Tell me why you’re crying, my son

In 1968-69, I was learning how to play guitar as a middle schooler. The songs my friend Ben Beard and I chose to learn and memorize were acoustic guitar-based with tight harmonies: a lot of Simon and Garfunkel, some Beatles and several by Peter, Paul and Mary.

We were especially fond of three songs PP&M played: the old spiritual “If I Had My Way,” their #1 hit written by John Denver, “Leaving On a Jet Plane,” and especially Peter Yarrow‘s rousing antiwar anthem “Day Is Done,” with its lyrics that balanced angst with hope: “Do you ask why I’m sighing, my son? You shall inherit what mankind has done, /In a world filled with sorrow and woe, if you ask me why this is so, I really don’t know, /And if you take my hand, my son, all will be well when the day is done…”

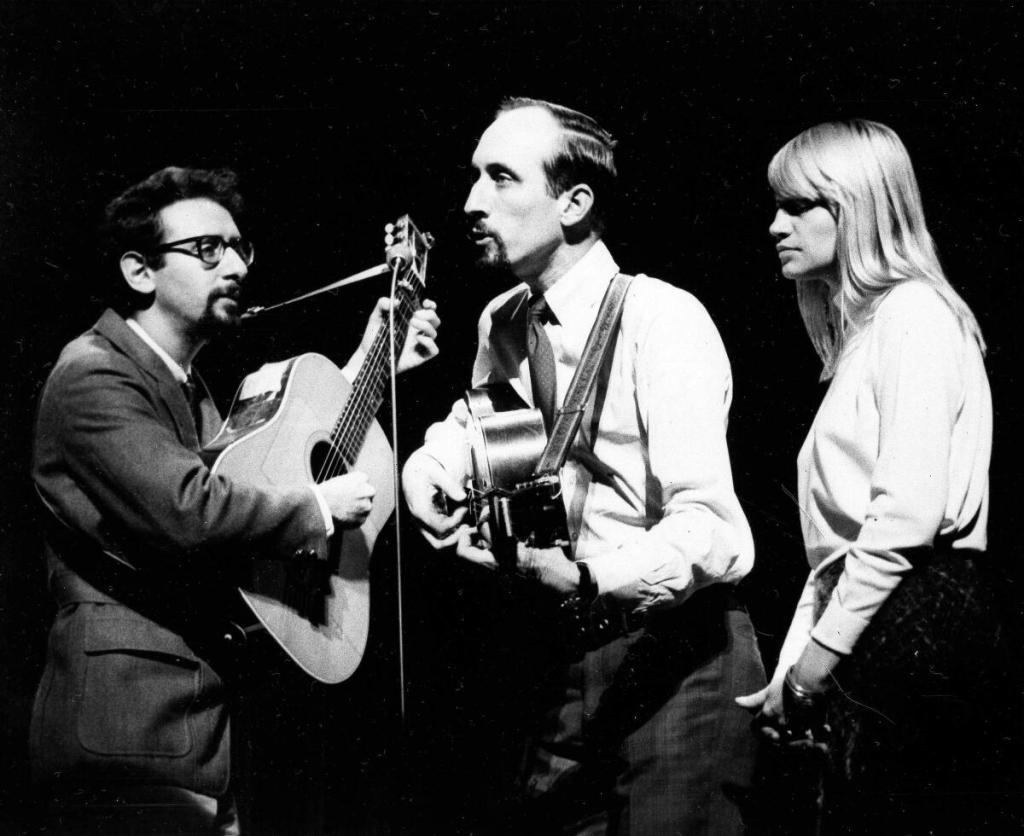

So the news that Yarrow had died of cancer January 6th at age 86 tugged a bit at my heartstrings. Although the righteous folk music that was PP&M’s specialty had largely fallen out of favor in the late ’60s as rock music took over, I always thought highly of their marvelous voices and strong passion for the noble causes of peace and civil rights, and counted the trio among my early influences.

Yarrow, Paul Stookey and Mary Travers first joined forces in Greenwich Village in 1961 amid a thriving folk music club scene there, populated by the likes of Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and a then-unknown Bob Dylan. Indeed, it was Dylan’s then-manager Albert Grossman who saw their individual talents and commercial appeal and brought the three artists together. They hit a home run right out of the box with their self-titled Grammy-winning debut LP, which reached #1 and included folk standards like “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” “500 Miles,” “Lemon Tree” and “If I Had a Hammer.”

Yarrow recalled in 2009, “I had a very strong sense of purpose at that time. Mary never believed this would go much further than a year or so. Paul also was doing it on a temporary basis. But I had a different concept. Our voices, singing the way we were singing … I felt that we were carrying on a tradition that would be very important in terms of what was happening in the world. I really felt that we had something important to share.”

Some conservative factions in those days saw subversive meanings in popular music lyrics where none existed, and one of the first to face such criticism was Yarrow’s children’s tale, “Puff the Magic Dragon.” Ludicrously called out for being all about illicit marijuana use, “Puff” was nonetheless an enormous hit, reaching #2 in the US and a Top Five entry in four other countries. Yarrow always maintained that the song “never had any meaning other than the obvious one — the loss of innocence in children, and the hardships of growing older.” It went on to inspire three animated TV specials in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and a book adaptation.

Partly due to Grossman’s influence, Peter, Paul & Mary recorded and had huge chart success with original songs by Dylan, most notably “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” The trio famously performed the former song at the legendary March on Washington in 1963 when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, and the lyric’s focus on questions about peace, war and freedom pushed it, and PP&M, to the forefront of the civil rights movement.

“It was so incredibly powerful, that moment,” Yarrow said years later. “Washington was a segregated city at that time. Here we were in our nation’s capitol, where we proclaimed with others that there was liberty and justice for all, and yet there still separate drinking fountains for blacks and whites. Mary later told me, ‘Do you remember when we were standing there listening to the speech? I took your hand, and I said, ‘Peter, we are watching history being made.””

The trio, and especially Yarrow, took on leadership roles as activists and as musicians, joining the board of the Newport Folk Festival, organizing the 1969 March on Washington and pushing for liberal candidates and causes for decades afterwards, including Barack Obama’s presidency and the National Hospice Movement and the Operation Respect anti-bullying campaign.

But Yarrow was apparently a complicated man, and it pains me to have to write about a dark chapter in his life when, in 1970, he was convicted of “immoral and improper liberties” with a teenage girl and spent three months in prison for it. He said years later, “It was an era of real indiscretion and mistakes by many male performers, and I was one of them. I got nailed for it, I was wrong, and I’m sorry for it.” In recent years, his ability to publicly support candidates and causes was curtailed by rekindled attention on his regrettable behavior.

I don’t recall hearing much about the matter in 1970 as I was playing his albums and learning his songs, but being reminded of it in obituaries last week forced me to come to terms with Yarrow as a flawed man whose unforgivable actions conflicted mightily with his support for humanitarian concerns.

Still, I continue to admire his body of musical work. Yarrow was instrumental in devising the vocal arrangements that made the best use of Stookey’s baritone, Travers’s contralto and his own tenor, combined in soothing harmony on nine albums during their initial 1962-1970 run. Almost as important, his and Stookey’s deft acoustic guitar playing lifted their material above the majority of folk-based musical offerings of that era.

Yarrow wasn’t a prolific songwriter, but the philosophical wisdom and loping melody of his 1967 song “The Great Mandella (The Wheel of Life)” stands, in my view, as one of his best moments. I also recommend checking out his sadly ignored solo debut LP — now available as one third of a trio of the solo albums “Peter” (1972), “Paul And” (1971) and “Mary” (1971). On Yarrow’s record, you’ll find several tracks worthy of your attention such as “Mary Beth,” a lovely ballad to his wife, the spiritually centered “River of Jordan” and the hopeful singalong “Weave Me the Sunshine.”

Stookey ended up scoring the biggest chart success of the three solo careers with “Wedding Song (There is Love),” a ceremonial ballad he wrote on 12-string guitar and performed for Yarrow’s wedding in 1971, which peaked at #24 on the US Top 40 chart.

Here’s something I never knew about Yarrow: He co-wrote and co-produced “Torn Between Two Lovers,” the hit single about a romantic love triangle that managed to reach #1 on US pop charts for Mary MacGregor in early 1977.

Peter, Paul and Mary reconvened in 1978 for the aptly titled “Reunion” LP, and they went on to release four more albums between 1986 and 2003, but they barely made a dent in the charts. Their time, evidently, had come and gone, although their occasional concerts during those years drew appreciative audiences of older, faithful fans.

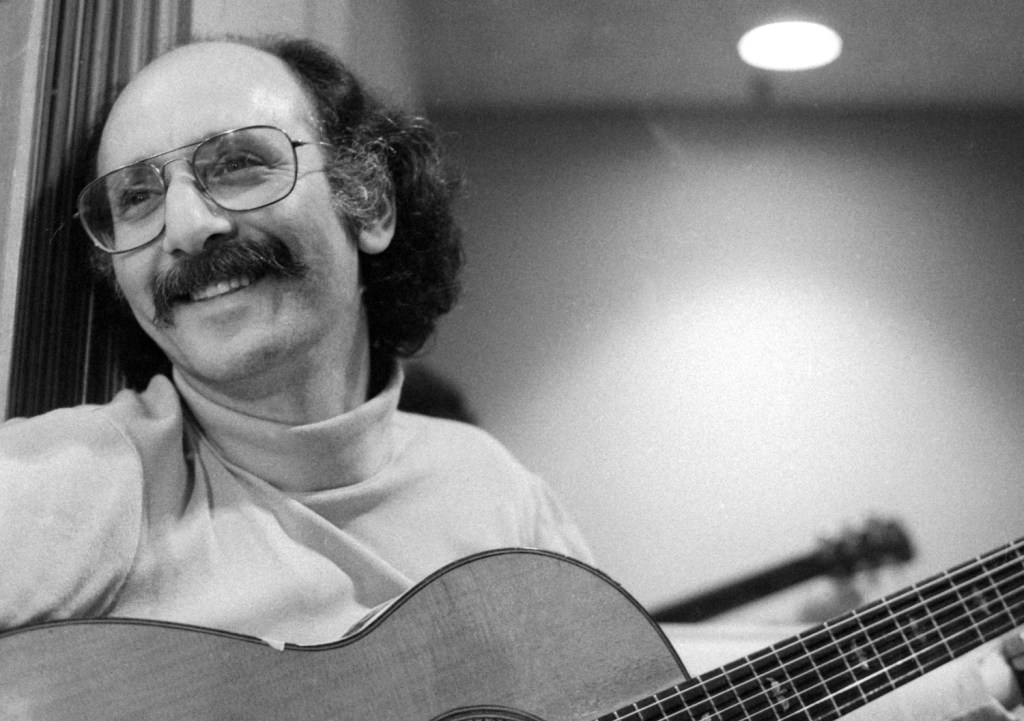

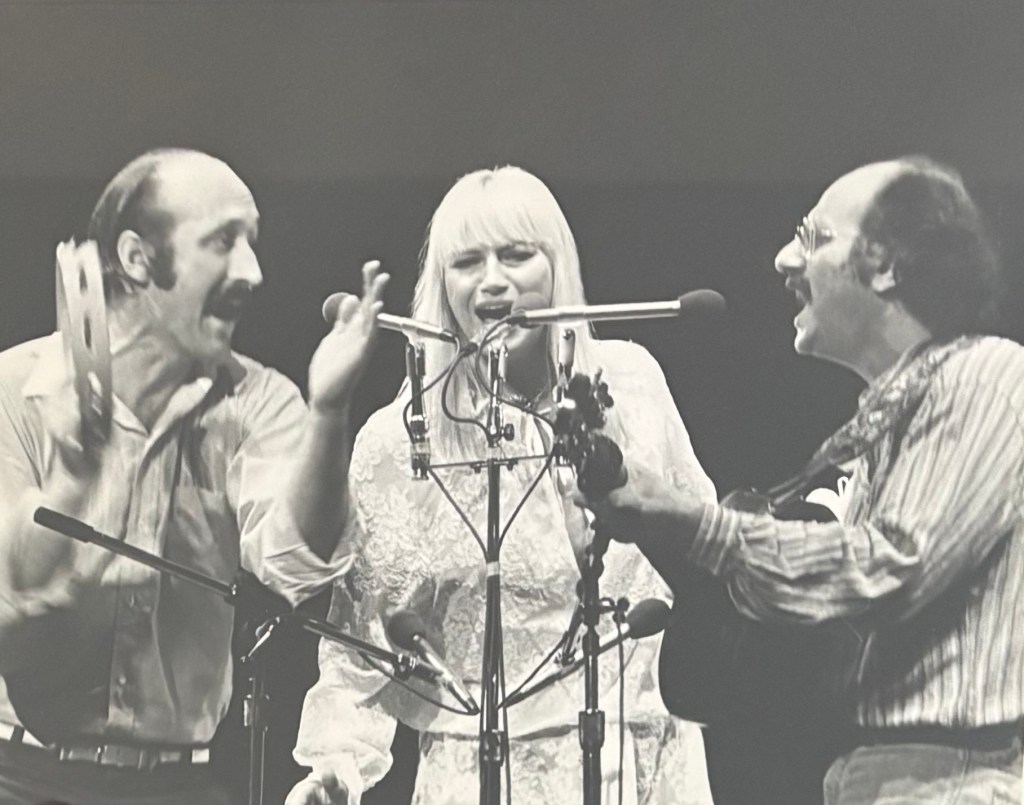

In 1981, as a newspaper concert critic in Cleveland, I had the opportunity to interview them backstage, take some performance photos and write a justifiably favorable review (see photos above and below). In that interview, Yarrow told me how they would select their repertoire. “For us to sing a song, not only does it have to have an engaging melody, but the words need to have a sense of truth. They can’t advocate a philosophy we don’t believe in. They should be somewhat constructive. They can be angry but not hopeless. In short, they have to move us.”

In addition to the anthems of commitment and concern, they sang tender ballads (Gordon Lightfoot’s “Early Morning Rain,” Yarrow’s “Moments of Soft Persuasion”), rousing pop tunes (“Rollin’ Home,” “I Dig Rock and Roll Music”), holiday madrigals (“A-Soalin'”) and whimsical ditties like “I’m in Love With a Big Blue Frog,” a parody of “Ghost Riders in the Sky” called “Yuppies in the Sky,” and an anti-racist screed called “Listen Mr. Bigot.” They even did “Peter, Paul & Mommy,” a whole album of children’s songs.

On another more personal note, I shall be forever indebted to Yarrow for discovering and signing a trio of musicians known as Lazarus in 1970. Their stunning harmonies and original songs by guitarist Billie Hughes made an indelible mark on me, and on a number of friends with whom I shared their two albums. On the first LP’s liner notes, Yarrow wrote, “A thousand talented kids had spoken to me after concerts, asking me to hear their tunes. Why had I not just offered them an address to send their tape? Then I heard their music, and it was all clear to me the role I would play in their lives. Their songs just made me feel so good.” Although they toured behind Yarrow and other acoustic acts of that period, they never caught on, which is a huge shame. (I’ve included two of their songs on the Spotify playlist below to give you a taste. The members of Lazarus also sang harmonies on Yarrow’s solo track “Take Off Your Mask.”)

R.I.P., Mr. Yarrow. Thanks for your musical contributions, and I hope you find some measure of peace in your next life.

********************************