men” era — a playlist that in many cases would prove timeless. Granted, these writers turned out their share of teen-oriented drivel, but at their best, they married the excitement and urgency of rhythm-and-blues music to the brightness of mainstream pop.

The roster of songwriting talent under contract there was fairly astonishing: Carole King, Gerry Goffin, Burt Bacharach, Hal David, Neil Sedaka, Howard Greenfield, Barry Mann, Cynthia Weil, Jeff Barry, Ellie Greenwich, Neil Diamond, Mort Shuman and Doc Pomus. Readers surely recognize names like Carole King, Neil Sedaka, Burt Bacharach and Neil Diamond because they went on to become accomplished performing artists in their own right, but the others worked in relative anonymity even as they composed some of the most popular songs in American music history.

Let’s consider Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, one of three Brill Building songwriting teams comprised of married partners. In the tradition of the earlier Tin Pan Alley period of the ’30s and ’40s and early ’50s, these teams would split duties, with one composing the music while the other came up with the lyrics. Together, Barry and Greenwich pooled their talents, and the result was an impressive list of chart successes recorded by various artists of that time: “Da Doo Ron Ron” and “Then He Kissed Me” by The Crystals; “Be My Baby” and “Baby, I Love You” by The Ronettes; “Chapel of Love” and “People Say” by The Dixie Cups; “Maybe I Know” by Lesley Gore; “Leader of the Pack” by The Shangri-Las; “Do Wah Diddy Diddy” by Manfred Mann; “Hanky Panky” by Tommy James and The Shondells; and “River Deep – Mountain High” by Ike and Tina Turner.

Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, another prolific married couple who worked in the Brill Building for a few years, generated many hit singles in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, none more famous than The Righteous Brothers’ two monumental #1 hits, “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling” and “(You’re My) Soul and Inspiration.” The songwriting duo also penned “On Broadway,” a smash for The Drifters and, later, George Benson; “Kicks” and “Hungry,” both Top Ten hits for Paul Revere and The Raiders; “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” by The Animals; “Uptown” and “He’s Sure the Boy I Love” by The Crystals; “My Dad” by Paul Petersen; “I Just Can’t Help Believing” and “Rock and Roll Lullaby” by B.J. Thomas. In the late 1980s, two of their songs — “Somewhere Out There” by Linda Ronstadt and James Ingram, and “Don’t Know Much” by Ronstadt and Aaron Neville — won major Grammy awards.

Weil died in June of this year at age 82.

The Gerry Goffin-Carole King song catalog is probably the most well known of the Brill Building successes, thanks to the recent popularity of the stage show “Beautiful” about Carole King’s life. Together, they wrote these Top Ten hits: “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” by The Shirelles; “Take Good Care of My Baby” by Bobby Vee; “The Locomotion” by Little Eva; “Up on the Roof” and “Some Kind of Wonderful” by The Drifters; “Go Away Little Girl” by Steve Lawrence; “One Fine Day” by The Chiffons; “Chains” and “Don’t Say Nothing Bad About My Baby” by The Cookies; “I’m Into Something Good” by Herman’s Hermits; “Don’t Bring Me Down” by The Animals; “Pleasant Valley Sunday” by The Monkees and “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” by Aretha Franklin.

I’ve written recently about the many hits by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, in the wake of Bacharach’s death earlier this year: “What the World Needs Now is Love,” “(They Long to Be) Close to You,” “I Say a Littler Prayer,” “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” “Do You Know the Way to San Jose,” “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,” “Walk On By,” “One Less Bell to Answer,” “This Guy’s in Love With You.”

Mort Shuman and Doc Pomus found Top Ten success as a team beginning in 1958 with “A Teenager in Love” by Dion and The Belmonts, followed by “This Magic Moment,” “I Count the Tears,” “Sweets for My Sweet” and “Save the Last Dance for Me” by The Drifters; “Surrender,” “Little Sister” and “His Latest Flame” by Elvis Presley; and “Can’t Get Used to Losing You” by Andy Williams.

Neil Diamond, of course, wrote “I’m a Believer” and “A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You” for The Monkees, plus dozens more that he recorded himself (“Cherry Cherry,” “Shiloh,” “Kentucky Woman,” “Holly Holy,” “Solitary Man,” “Thank the Lord for the Night Time”).

Neil Sedaka, too, composed many songs (sometimes with Howard Greenfield) while working as a Brill Building professional songwriter, but he recorded all of them himself simultaneously during that early ’60s period (“Oh Carol,” “Calendar Girl,” “Happy Birthday Sweet Sixteen,” “Breaking Up is Hard to Do”).

The whole environment was creatively charged, said King in 1978. Some of the music publishers, notably impresario Don Kirshner, would pit one songwriter against another to have them compete for whose song would be selected by the performing artist he had in mind. “It was a pressure cooker,” said King, “but kind of in the same way that pressure cookers can produce fabulous meals, the system often pushed us to do our best work.”

I recommend you check out Ken Emerson’s 2006 book “Always Magic in the Air: The Bomp and Brilliance of the Brill Building Era,” which goes into great detail about the amazing Brill Building songwriters and the songs they created. Admittedly, some of the tunes listed above haven’t aged well. Indeed, some were even kind of cringeworthy at the time (“My Dad” by Paul Petersen?), but most are worthwhile entries in any rock music history lesson, and have been revisited and covered by other artists in subsequent decades.

So, a tip of the hat to the Brill Building, still around today, for providing the environment where these songwriting teams could work their magic in a 9-to-5 setting!

**************************