I know a change gonna come, yes it will

It’s been called one of rock and roll’s greatest mysteries.

It’s certainly one of its greatest tragedies.

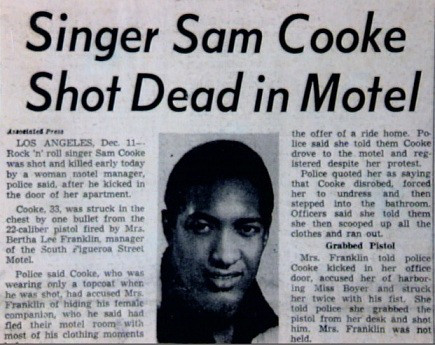

Sixty years ago this week, at a seedy motel in South Central Los Angeles, the popular and extraordinarily gifted singer Sam Cooke was shot to death, apparently by the motel manager, who claimed self-defense. Cooke was 33 years old.

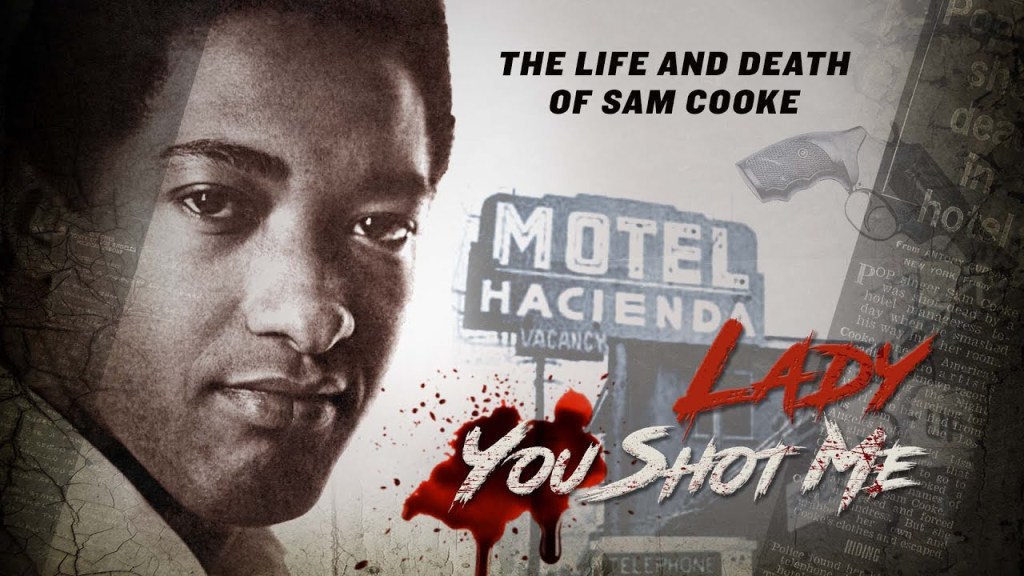

Friends, family members, journalists and attorneys have all publicly speculated in the years since that the slapdash police investigation, difficult-to-fathom circumstances and suspicious business relationships surrounding Cooke’s ignominious end all point to some sort of conspiracy. The 2017 documentary “Lady, You Shot Me: The Life and Death of Sam Cooke” examines the dubious nature of his violent death and concludes, in his nephew Eugene Jamison’s words, “It just doesn’t make sense.”

By 1964, Cooke had become the #1 black musical artist in the country, with an impressive run of more than 25 hit singles on the Billboard Top 40 pop charts, 20 of which were also Top Ten on the R&B charts. His first big single, “You Send Me,” reached #1 in 1957, and was followed by such classics as “Wonderful World,” “Chain Gang,””Cupid,” “Twistin’ the Night Away,” “Bring It On Home To Me,” “Havin’ A Party,” “Another Saturday Night” and “(Ain’t That) Good News,” among many others. He not only recorded these iconic tracks, he wrote them, published them and produced them in an era when black artists simply didn’t have that kind of clout.

From his early days as a gospel singer with The Soul Stirrers in the ’40s and early ’50s through his switch to secular musical styles in the late ’50s and early ’60s, Cooke was a keen observer of the music business. He had seen how artists, particularly black artists, had been cheated out of royalties and underpaid for live performances by unscrupulous managers, agents and record label moguls, and he was adamant that he wasn’t going to suffer that same fate. He founded his own publishing company, his own label and began amassing both wealth and power that upset the dynamic of the industry.

And yet Cooke still was taken advantage of by those he trusted — in particular, the notorious Allen Klein, who became involved in Cooke’s affairs in 1963 and engaged in shady dealings to wrest control of Cooke’s copyrights. (Klein infamously later mismanaged the finances of The Rolling Stones and The Beatles, who found themselves mired in lawsuits and countersuits with Klein for years on end.)

In a 2019 article in The Guardian by investigative reporter Ellen Jones, she wrote, “The week before (Cooke) died, he was planning to confront Klein over altered contracts and official documents. Could Cooke’s willingness to stand up to powerful vested interests have been a factor in his murder? Isn’t it time some enterprising filmmaker did a deep dive into Cooke’s death?”

In my view, “Lady You Shot Me” provides a pretty convincing case that the matter needs a thorough, official investigation, which had been continually obstructed by Klein before his own death in 2009 at age 77. When I watched the documentary last week on Amazon Prime, I grew angrier by the minute as the facts and informed opinions were presented. I urge my readers to make up their minds by watching the piece themselves, but I daresay you’ll draw the same outraged conclusion I did.

Cooke’s Wikipedia entry calls him “one of the greatest singers and most accomplished vocalists of all time. His incredibly pure tenor voice was big, velvety and expansive, with an instantly recognizable tone. Cooke’s pitch was remarkable, and his manner of singing was effortlessly soulful.”

Major stars of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s — iconic names like Otis Redding, James Brown, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Paul McCartney, Tina Turner, Steve Perry, Rod Stewart, Al Green, Mick Jagger and Diana Ross — have each praised Cooke as “hugely influential” in the development of their own singing styles.

As a student of rock music of the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, I’m sheepish to admit that I was late to the party when it comes to Sam Cooke. I was too young to have known about him while he was still alive (I was only nine when he died), but I didn’t even become aware of his name until the early ’80s. I recall seeing a cheesy TV commercial in the late ’70s advertising a bargain “greatest hits” collection by “the legendary Sam Cooke” and thinking, “Who?? How can he be legendary if I’ve never heard of him?”

When my friend Gary played his records one night in 1985, I fell in love with the songs and, especially, the voice. Sure, I’d heard “You Send Me” before, and I recognized “Twistin’ the Night Away” from its use in the “Animal House” film soundtrack. But I was kicking myself for not having fully appreciated this guy before. I picked up two outstanding CD compilations — the 28-song “The Man and His Music” (1986) and the grittier blues collection “The Rhythm and The Blues” (1995) — and found that the deeper I dove into his recorded catalog, the more I was dazzled by his expressive tenor and the way he could successfully handle such a wide range of genres.

He could wrap his voice around a time-honored gospel song like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and then pick up Nat King Cole’s mantle as a convincing crooner of standards like “Mona Lisa.” Cooke’s mastery of legendary blues tunes like “Nobody Loves You When You’re Down and Out” is every bit as impressive as his take on a pop confection like “Cupid.” These days, whenever a Cooke track comes up on somebody’s playlist, I stop what I’m doing and just marvel at that voice.

Cooke began singing in Chicago at age six in the children’s choir of the Baptist church where his father was preacher. He started getting noticed when he became the lead singer with the gospel vocal group The Highway Q.C.s at the tender age of 14. He received wider exposure when, at 18, he took over R.H. Harris’s place as lead tenor in The Soul Stirrers, who were signed with Specialty Records, where they recorded such gospel standards as “Jesus Gave Me Water,” “Touch the Hem of His Garment” and “Peace In the Valley.”

While gospel was popular, Cooke recognized that its fans were mostly limited to rural communities, and he wanted to expand his reach by attempting other genres, notably pop and soul music. Where artists like Marvin Gaye faced heated opposition from his preacher father for abandoning religious music for secular music, Cooke was surprised and pleased that his father supported his son’s career move. Said Cooke, “My father told me it was not what I sang that was important, but that God gave me a voice and musical talent, and the true use of His gift was to share it and make people happy.”

He covered classics like George Gershwin’s “Summertime” and The Ink Spots standard “(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons,” but noting that the real money in the music business went to the composers who held the copyrights, Cooke began writing songs, and eventually, most of the hits he recorded and released were Cooke originals. He focused on singles and built a solid legacy on those charts, but he also enjoyed a couple of high-rated albums as well — 1963’s blues-oriented “Night Beat” (which reached #62) and 1964’s “Ain’t That Good News,” which included three hit singles and peaked at #34.

Cooke was also intensely interested in the growing civil rights movement in the early ’60s. He became friends with Martin Luther King and the more revolutionary Malcolm X, as well as sports giants Jim Brown and Cassius Clay (later Muhammad Ali). The award-winning stage play and film “One Night In Miami” offers a fictionalized account of the night Cooke, Brown and Malcolm X were all together to see Clay’s upset of heavyweight boxing champ Sonny Liston, and their meeting to discuss how they could help advance the civil rights cause.

In the film, the outspoken Malcolm accuses Cooke of disloyalty to the black community by pandering to white audiences, and Cooke calmly argues that his method produces greater economic empowerment for black artists. Malcolm harshly ridicules the music Cooke has produced since finding success, but Cooke insists his success and creative autonomy is itself an inspiration to the black community. He agrees with Malcolm that Bob Dylan’s then-new “Blowin’ in the Wind” showed that protest songs with thought-provoking lyrics could become popular on the charts, and points to his own profoundly relevant “A Change is Gonna Come” as indicative of the kind of songs he’d be writing in the future.

Sadly, that landmark track wasn’t released as a single until after his death, which ironically gave it even more impact in 1965 as the watershed Voting Rights Act was passed and the movement took center stage in communities across the country. In the 2017 documentary, it was pointed out that Barack Obama quoted from the song often during his 2008 Presidential campaign speeches, which helped revive Cooke’s name and reputation as an iconic cultural figure.

I’ve chosen not to devote too much space here to all the details and conjecture surrounding his shocking death. The documentary does a thorough job of that, and I’ve always preferred to write about the music and achievements of artists like Cooke rather than their ignoble demises. As his nephew said, “My uncle’s star shone very brightly for a short period of time. Some stars are tragic figures. Sam Cooke was not a tragic figure. He was a very good person who just had a tragic ending.”

Bill Gardner, the longtime radio host of the “Rhapsody in Black” program on KPFK-FM in Los Angeles, said, “Sam was never a violent guy. I never saw him get angry. Never saw him want to hit anybody. Hard for me to believe the story as it appears in the police report. In my opinion, everyone should be a suspect, but I don’t think we’ll ever get to the bottom of it.”

As a musical coda to Cooke’s story, the impactful singers Dion DiMucci and Paul Simon teamed up in 2020 to write and record the poignant “Song For Sam Cooke (Here in America),” with provocative lyrics that remind us that the struggle still goes on: “You were a star when you were standing on a stage, /I look back on it, I feel a burning rage, /You sang ‘You Send Me,’ I sang ‘I Wonder Why,’ /I still wonder, you were way too young to die, /Here in America…” I’ve included the track as the final entry on my Spotify playlist below.

It’s profoundly sad to acknowledge how we were all robbed of the chance to hear more from this wondrous singer, and to imagine what Sam Cooke might have accomplished in the ensuing decades.

**************************