It took me years to write, will you take a look?

Everyone has a story to tell.

For those famous enough to get a publishing deal, writing one’s memoirs seems to be more popular than ever. In the world of pop music, especially rock music of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, writing an autobiography, it seems, has become the latest rite of passage for many who thrived in that era.

Readers who know me well are aware that, when it comes to books about rock music, I inhale them. Reference books about the Billboard charts, in-depth examinations of specific genres or regions, biographies (authorized and unauthorized) of famous artists and producers — I love ’em all, soaking up interesting factoids and arcane album information for use in some future party conversation (or this blog).

But why the spike in rock ‘n roll memoirs from survivors of rock’s earlier decades? Call me cynical, but I’m guessing many of these aging performing artists figure they better commit their tales to paper ASAP before their memories fail them or they keel over (God knows that’s been happening way too often lately).

These memoirs typically include at least one “tell-all” bombshell that will help sell copies, but the best ones offer truly insightful information and thoughtful opinions from some of the major (and minor) players in the rock music kingdom. And if the reader is really lucky, the book might actually be well written.

Sadly, the bookshelves are littered with recent examples of what amount to “Dear Diary” ramblings — self-indulgent, immature, lamely crafted and in dire need of major editing or a total rewrite. But the good news is they’re outnumbered by a few dozen really captivating memoirs written in intelligent prose, with a healthy mix of humor, humility, pathos, perspective and (you can’t avoid it in this business) ego.

Let’s face it, if you’re a popular music artist, let alone a rock and roll star, it’s assumed you likely have an outsized ego, an ego big enough to tell you your life is interesting enough, and important enough, that people are going to want to read all about it, from childhood through early struggles to fame and fortune, to maybe scandal, setbacks and rehab. How literately you tell your story, it should be noted, makes all the difference between respect and ridicule in the end.

Speaking of ridiculous, these days we have young artists writing their memoirs who have barely turned 30. I mean, Justin Bieber? It’s laughable. Best to wait until you’ve had a life long enough to write about.

No one can say for sure if some of these “autobiographies” were helped along by seasoned journalists serving as ghost writers, but I’m going to give the stars the benefit of the doubt and trust them if they said they wrote them themselves. All I know is, if it’s an entertaining read, and I learn things I didn’t know before, and I’d recommend it to others, then it was worth my time and money.

Here are 20 rock ‘n’ roll memoirs I found to be worthy of your attention. These are not biographies written by others, only autobiographies. Full confession: I didn’t read ALL of EVERY book listed here. In a few cases, I only skimmed them in preparation for this blog, and read a summary of reviews. But my aim is to read them all someday.

******************************

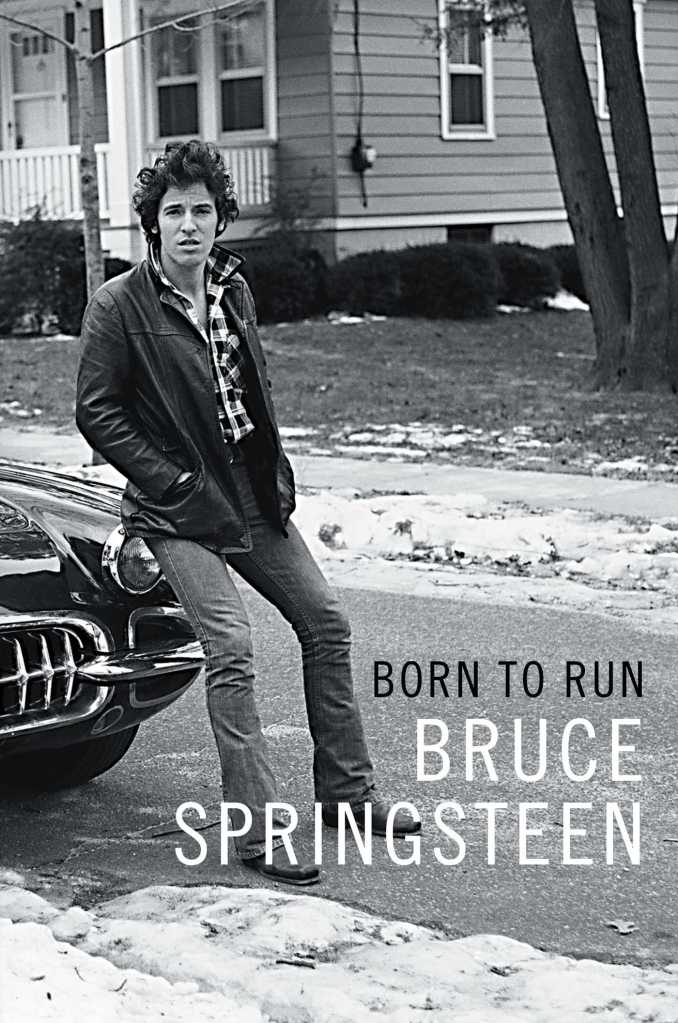

“Born to Run,” Bruce Springsteen, 2016

As a lyricist, Springsteen has written pungent, heartfelt lyrics both concise and wordy, capturing moments and emotions better than almost anyone. To no one’s surprise, The Boss writes lucidly and with great precision in his memoirs about his long, slow journey from the dead-end Jersey Shore to the peaks of superstardom. Despite the fact that he’s added another ten years of achievements since this book was first published, this book is a satisfyingly comprehensive look at one of rock’s finest composers and showmen.

“My Cross to Bear,” Gregg Allman, 2012

I’m not sure I should have expected anything else, but Allman’s book revealed him to be an incredibly selfish asshole for much of his life, and he admits as much. There’s no denying his brilliance as a blues singer, keyboardist and songwriter, but holy smokes, he was horrible to every woman in his life, and self-destructive as hell. Still, he writes about all this in candid, compelling fashion, and got it done five years before his death in 2017 at age 69.

“Boys in the Trees: A Memoir,” Carly Simon, 2016

Largely at arm’s length from the self-destructive lifestyle that damaged many of her contemporaries, Simon survived to tell a decidedly different story from most ’70s singer-songwriters. She writes from a calm epicenter as a daughter/mother/wife more than as a Grammy-winning artist, and it’s not at all boring but, in fact, invigorating. I just read this one within the last year and don’t know why I put it off for so long. She has a fascinating story to tell.

“Not Dead Yet: The Memoir,” Phil Collins, 2016

What a treat! The fact that Collins tells his long and winding story with such self-deprecating charm and humor lays waste to his unfair reputation as an egotistical jackass. He even uses his book’s title to debunk the silly “Phil is dead” rumor that plagued him in the mid-2000s. His evolution from Genesis’s replacement drummer in 1970 to their new lead singer in 1976 to ubiquitous solo artist in the 1980s and back into the band’s final years in the 2000s is quite a tale. This might be the most entertaining read on this list.

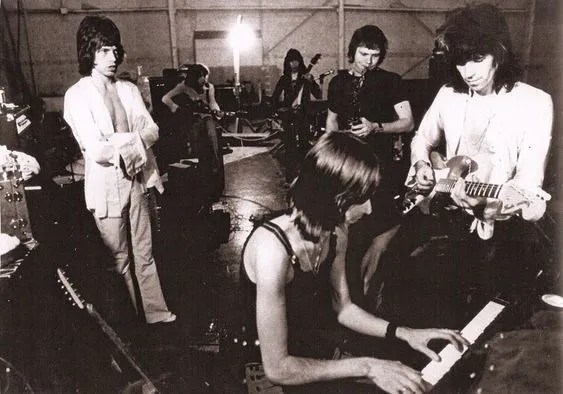

“Life,” Keith Richards, 2011

Given Keef’s notoriety as rock’s drug poster boy over the years, pretty much nobody expected this to be even remotely as great as it turned out to be. How could he remember much of anything, given all he’s ingested? But recall he did, with considerable flair, and the result is one of the most praised rock autobiographies ever. And he has lived on for another 15 years since it was published. Go figure.

“Simple Dreams: A Musical Memoir,” Linda Ronstadt, 2013

One of the most impressive singing careers of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s was cut short in heartbreaking fashion when, in 2011, Ronstadt was diagnosed with a degenerative disease which robbed her of, among other things, the ability to control her vocal cords. She turned her attention to writing “Simple Dreams,” a humbly philosophical memoir of her life, which included multiple hit albums and singles in the folk, country, rock, Big Band and Latino musical genres.

“Me,” Elton John, 2019

If you saw the “Rocketman” musical biopic released the same year, you may think you know all there is to know about the shy-boy-turned-superstar, but I assure you, you don’t. In “Me,” Elton John goes far deeper into his life and career, warts and all, offering his own candid observations on the early struggles, the fame, the conflicted sexuality, the excesses, the musical partnerships and his eventual rejuvenation as an elder statesman of rock.

“Long Train Runnin’: Our Story of The Doobie Brothers,” Tom Johnston and Pat Simmons, 2023

Here’s a novel approach to the autobiographical genre. As founders and primary songwriters, singers and guitarists of The Doobie Brothers, Johnston and Simmons collaborated on this memoir by taking turns telling their versions of the group’s compelling history in 26 chapters — before, during and after the arrival of Michael McDonald. It’s a delightful way to learn how little animosity there was between the various players as the band’s lineup shifted through the years.

“Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words,” as told to Malka Marom, 2014

In a different twist on autobiographical literature, Mitchell teamed up with long-time confidante/journalist Malka Marom on three occasions (1973, 1979, 2012) to do lengthy, detailed taped interviews, which have been transcribed in Q&A format, giving readers a great deal of insight into Mitchell’s creative process and her development as a consummate musician. It was published before her debilitating aneurysm in 2015, withdrawal from the public eye and subsequent revival since 2022, but that’s not the focus here anyway. If you love Joni, or the art of songwriting, this one is a must.

“Play On: Now, Then and Fleetwood Mac,” Mick Fleetwood, 2014

The drummer, founder and mainstay of Fleetwood Mac throughout its multi-colored history wrote an earlier memoir in 1991, and much of it is recapped here, but with substantial new sections covering the next 20 years. There hasn’t been too much new to the band’s story since then, so this is about as complete a story as you’ll find of Fleetwood Mac’s various phases (the Peter Green blues years, the Bob Welch-led middle years, and the soap-opera-ish years with Lindsay Buckingham and Stevie Nicks).

“Wild Tales: A Rock & Roll Life,” Graham Nash, 2013

Always the most level-headed of the raging egos in Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Nash writes thoughtfully and with panache, and a candor that’s almost eyebrow-raising at times. As a guy who broke into the business with The Hollies back in 1963 and is still active 62 years later, he has a million great anecdotes and stories to share about his songs, his relationships and his passions. Check it out.

“Rod: The Autobiography,” Rod Stewart, 2012

I am not much of a fan of Stewart, but he has played a huge role in rock music over his five-decade ride through rock’s headiest years, from obscure vocalist with the Jeff Beck Group in 1968 to interpreter of the Great American Songbook in the 2010s. Rod’s memoirs openly admit he was a lucky SOB, but the book also spends an inordinate amount of time on the tabloid-ish blonde-women-he-took-to-bed stuff instead of his musical contributions. Is it because the former outweighs the latter?

“Reckless: My Life as a Pretender,” Chrissie Hynde, 2015

This is one badass woman, thriving and surviving as a lady rocker at a time when it was almost exclusively men’s terrain. Her memoirs tell a sometimes harrowing story about growing up in hardscrabble Akron, Ohio, fleeing to London during the birth of punk, and emerging as a victorious pioneer of New Wave in the early ’80s. No doubt about it — Hynde has moxie.

“Delta Lady: A Memoir,” Rita Coolidge, 2016

My wife met Coolidge at an industry gathering several years ago and was captivated by her spirit, her guile and her still-impressive artistry. Many rock fans most likely have no clue how connected she was, professionally and personally, to so many pivotal people in the ’70s and ’80s, and consequently, her memoir makes for illuminating reading.

“Who I Am,” Pete Townshend, 2012

The leader of The Who tends to take himself quite seriously, perhaps too much so, and that makes his autobiography kind of exhausting to absorb. We’ve always known Townshend is a great writer, having contributed numerous cogent commentaries to Rolling Stone over the years, so the high quality of the narrative here comes as no surprise. He reveals with brutal candor pretty much all we’ll ever need to know about The Who’s stormy journey and his life in and out of the band.

“Clapton: The Autobiography,” Eric Clapton, 2007

A rock idol and guitarist extraordinaire, Clapton led a life full of difficulties, many of them self-inflicted, and his memoir spells it all out in wrenching detail, simultaneously exposing himself as a man who spent years mostly incapable of maintaining anything close to a healthy personal relationship. Too bad such a fine singer/songwriter and master interpreter of blues music suffered so much in his personal life…but they say that’s what makes the blues so authentic. Clapton has continued to record and perform in the 18 years since this memoir was published, but it will still give you a solid look at his career.

“It’s a Long Story: My Life,” Willie Nelson, 2015

His first memoirs were published in 1988, and since then his persona has only grown in stature and notoriety. Consider the title of his 2012 book, “Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die: Musings From the Road,” which pays perhaps too much attention to his pro-weed stance at the expense of his sizable impact on country (and pop) music over the last 40+ years. And he is STILL around adding to his legacy at age 92. This one is well worth your time, trust me.

“Sweet Judy Blue Eyes: My Life in Music,” by Judy Collins, 2011

Folk chanteuse Judy Collins took us all off guard when she used her memoir, “Sweet Judy Blue Eyes,” to confess a lifelong battle with alcoholism that tormented her personal relationships as well as her recording career. Her message: “You don’t have to be a rock and roller to have substance problems.” Hers is a fascinating story of a journey through the early folk years into the mid-’70s period of hedonistic pursuits that ultimately took their toll on her.

“Fortunate Son: My Life, My Music,” John Fogerty, 2015

The man who wrote, produced, arranged, sang and played guitars and keyboards on virtually every song Creedence Clearwater Revival ever recorded was also naive and too trusting when it came to business, and it had a profoundly negative impact on his life and career. Fogerty clearly never got over the betrayal of former manager Saul Zaentz, resulting in memoirs that spend far more space on accusations and recriminations than on the brilliant music that is his true legacy. Still, it’s an absorbing study of the highs and lows of one of America’s top bands of the 1968-1972 period.

“Chronicles, Volume One,” Bob Dylan, 2004

Always the mystery man, Dylan chose to focus this 300-page tome on only three disparate points in his lengthy career: 1961, as he released his debut album; 1970, around the time of “New Morning”; and 1989, the year of his “Oh Mercy” LP. Readers are left salivating for more, much more, but so far, he hasn’t followed through on his plans for Volume Two (or Three). It’s hard to criticize him for choosing to write, record and tour at age 84 instead of completing his memoirs, but I sure would love to read about the many chapters of his life he has thus far ignored.

*********************************

A few more titles you might want to explore:

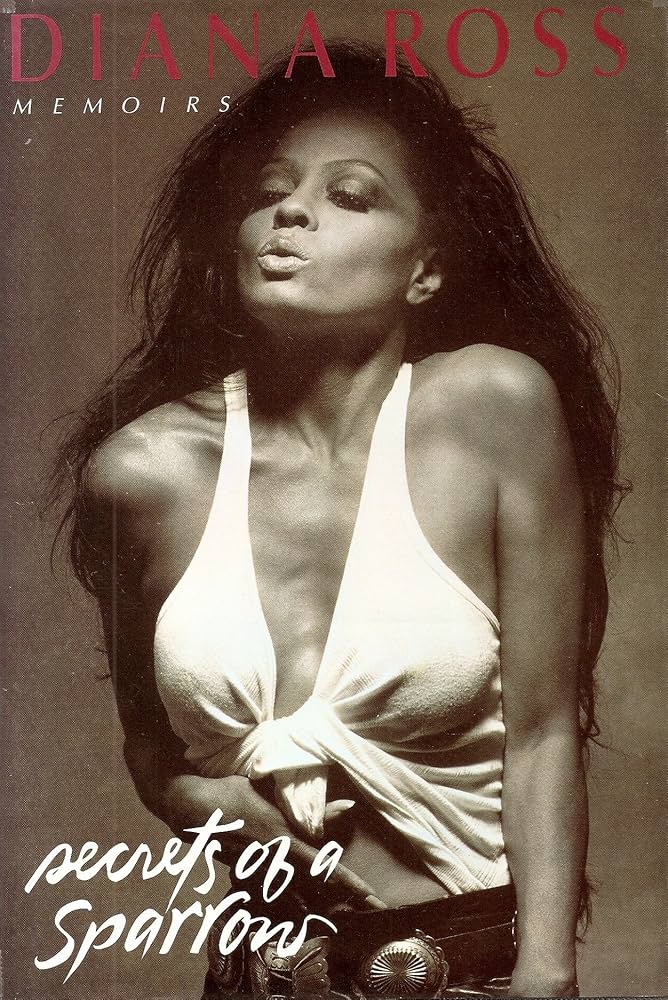

“Secrets of a Sparrow,” Diana Ross, 1993

“Cash,” Johnny Cash, 1997

“Long Time Gone: The Autobiography of David Crosby,” David Crosby, 1988

“I Me Mine,” George Harrison 1979/2017

“Heaven and Hell: My Life in the Eagles,” Don Felder, 2007

***************************

I can’t conclude this list without bashing a few titles that I found pretty much unreadable:

Aerosmith vocalist Steven Tyler appropriately titled his excruciating memoirs “Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?” (Answer: Damn right it does, Steve, when it consists of incoherent babblings, brash boasts and baffling non sequiturs.)

David Lee Roth of Van Halen evidently vomited his mindless ramblings into a tape recorder, had it transcribed, and slapped a title on it: “Crazy From the Heat.” (You’ve got that right, Dave…)