Give me some water, cool cool water

Water has been an essential commodity since before man walked the Earth. Communities have been founded based on their proximity to fresh water. It’s been said man can go weeks without food but no more than three or four days without water. Nearly 75 percent of our planet’s surface is covered with water…but that’s salt water. As the parched sailor in the middle of the ocean would say, “Water, water everywhere, and not a drop to drink.”

So many sayings involving water can be found in literature and contemporary discourse: Like a fish out of water. Keep your head above water. Still water runs deep. Spending money as if it were water. Blood is thicker than water. Makes your mouth water. Water over the dam. Throw cold water on something. Blown out of the water.

These days, we’re all reminded of the dangers of dehydration, and are urged to drink eight 8-ounce glasses of water daily. Indeed, we may someday fight wars over access to fresh water.

Songwriters have written many dozens of songs with lyrics about water, and I’ve identified 15 from the classic rock era (plus another baker’s dozen of honorable mentions) that I think you’ll find worthy of your attention.

*************************

“Dirty Water,” The Standells, 1966

This garage-band classic was written by producer Ed Cobb in 1966 as a mock paean to Boston and its then-polluted harbor and the Charles River. The song, recorded by The Standells and reaching #11 on US pop charts that year, was inspired partly by an incident when Cobb was mugged during a Boston visit. Despite its negative connotations, “Dirty Water” has been embraced by the city in the years since, particularly by its rowdy sports fans, thanks to the line, “Oh-h, Boston, you’re my home” at end of each chorus. The song has often been played at Bruins hockey games and Red Sox games following victories. In 1979, British garage band The Inmates recorded a raucous cover of “Dirty Water,” substituting “River Thames” and “London” for “River Charles” and “Boston.”

“Hell & High Water,” The Allman Brothers Band, 1980

Most rock bands go through peaks and valleys during their career, but perhaps no group has had a wilder roller-coaster ride than The Allman Brothers Band. From early struggles to critical praise, from tragic deaths to #1 albums, from drug busts and addiction to multiple rebirths in the ’90s and beyond, these guys have seen it all. In the early ’80s, they were in a trough with two lackluster albums on Arista Records (the terrible album cover of “Reach For the Sky” was an indication), but there were moments of that old spark, like Dickey Betts’s song “Hell & High Water,” which actually chronicles the group’s up and downs up to that point: “We’ve been through hell and high water, ready to go through it all again, /As long as we’ve got a quarter between us all, we’re gonna have money to spend…”

“Walk on Water,” Eddie Money, 1988

Between 1977 and 1988, Edward Mahoney, better known as New York rocker Eddie Money, released seven albums that reached between #20 and #70 on US charts. He also fared quite well on various singles charts with hits like “Two Tickets to Paradise,” “Baby Hold On,” “Think I’m in Love,” “Maybe I’m a Fool, “Take Me Home Tonight” (in a duet with Ronnie Spector) and “I Wanna Go Back.” His final Top Ten entry was 1988’s “Walk on Water,” written by former Sammy Hagar keyboardist Jesse Harms, in which the narrator frustratingly asks what he has to do to regain his lover’s trust: “Well I’m no angel, now I’ll admit, I made a few bad moves I should regret, /If I could find some way to prove, if I could walk on water, would you believe in me? /My love is so true…”

“Smoke On the Water,” Deep Purple, 1972

The iconic opening guitar riff and indelible hard rock groove made “Smoke on the Water” a landmark hit in 1972-73, and Deep Purple’s highest charting song. Its lyrics tell the true story of how the entertainment/casino complex on the Lake Geneva shoreline in Montreux, Switzerland, accidentally burned down one evening in 1971 during a Mothers of Invention concert, the night before Deep Purple were due to begin recording an album there. As the first verse and chorus put it: “Frank Zappa and the Mothers were at the best place around, but some stupid with a flare gun burned the place to the ground, /Smoke on the water, a fire in the sky…” The song was released on their “Machine Head” album in 1972, then reached #4 on US pop charts when released as a single in 1973.

“Bring Me Some Water,” Melissa Etheridge, 1988

Kansas-born Etheridge was discovered playing clubs in Pasadena and grabbed attention right out of the gate with her 1988 debut LP and its single, “Bring Me Some Water.” Her confessional lyrics, pop-based folk-rock, and raspy, smoky vocals have sustained her through an impressive career that has featured a dozen Top Twenty LPs and a half-dozen high-charting singles in the 1990s and 2000s. Even though her handful of singles in 1993-1995 charted higher, I’ve always returned to “Bring Me Some Water and its heartbreaking exuberance: “Somebody bring me some water, can’t you see I’m burning alive?, /Can’t you see my baby’s got another lover, and I don’t know how I’m gonna survive, /Somebody bring me some water, can’t you see it’s out of control?…”

“Heavy Water,” Jethro Tull, 1989

Chemically, heavy water is a form of water that contains a “heavier” hydrogen isotope that makes it ideal for production of nuclear power and weaponry. In the Tull song from the 1989 LP “Rock Island,” Ian Anderson was actually referring to acid rain, a type of precipitation with low pH levels caused by sulfur dioxide emissions that can have harmful effects on plants and animals. “On my first trip to New York in the summer of 1968, everyone else was running from the rain, and I realized it was because each drop of was leaving a dirty black mark. It was raining coal and sulfur!” The lyrics are bleak — “Thumping in my heart, and it’s hurting me to see, /Smokestack blowing, now they’re pouring heavy water on me” — but are offset by a sprightly, accessible melody and tempo that stand tall in the band’s latter-day catalog.

“Black Water,” The Doobie Brothers, 1974

Guitarist/singer Pat Simmons provided a lighter country element to The Doobies’ brand of ’70s rock and roll, offering homespun songs like “South City Midnight Lady” and “Tell Me What You Want.” His catchy track “Black Water” was an easygoing acoustic tune originally released as the B-side to Tom Johnston’s “Another Park, Another Sunday,” single, but a disc jockey in Roanoke, Virginia, began playing it because of the Blackwater River that ran not far outside the city. The intense regional interest caught the record label’s attention, and they re-released it as an A-side single, which made it all the way to #1 in March 1975. The lyric was actually written during a visit to New Orleans, with a reference to the Mississippi River and wanting to “hear some funky Dixieland.”

“Madman Across the Water,” Elton John, 1971

Lyricist Bernie Taupin, fascinated by mental illnesses, adopted the fractured imagery and detached thought process of an asylum inmate for this mind-bending title track from Elton John’s 1971 LP. The song had been originally recorded in 1970 with Bowie cohort Mick Ronson on lead guitar and intended for inclusion on his “Tumbleweed Connection” LP, but instead “Madman” was reimagined a year later using the orchestral flourishes of Paul Buckmaster’s dramatic strings arrangement, Elton’s compelling vocal delivery and Davey Johnstone’s understated guitar work. I think it’s one of the most riveting songs in his entire catalog. When American critics assumed the title referred to then-President Nixon from a Brit’s point of view, Taupin whistled and said, “Wow, that is genius. I never would’ve thought of that.”

“Bridge Over Troubled Water,” Simon and Garfunkel, 1969

This monumental tune is so ingrained in pop music culture that it’s hard to imagine a time when it didn’t exist. But in November 1969, a rapt audience at Carnegie Hall in New York listened as Art Garfunkel performed the song for the first time, six weeks before its release as one of the biggest singles of the year, and their response was thunderous rapture. Garfunkel sang it alone with Larry Knechtel on piano, and the recording of it, finally released 40 years later in 2009 on “Live 1969,” is presented here. Simon had been inspired by gospel singer Claude Jeter’s line, “I’ll be your bridge over deep water if you trust in my name,” coming up with his own gospel classic later covered by Aretha Franklin, Roberta Flack, Elvis Presley and dozens of others.

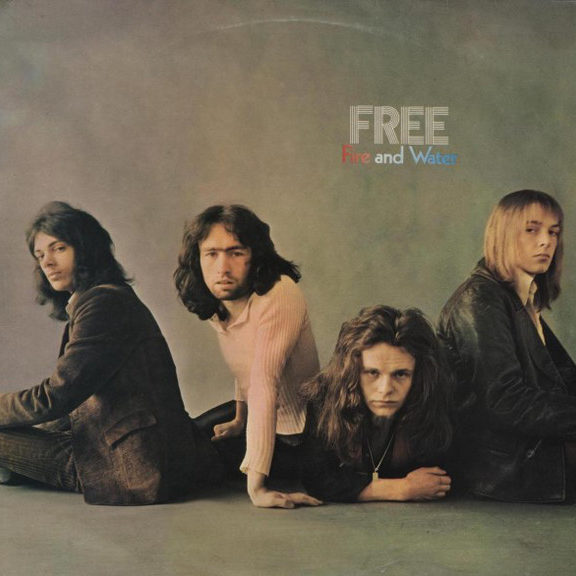

“Fire and Water,” Free, 1970

Vocalist Paul Rodgers and troubled guitarist Paul Kassoff were the linchpins of Free, one of England’s best yet underrated rock bands of the 1968-1972 period. (Rodgers and drummer Simon Kirke later went on to form the more commercially successful Bad Company.) “All Right Now,” which reached the Top Ten in a dozen countries in 1970, got most of the attention, although “Oh I Wept,” “Stealer” and “Wishing Well” also got airplay. The title track to Free’s third album, “Fire and Water,” does a nice job of examining the yin and yang of romantic relationships: “Lover, you turn me on, but quick as a flash, your love is gone, /Baby, I’m gonna leave you now, but I’m gonna try and make you grieve somehow, /Fire and water must have made you their daughter, /You’ve got what it takes to make a poor man’s heart break…”

“Water of Love,” Dire Straits, 1978

This track from the Dire Straits 1978 debut LP is a sterling example of the kind of haunting ballads guitarist/songwriter Mark Knopfler was writing in juxtaposition with the more uptempo hits like “Sultans of Swing” and “Lady Writer” in the band’s early years. His languid guitar work and seductive arrangement on “Water of Love” complements the clever melancholy of lyrics, which notes how both water and love are essentials in life: “I’ve been too long lonely and my heart feels pain, crying out for some soothing rain, /I believe I have taken enough, yes, I need a little water of love, /Water of love deep in the ground, but there ain’t no water here to be found, /Some day, baby, when the river runs free, it’s gonna carry that water of love to me…”

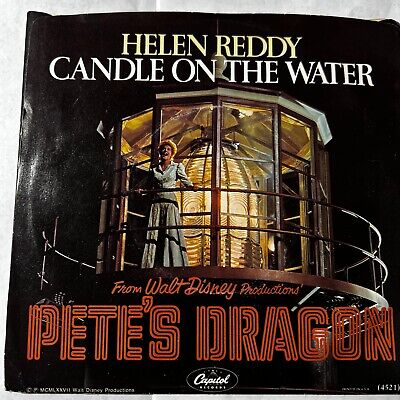

“Candle on the Water,” Helen Reddy, 1977

The original script for “Pete’s Dragon” was written in the 1950s for the Disneyland TV series but was shelved until its reimagining as a live action/animated musical film released in 1977. Popular Canadian singer Helen Reddy was tapped to not only sing the featured song “Candle On the Water” but as one of the film’s actors as well. The song, written by Al Kasha and Joel Hirschhorn, was nominated for a Best Song Oscar, and a slightly different arrangement by Reddy’s label got airplay on Adult Contemporary stations. The writers said they deliberately placed religious and spiritual symbols in the lyrics: “I’ll be your candle on the water ’til every wave is warm and bright, /My soul is there beside you, let this candle guide you, /Soon you’ll see a golden stream of light…”

“The Water is Wide,” James Taylor, 1991

This Scottish folk song was first written in the mid-1800s and has undergone many changes in lyrics and musical structure since then. Its hymn-like melody and modern lyrics published in 1905 have become widely accepted as definitive, exploring how love often wavers between exhilaration and heartbreak: “Oh, love is handsome and love is fine, the sweetest flower when first it’s new, /But love grows old and waxes cold, and fades away like summer dew…” A host of major artists have offered their interpretations: Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Fred Neil, Steve Goodman, Karla Bonoff, Bob Dylan, Barbra Streisand, Eva Cassidy, Cowboy Junkies and a collaboration of Jewel, Sarah McLachlan and the Indigo Girls. I’ve always been partial to James Taylor’s version, which concludes his highly regarded 1991 LP “New Moon Shine.”

“Cool Water,” Joni Mitchell with Willie Nelson, 1988

Bob Nolan, a respected singer/songwriter of Western music and actor in Western movies, wrote “Cool Water” in 1936, and it now ranks #3 on Western Writers of America’s list of 100 Greatest Western songs of all time. It tells the tragic tale of a parched man and his dying mule on a trek across a wasteland in search of water: “Come the dawn, we carry on, /We won’t last long without water, cool clear water… /Old Dan and I, our throats slate dry, /Our spirits cry out for water, cool clear water…” Nolan first recorded it as a member of Sons of The Pioneers with future singing movie star Roy Rogers, and a 1948 record with a different Sons lineup peaked at #4. Joni Mitchell invited Willie Nelson to join her on a sublime revival of the song for her 1988 LP, “Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm.”

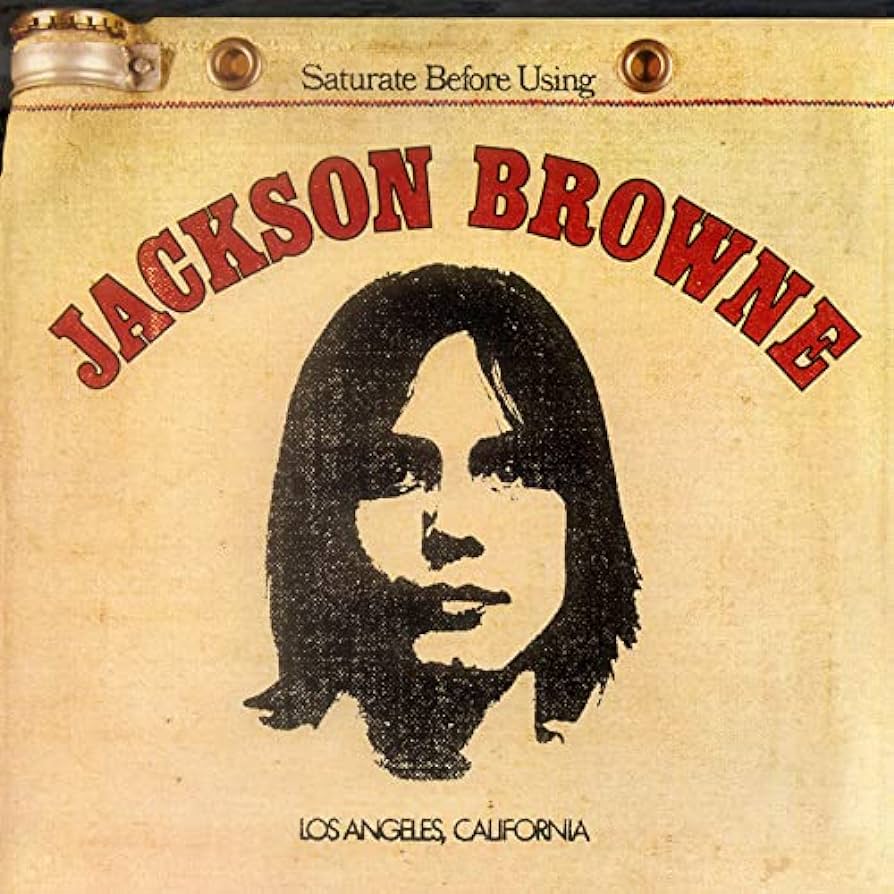

“Rock Me on the Water,” Jackson Browne, 1972

Browne has said, “It’s meant to be kind of a gospel song, using this gospel language: ‘stand before the father,’ ‘sisters of the sun.’ But it’s turning that around 180 degrees so it’s not about religion, it’s about society.” The lyrics are clear: “Oh people, look around you, the signs are everywhere, /You’ve left it for somebody other than you to be the one to care… /Rock me on the water, /sister, won’t you soothe my fevered brow…” Browne wrote it in the tumultuous political year of 1970, and it ultimately appeared on his 1972 debut LP and as his second single, peaking at #48, following the Top Ten hit “Doctor My Eyes.” Johnny Rivers, Brewer & Shipley and Linda Ronstadt loved the song and recorded it during the same period and, much later, Keb’ Mo’ did it justice on a “Songs of Jackson Browne” tribute album in 2014.

************************

Honorable mentions:

“Don’t Drink the Water,” Dave Matthews Band, 1999; “Something in the Water,” Pokey LaFarge, 2015; “Cool Cool Water,” The Beach Boys, 1970; “Gimme Some Water,” Eddie Money, 1978; “Washing of the Water,” Peter Gabriel, 1992; “Water Woman,” Spirit, 1968; “Oily Water,” Blur, 1993; “Deeper Water,” Paul Kelly, 2010; “Cool Water,” Joy Askew, 1996; “Something in the Water (Does Not Compute),” Prince, 1982; “Head Above Water,” Avril Lavigne, 2019; “Down By the Water,” The Decemberists, 2011; “Water,” The Who, 1970.

**************************