Makin’ love was just for fun, those days are gone

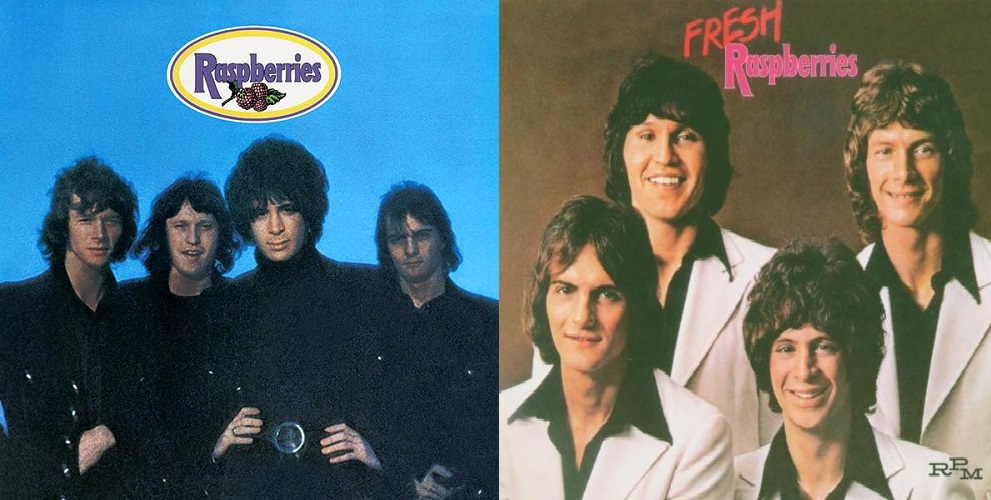

In the summer of 1972, a song started getting airplay that grabbed my attention. It had strong power chords like The Who, a vocal chorus like The Beach Boys, and lyrics that boldly talked about “going all the way.” As a teenager growing up in Cleveland, I was jazzed to discover the tune was by a local group called The Raspberries, who had been playing gigs at area high schools and teen clubs since 1970.

“Go All the Way” reached #5 on the national pop chart in October, followed by a second big hit, “I Wanna Be With You,” within a month or two. Despite these Top Ten successes, some critics and hipster album buyers turned their noses up at the group, calling them “wimpy Beatles imitators,” which hurt their momentum and reputation at a time when more complex music by progressive rock bands was in vogue.

Too bad. The band cranked out four LPs and managed one more Top 20 hit before frustration and internal dissension caused them to throw in the towel. Today, The Raspberries are praised as one of the pioneers of the “power pop” sub-genre that inspired many dozens of groups in the years since, from The Cars and Squeeze to The Bangles and The Posies.

The group’s lead singer and chief songwriter, who embarked on a solo career in 1975 and enjoyed worldwide fame for a half-dozen popular singles over the next 15 years, was Eric Carmen, who passed away this past week at age 74.

Although he is more broadly known as a balladeer for his solo work — particularly the 1975 power ballad “All By Myself” and his #3 hit from the 1987 “Dirty Dancing” film soundtrack, “Hungry Eyes” — I want to focus first on what Carmen was trying to do with The Raspberries.

Artists like Badfinger (“No Matter What,” “Baby Blue”) and Todd Rundgren (“We Gotta Get You a Woman,” “Couldn’t I Just Tell You”) and even early songs by The Who (“Substitute,” “I Can’t Explain”) exemplified the power pop sound, but many industry insiders have cited The Raspberries as the quintessential power pop band. “They are THE great underrated power pop masters,” Bruce Springsteen wrote in 2007. “Their best records sound as fun and as fresh today as when they were released. Soaring choruses, Beach Boys harmonies over crunchy Who guitars, lyrics simultaneously innocent and lascivious — that’s an unbeatable combination.”

Referring to “Go All the Way,” Carmen once said, “I wanted to write an explicitly sexual lyric that the kids would instantly get but the powers that be couldn’t pin me down for. So I turned it around so that the girl is encouraging the guy to go all the way, rather than the stereotypical thing of the guy trying to make the girl have sex with him. I figured that made us seem a little more innocent. We decided, ‘Let’s start it out like The Who, but when we get to the questionable part, we’ll do it like choir boys and maybe they’ll let it slide.”

Carmen had shown musical talent early, taking violin lessons from an aunt who played in The Cleveland Orchestra, and also learned piano and dreamed of writing songs. In high school, he was the lead singer in a series of bands, playing piano and guitar. While attending nearby John Carroll University, he cut one record (“Get the Message”) with a group called Cyrus Erie, which included guitarist Wally Bryson, who joined him in forming The Raspberries. Capitol Records signed them to a four-album deal.

“We got noticed by going completely against the grain in 1972,” Carmen said years later. “Prog rock and glam rock were ‘in,’ and FM radio embraced it, but I hated it. I loved the Beatles, The Who, the Byrds, the Stones, the Beach Boys and the Small Faces. Most of their songs were instantly appealing.”

I can’t fail to mention the gimmick employed upon release of their “Raspberries” debut album: The shrink wrap was adorned with a scratch-and-sniff sticker that smelled strongly of raspberries. The sticker must’ve been drenched in some potent concoction, because my copy of the album STILL has a faint raspberry aroma more than 50 years later!

The Raspberries’ catalog had great hook-filled power pop tunes like “Let’s Pretend” and “Tonight,” but sprinkled in there were mellower ballads like “Don’t Want to Say Goodbye” and “I Saw the Light,” dominated more by piano and string arrangements that recalled Paul McCartney’s oeuvre. That, apparently, was part of the problem, Carmen said.

“There were a lot of people in 1972 who were not ready for any band that even remotely resembled the Beatles,” he noted. “Critics liked us, girls liked us, but I guess their 18-year-old, album-buying brothers said ‘no.’ We got pretty frustrated, and things got a little intense.”

Two members of The Raspberries, drummer Jim Bonfanti and bassist Dave Smalley, left the group in 1974 and were replaced by Michael McBride and Scott McCarl, respectively, for their fourth and (as it turned out) final LP, “Starting Over.” Ironically, due to its harder rocking leanings (check out the Who-like “I Don’t Know What I Want”), Rolling Stone picked it as the best rock album of the year, but it flopped on the charts despite its superb single, the hopeful “Overnight Sensation (Hit Record).” Bryson’s tune, “Party’s Over,” chronicled his disillusionment with the music business: “When we started, it was a lot of fun, and the times we had I’ll never forget, /But now I’m older and wiser and a bit of a miser, and it’s crazy, but I don’t want to quit, /Ain’t it a shame, the party’s over…”

It’s telling that the song “Starting Over,” a piano-driven ballad, gave strong hints about the direction Carmen’s solo career would take when he released his “Eric Carmen” debut LP on Arista Records in late 1975. While there were several irresistible pop tracks that would have fit comfortably on any Raspberries album, the massively successful “All By Myself” (which I liked but grew sick of through overexposure) was often described as maudlin and overly sentimental. The fact that it was derived from a piano concerto by Sergei Rachmaninoff, covered by Frank Sinatra and later became a hit for Celine Dion indicates the kind of non-rock audiences that enthusiastically welcomed it.

The rest of the debut LP, though, is consistently strong and gorgeously produced by Jimmy Ienner, who had manned the boards for all four Raspberries albums as well. Great stuff here: the effervescent opener “Sunrise,” the Top 20 hit “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again,” the Brian Wilson-ish “My Girl” (no relation to the Temptations hit) and the dynamic cover of the ’60s chestnut “On Broadway.” Teen idol Shaun Cassidy had a big hit covering the album track “That’s Rock and Roll” two years later, and the hard-rocking “No Hard Feelings” did a nice job of summarizing the end of The Raspberries: “Four years on, and things were really gettin’ too intense, /Critics raving ’bout our album, but we’re makin’ fifty cents, /We gave it everything we had to give, but it was gettin’ so tough, /Too much frustration makes it hard to live, I think enough is enough, /I hope there’s no hard feelings ’cause there isn’t anyone to blame…”

Carmen decided to up his game in 1977 with the more artful album “Boats Against the Current,” which didn’t do as well commercially but sported more sophisticated songwriting on tracks like “Nowhere to Hide” (featuring The Guess Who’s Burton Cummings sharing vocals), “Marathon Man” and the title song.

His career arc took a dip when his three subsequent LPs in 1978 (“Change of Heart”), 1980 (“Tonight You’re Mine”) and 1984 (another LP entitled “Eric Carmen”) flopped on the album charts, although he managed two Top 40 chart appearances for the somewhat slight “Change of Heart” and “I Wanna Hear It From Your Lips,” which sounded suspiciously close to Springsteen’s lost classic “Fire.”

Interestingly, his next move was to collaborate with lyricist Dean Pitchford to write “Almost Paradise,” which became a #7 hit from the 1984 “Footloose” film soundtrack as sung in a duet by Loverboy’s Mike Reno and Heart’s Ann Wilson. That project led rather seamlessly to two more major successes for Carmen as a recording artist: The 1987 hit “Hungry Eyes” from the “Dirty Dancing” soundtrack, which peaked at #4, followed by another co-write in 1988 with Pitchford, the #3 smash “Make Me Lose Control.”

Those hits proved lucrative enough for him to back away from the business in 1990, abandoning the Los Angeles scene to return to his roots in Cleveland, where he spent most of the past 30 years laying low with his family in his high-end digs in Gates Mills.

Although his American audience proved rather fickle, running hot and cold in turn, Carmen was as surprised as anyone when he developed a rabid following in Japan, where crowds greeted him in Beatlemania-type frenzy. In 1982, I interviewed Carmen as he played host to a half-dozen Tokyo-based contest winners, who visited him in his Cleveland home, checked out some childhood landmarks and sat in on a mixing session in a local recording studio.

He was only sporadically active during recent decades. Carmen released one last LP in 1998, “Winter Dreams,” only in Japan, which included his own version of “Almost Paradise,” more co-writes with Pitchford, and cover versions of ’60s classics “Caroline, No” and “Walk Away Renee.” (The album was eventually released in the US as “I Was Born to Love You,” but it’s no longer available.)

In 2000, Carmen signed on for a stint in Ringo Starr’s All-Starr Band, performing 40 concerts with the likes of Dave Edmunds, Jack Bruce, Simon Kirke and, of course, Starr. Carmen was featured on “Hungry Eyes,” “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again,” “Go All the Way” and “All By Myself.” In 2014, as part of the release of “The Essential Eric Carmen” 2-CD compilation, he recorded and released his last new song, “Brand New Year.”

As for The Raspberries, any ill will between the members was eventually forgiven long enough for the group to reunite in 2004 for a well-received special show in Cleveland to commemorate the opening of the House of Blues location there, which precipitated another half-dozen shows at other House of Blues venues in 2005. The band’s legacy got another boost in 2014 when “Go All the Way” was used prominently on the “Guardians of the Galaxy” film soundtrack, exposing them to a whole new generation of fans.

Out of the small handful of rock musicians who have Cleveland connections, Carmen is a native who arguably achieved greater fame than anyone else on the list. (Joe Walsh lived in five other cities while growing up before attending nearby Kent State University and becoming a star in The James Gang; Chrissie Hynde is from Akron, not Cleveland; same goes for The Black Keys; Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails began his music career in Cleveland but grew up elsewhere; Benjamin Orr of The Cars and Neil Geraldo of Pat Benatar’s band grew up as proud Clevelanders and sold tons of records, but their names aren’t well-known outside rock music circles; artists like Tracy Chapman and Marc Cohn grew up in Cleveland but left early and haven’t had much nice to say about the city since leaving; and Michael Stanley, a Clevelander who was wildly popular there, isn’t all that well known elsewhere.)

In my view, The Raspberries (and probably Carmen as a solo artist) are every bit as deserving of induction in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as many bands that are already in there, but they’ve never even been nominated. It would be nice if Cleveland’s biggest rock star had his name on the wall.

Rest In Peace, Eric.

****************************