Smoke and lightning, heavy metal thunder

(When a friend recently asked me if I’d ever written a blog entry about heavy metal, I recalled having written this piece back in 2015, the first year of “Hack’s Back Pages.” I dug it up and found that it still holds together pretty well. I don’t think I can I improve on it much, and since most of my readers today probably weren’t reading the blog back then, I’m running it again this week. I hope you get something from it.)

***************************

I was 15 in the fall of 1970 when I met this strange, edgy girl in my suburban Cleveland neighborhood, a girl who would later be among those labeled as Goth — dark eye makeup, dark clothes, a creepy, nihilistic attitude. She invited me to her house to listen to albums, which was one of my favorite activities, so I accepted…except her albums were nothing like my albums, and her room was lit with about a dozen candles and creepy wall hangings.

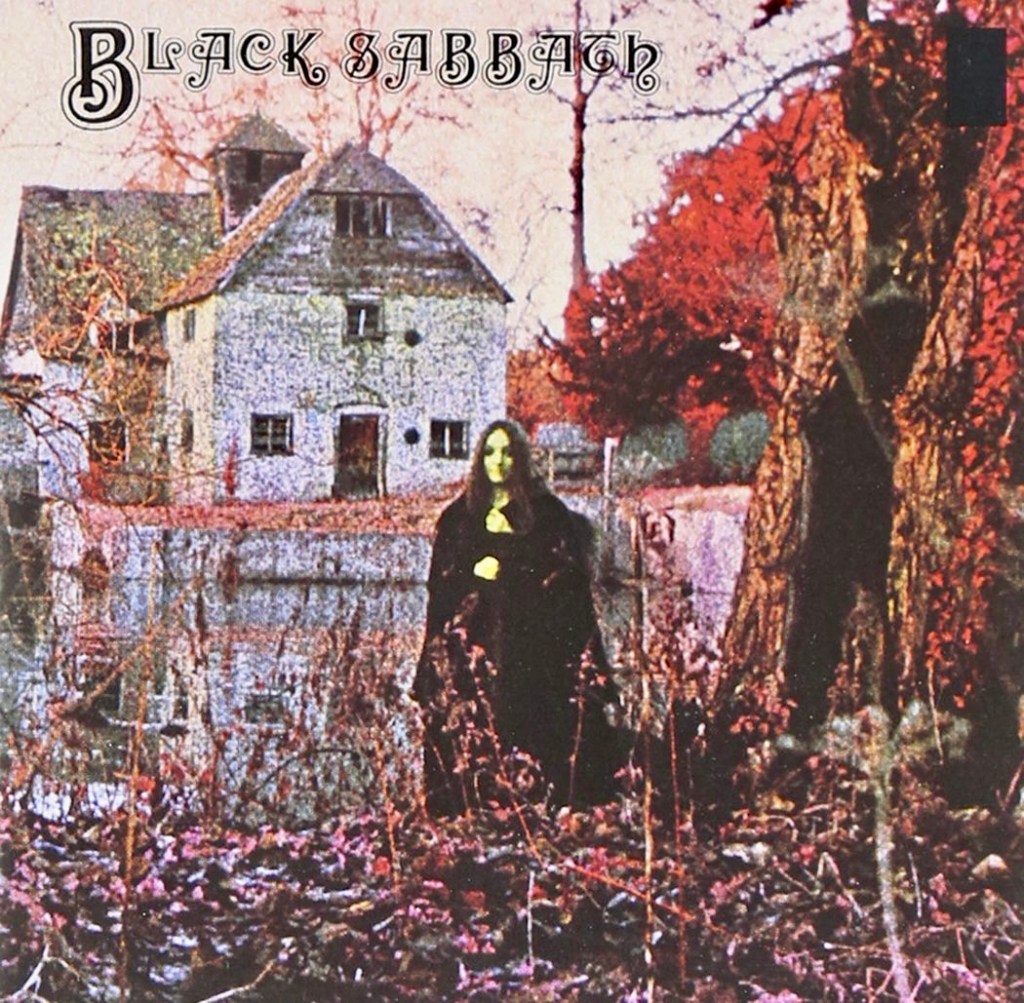

As I looked through her collection, I asked her to play me her latest favorite, and she lowered the needle on a song called “Black Sabbath,” the leadoff track from the album Black Sabbath by the band Black Sabbath. The cover showed a sinister-looking woman lurking in the woods, with an old building behind her. And the “music” — well, it was the sound of a thunderstorm, with a church bell tolling ominously in the distance. What the hell is this? I thought. And then the band came crashing in with these weighty, frightening chords, evoking a sense of doom and death. I got chills up my spine.

“What is this that stands before me??” The vocals seemed to grab me by the throat and demand my attention. I found it unnerving, but mesmerizing, and it went on for more than six minutes. “Oh no no, please God help me,” the vocalist implored, followed by more sledgehammer chords, first slow and plodding, then eventually triple-time with bass and guitar in unison, drums wailing, before it all came to a cataclysmic, sudden conclusion.

Holy shit.

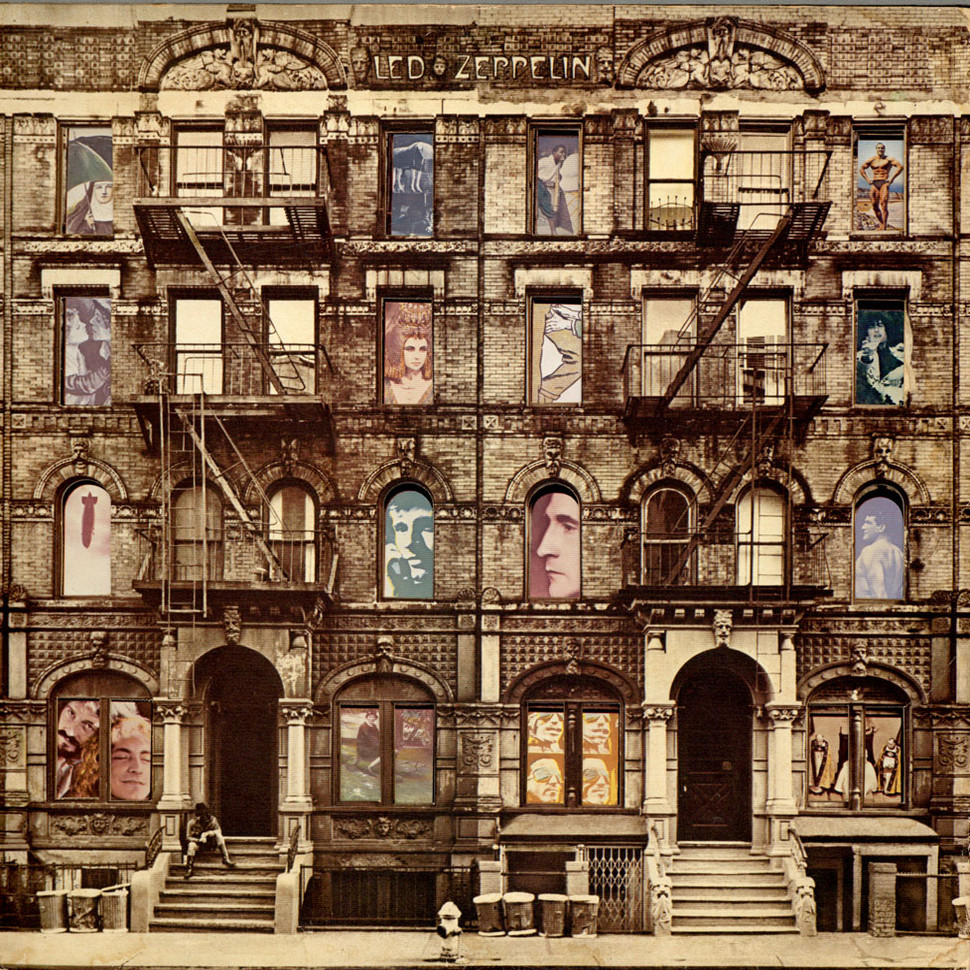

I’d heard and enjoyed plenty of heavy blues and psychedelic rock — Cream, Hendrix, early Zeppelin — but this was something else entirely. It kind of scared me, like it was evil, possessed. I thanked the girl for her hospitality and scurried home, where I put on something comforting like “Sweet Baby James” to make the dark vibes go away.

I didn’t really know it at the time, but I was hearing one of the earliest examples of a new genre of rock music: Heavy metal.

Full confession: This is not for me. I like to think I’m willing to keep my ears open to all kinds of music, but it was readily apparent to me early on that this was not my cup of tea, even when I was a 15-year-old awkward teen, supposedly the prime demographic for it.

Why didn’t I like it? Well, I’m into melody and harmony, and the subtle nuances of great singing, contagious rhythm and impressive instrumental passages. Heavy metal isn’t interested in any of that, and the most ardent fans will tell you so. “F–k melody, just give me volume,” was the bold appraisal of AC/DC’s lead vocalist Bon Scott before he died in 1980 of alcohol poisoning, known in British parlance as “death by misadventure.”

Even heavy metal artists and fans will concede that, for them, it’s all about high volume and heavy distortion, less syncopation, more showmanship, long guitar solos, tons of brute force. It’s what one critic called “the sensory equivalent of war.” It’s a duel between the lead vocalist and lead guitarist as to who can get the most attention. The tone of voice as an instrument in the mix is far more important than what the lyrics are about, which is probably a good thing, because the lyrics are overwhelmingly dark and depressing — “personal trauma, alienation, isolation from society, nasty side effects of drugs, the occult, horny sex, a party without limits.” And this isn’t me talking; it’s a summary from Ozzy Osbourne, sometimes referred to as the Godfather of Heavy Metal.

The 31-year-old son of a good friend is a devoted metalhead, and he offered this opinion: “After jazz, it was the genre that got me into playing drums and opened my mind to other forms of ‘not so mainstream’ music. Slipknot, Underoath, Slayer… Their live shows were unlike any other…just a sea of throbbing heads, aggressive, sweaty, loud, not giving a f–k about what people thought about you. Deep down I will always be a hardcore metal kid.”

Another friend, now in his 50s, was more pragmatic about it: “There can be something very cathartic and powerful about heavy metal. It appeals to lost or outsider kids, mostly, I think. Sometimes it just fits the bill. It got me through lots of cold, lonely walks across campus. You have to be of the right age and mindset… One thing about metal I never got into, though, was the cartoonish ‘evil’ imagery and stupid vibe of the lyrics, which were really kind of laughable.”

It’s not clear exactly when and how the term “heavy metal” came to describe this genre. Scientists refer to various elements like zinc, mercury and lead as heavy metals, which can be toxic but can be nonetheless important to our health in small quantities. The iconoclastic author William Burroughs used the term in his early ’60s novels “Naked Lunch” and “The Soft Machine.” The ’60s band Steppenwolf used it in their biker anthem “Born to Be Wild” in 1968 to describe the thrill of riding a noisy chopper down the highway at breakneck speed.

Metal was born in the late ’60s, when bands like Deep Purple, Blue Cheer, The Stooges and even Led Zeppelin were pushing the boundaries of blues and hard rock to become even more thunderous, more caocophonous, more chaotic. It could be rugged or mysterious, but rarely both at the same time, and hardly ever frightening. Then Black Sabbath arrived to change the game. Ozzy Osbourne and Company, originally known as Earth, went over to the dark side with a foundation built on thick, simplistic power chords, tempos that shifted from dirge-like to frenetic, desperate vocals spewing despairing words, and a relentless, basic bass/drums underpinning.

Geezer Butler, bass player for Black Sabbath, recalls, “In some review of our first album, someone called us ‘heavy metal’ as an insult. It said, ‘This isn’t music. It sounds like a load of heavy metal crashing to the floor.'” Lemmy Kilmister, the leader of the British metal band Motorhead, said: “For me, it needs to be big and it needs to be loud. In a club, you can have conversations over bands that are playing jazz or pop, or even hard rock. Nobody can ever have a conversation over my kind of music. Once we start, you listen or you leave.”

Osbourne, who named his band after a Boris Karloff movie, is remarkably matter-of-fact about the darkness of it at this point in his life. He said in 2010: “In the beginning, we decided to write scary music because we really didn’t think life was all roses. So we decided to write horror music. We never dealt with the occult ourselves, but all these nutters started sending us letters, and it kind of freaked us out. If you play with the dark stuff long enough, bad shit happens.”

The audience for heavy metal has typically been white teenage boys struggling to make their way in a world that they think doesn’t want them. Critic Jon Pareles said this: “As long as ordinary teen white boys fear girls, pity themselves, and are permitted to rage against a world they’ll never beat, heavy metal will have a captive audience.” Ronnie James Dio, vocalist for Sabbath after Osborne’s departure, had this to say: “Heavy metal is an underdog form of music because of the way you dress, how you act, what you listen to. So you’re always being put down. It’s this edgy, angry music, and because it pigeonholes the bands and their fans, together we feel strength with each other.”

It was also, let’s not kid ourselves, about sex and drugs. Bad boy Ted Nugent, now a poster boy for the far right, had disparaging things to say about those who liked his brand of music: “I toured more for the girls and the sexual adventure than for the music. If all I had was looking at those unclean heathens in the front row with their lack of personal hygiene and stenchy clothes, I’d take up crocheting.”

The reason heavy metal fans became known as “headbangers” is the tendency among fans (and band members too) to aggressively bang their heads in the air to the beat as they absorbed the music. Think “Wayne’s World” at its most crazed.

Heavy metal remained pretty much a fringe genre for nearly a decade, as punk, disco and New Wave dominated, with the occasional exception like Kiss’s “Rock and Roll All Nite” and “Beth,” both top ten singles in 1975 and 1976. But then, beginning in the ’80s, bands such as AC/DC, Def Leppard and Quiet Riot not only packed stadiums but went to the very top of the album charts with “Metal Health,” “Pyromania” and “For Those About to Rock We Salute You.” Between 1983 and 1984, heavy metal albums grew from 8% to 20% of the albums sold in the US market. At the three-day US Festival that year, the Heavy Metal lineup of Ozzy, Van Halen, Scorpions, Motley Crue and Judas Priest drew by far the largest crowds.

The rise of MTV beginning in 1981 helped the heavy metal snowball continue to grow, with outrageous music videos of sex and drugs and rock and roll at its most decadent and hedonistic. Iron Maiden, Saxon, Guns ‘n Roses, Metallica, Poison, Ratt, Megadeth, Anthrax and others sold millions of albums and concert tickets, thanks in large part to the constant exposure of their videos. And their audience widened; astute observers recognized that metal fans were no longer exclusively male teens but also college grads, pre-teens and, curiously, females (despite the often mysogynistic lyrics).

Eventually, the monolithic heavy metal audience became fractionalized. Hard core fans dismissed some bands as “light metal” and fed the desire for more extreme versions. If you Google “heavy metal,” you’ll see more than a dozen subgenres of metal that claim a share of this audience: Thrash metal, death metal, power metal, doom metal, gothic metal, sludge metal, rap metal. Even folk metal and Christian metal (really?). Each emphasizes one facet of the sound or lyrics more than the next.

Heavy metal in all its permutations remains a powerful force in the new millenium among the same audience it has always attracted — teenaged, disenfranchised, mostly male, alienated, pissed off. There’s a whole slew of newer bands (Bullet for My Valentine, Korn, System of a Down, Linkin Park, Mastodon) to keep the genre alive, but some of the veterans are still cranking out new material. Even Black Sabbath (the original lineup, including Ozzy) had a #1 album in 2013 with their reunion album, “13.”

For those who are curious, I highly recommend “Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal” by Jon Wiederhorn and Katherine Turman. Many of the quotes included here were gleaned from their comprehensive book.

Clearly, many rock music fans will never like heavy metal. One music-loving friend summed it up by saying, “I love my rock and roll loud, but I would rather stick a hot poker in my ear than have to listen to metal. And I don’t want to leave a concert covered with bruises.”

Illegal drugs and violent images aside, it’s a mostly harmless escape, a way to isolate in a sonic bubble with like-minded outcasts for a little while. In that way, it’s not all that different from other niche genres like opera, or progressive rock, or Australian folk music: It’s definitely not mainstream…but maybe that’s the whole point.

****************************