God only knows where we’d be without him

The more I have learned about the life of Brian Wilson, the more I have felt sorry for him.

Here was a man — an extraordinary talent bursting with innate creativity and imagination — who had to face unrealistic expectations, an abusive father, a fickle public, a manipulative therapist and a debilitating unease with his own mental health. He was the undisputed leader of The Beach Boys, the most commercially successful American rock band of the 1960s, but he was shy, emotionally vulnerable and not particularly good at defending himself and his methods against naysayers and backstabbers, even within his own family.

When we label someone a genius, it turns out to be a double-edged sword. Certainly, it’s a supreme compliment, for it identifies that person as one of the very best of us — unparalleled at their craft. Yet it also puts them and everything they do under a microscope and burdens them with enormous stress to maintain their excellence every day.

Wilson, who died on June 11 at age 82, met these challenges head on and produced some of the most sublime, brilliant, iconic music of our lifetimes…for a while. And then he couldn’t do it any longer, becoming erratic, isolated, full of self-doubt. Lesser men might have pulled the plug and “checked out,” but Wilson endured for decades after his initial unraveling, still showing occasional flashes of musical magnificence but no longer operating at his peak.

From 1962 through 1967, what a peak it was! He wrote or co-wrote a dozen Top Ten singles and another six dozen album tracks, handled all the vocal and instrumental arrangements, and oversaw the studio production of everything The Beach Boys recorded. Deeply inspired by the songwriting of George Gershwin and Burt Bacharach, the vocal harmonies of The Four Freshmen and the studio techniques of Phil Spector, Wilson broke new ground in the arena of popular song — its structure, its instrumentation, its use of ever-evolving studio technology. He was pretty much peerless, as many of his peers will readily tell us.

“Brian had that mysterious sense of musical genius that made his songs so achingly special,” Paul McCartney wrote on social media following Wilson’s death. “The notes he heard in his head and passed on to us were simple and brilliant at the same time. I feel privileged to have been around his bright shining light.”

John Sebastian of The Lovin’ Spoonful noted, “Brian had control of this vocal palette of which the rest of us had no idea. We had never paid attention to the Four Freshmen or doo-wop combos like The Crew Cuts. Look what gold he mined out of that.”

Peter Gabriel said, “What an extraordinary talent! Brian Wilson single-handedly raised the bar on how to write and arrange a great pop song. He inspired and touched so many songwriters, including me. His work pushed The Beatles towards ‘Sergeant Pepper’ and, in ‘God Only Knows,’ he created a masterpiece that remains unmatched to this day.”

Elton John had this to say: “For me, he was the biggest influence on my songwriting ever. He was a musical genius and revolutionary. He changed the goalposts when it came to writing songs and shaped music forever. A true giant.”

**********************

Born in 1942 in Inglewood, California and raised with his two brothers Carl and Dennis in nearby Hawthorne, another Los Angeles suburb, Brian Wilson showed an innate musical talent even as a toddler. His father Murry, a machinist who fancied himself a frustrated songwriter, strongly encouraged Brian’s interest in music, financing accordion lessons and buying a piano on which Brian taught himself popular songs of the day. His church choir director declared him to have perfect pitch, and his high school music teacher marveled at Brian’s aptitude for learning everything from Bach and Beethoven to boogie-woogie and rhythm & blues.

Wilson often gathered his friends and brothers around the piano, teaching them the various vocal harmonies from songs by Dion and The Belmonts and others. His father also bought him a two-track tape recorder, which allowed him to experiment with recording songs, group vocals, and rudimentary production techniques at an early age. In an essay he wrote as a high school senior, Wilson said, “My ambition in life is to make a name for myself in music,” and he spent countless hours learning and practicing the songs of other artists while beginning to write and arrange original songs as well.

In 1961, he assembled his first group, The Pendletones, with brothers Carl and Dennis, cousin Mike Love and friend Al Jardine. Wilson and Love first collaborated on the song “Surfin’,” and Murry Wilson became their de facto manager, securing a contract with Candix Records, who insisted on renaming the group The Beach Boys. The song was a regional hit on the West Coast but stalled at #75 on national pop charts, and when Candix went out of business, Murry Wilson persuaded Capitol Records to release demo recordings of two new originals — “Surfin’ Safari” and “409.” The double-sided single reached #14 on US charts in 1962, setting a template for numerous Beach Boys songs about surfing, cars and teenage romance. The group was off and running.

The year 1963 was pivotal for Brian. Not only did he co-write six huge Beach Boys hits with various composing partners (“Surfin’ U.S.A.,” “Surfer Girl,” “Little Deuce Coupe,” “Be True To Your School,” “In My Room” and “Fun, Fun, Fun”), he negotiated with Capitol that he would have complete artistic control as producer on the singles and the albums, spurred on by what he heard on landmark records produced by Spector (especially “Be My Baby” by The Ronettes). Said Wilson years later, “I was unable to really think as a producer up until the time where I really got familiar with Phil Spector’s work. That was when I started to design the experience to be a record rather than just a song.”

Brother Carl concurred: “Record companies were used to having absolute control over their artists. It was especially nervy, because Brian was a 21-year-old kid with just two albums. It was unheard of. But what could they say? Brian made great records.”

Simmering beneath the surface, unfortunately, was a tempestuous relationship between Murry Wilson and the band, especially Brian. The elder Wilson was a controlling, often abusive and violent man, and he took it out on his wife and sons, even as he helped them navigate the music business relationships. As a frustrated singer/songwriter himself, Wilson Sr. demanded to be involved in the music production, with rigid ways of thinking about how things should be done, which annoyed and intimidated the band.

Over the course of Brian’s life, each time his father beat, degraded, or contradicted him, it served as an implicit challenge for Brian to absorb it, maintain stability, and then succeed—all while remaining a dutiful son, subordinate to his father’s authority. As one biographer put it, “Brian had been locked into this existence for most of his life. It wasn’t fair or just, but Brian had handled it so far. He had never broken down, never capitulated, never shown defeat. Neither did he resort to violence or other forms of delinquent behavior, nor did he emulate his father’s narcissism and become an insufferable horse’s ass. All he had done was get better and better at his craft and generate gobs of money.”

Adding to Brian’s anxiety was the arrival of The Beatles in 1964, which had a seismic effect on American teens’ listening habits. I was only nine years old at the time, but I remember thinking the new stuff coming from England was more exciting, more interesting than the sun-and-surf songs of The Beach Boys. Wilson could be fiercely competitive, and was eager to up his game in response. When his father tried to take control of a recording session for “I Get Around,” which would become their first #1 hit, Brian shoved him against a wall and told him to get out. “You’re fired, Dad,” he said, and Murry Wilson was never seen again in their studio, although he kept offering unsolicited advice in conversations with Brian.

Brian Wilson’s perfectionist tendencies and self-imposed pressure to be in charge of their studio output finally got the better of him in late 1964 when he had a panic attack on an airplane and made the fateful decision to quit touring and live performances as a Beach Boy, instead focusing on songwriting and producing. “At that point,” said Wilson in 1990, “I thought I was more of a behind-the-scenes guy than a performer. I still feel that way.”

Songs like “Don’t Worry Baby,” “Help Me, Rhonda” and particularly “California Girls” provided evidence that Wilson was growing more sophisticated and more adept at creating what he called “pop symphonies,” with layered arrangements and the use of novel instruments. This was due in part, many insiders believed, to his first use of psychedelic drugs, which Wilson agreed “made me more introspective, more interested in seeking spiritual, mystical things. It fouled me up for a while, but it also brought on a surge in creativity.”

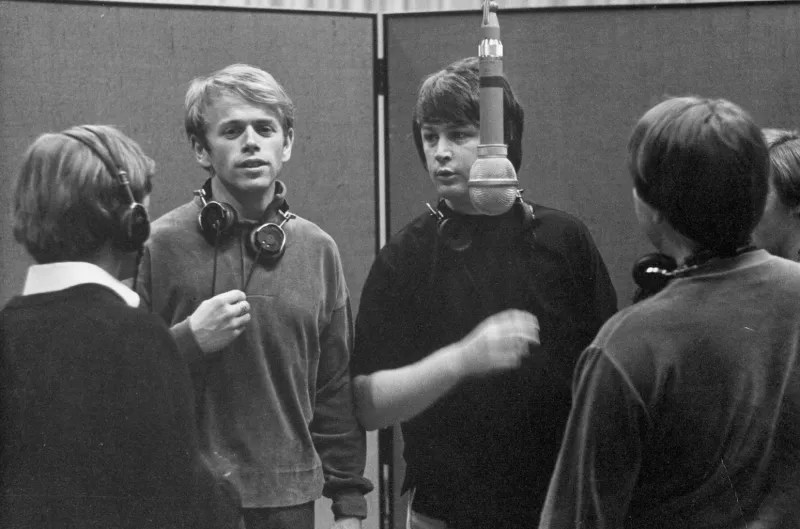

Always striving for perfection in the studio, Wilson insured that his intricate vocal arrangements exercised the group’s calculated blend of intonation, phrasing, attack and expression. Sometimes, he would sing each vocal harmony part alone through multi-track tape. Explained Jardine, “We always sang the same vocal intervals. As soon as we heard the chords on the piano we’d figure it out pretty easily. If there was a vocal move Brian envisioned, he’d show that particular singer that move. We had somewhat photographic memory as far as the vocal parts were concerned, so that was never a problem for us.”

The lyrical approach of Beach Boys songs in 1965-1966 was changing. As writer Nick Kent said, “The subjects of Brian’s songs were suddenly no longer simple happy souls harmonizing their sun-kissed innocence and dying devotion to each other over a honey-coated backdrop of surf and sand. Instead, they’d become highly vulnerable, slightly neurotic and riddled with telling insecurities.”

The release of The Beatles’ superb “Rubber Soul” album in late 1965 was also a big game changer for Wilson. He was immediately enamored with it, declaring, “It had no filler tracks,” a feature mostly unheard of at a time when 45-rpm singles were considered more noteworthy than full-length LPs. “It didn’t make me want to copy them, but to be just as good as they were,” he said. “I didn’t want to do the same kind of music, but on the same level.”

Wilson and his new wife Marilyn moved into a Beverly Hills home, and he began experimenting with the way he composed music, sometimes writing in song fragments which he envisioned as interchangeable modules. He wrote at a furious pace, cranking out some of his most challenging yet satisfying songs to date, and as Jardine explained, “It took us quite a while to adjust to the new material because it wasn’t music you could necessarily dance to. It was more like music you could make love to.”

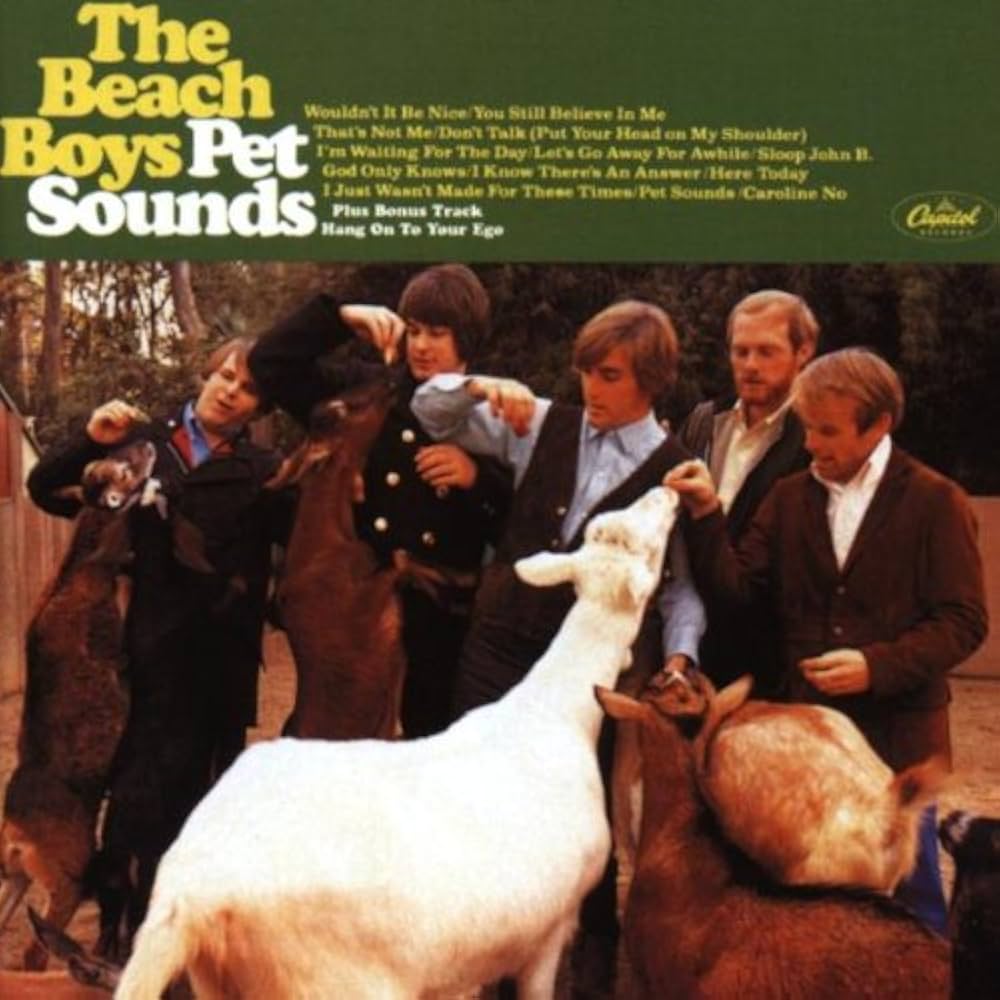

This batch of songs became “Pet Sounds,” the 1966 album widely regarded as Wilson’s (and The Beach Boys’) masterpiece. To capture the sounds he heard and envisioned, Wilson worked in multiple Los Angeles studios, using many outside musicians and limiting the group’s input to vocals only. Introspective love songs and personal reflections (“Caroline, No” and “I Just Wasn’t Made For These Times”) juxtaposed quite effectively next to brilliantly accessible singles like “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” and “Sloop John B.”

The album also featured what is now regarded as perhaps Wilson’s very best composition, “God Only Knows,” which didn’t chart all that well as a single in the US but peaked at #2 in England. Paul McCartney has famously called it “the greatest song ever written.” Brian turned over the lead vocals to his brother Carl, who absolutely nailed the challenging melody line in the official recording. (Forty-odd years later, Brian re-recorded the song handling lead vocals himself, and I’d be hard pressed to choose who does the better job. Both are on my Spotify playlist, so readers can decide for themselves.)

Because the popular response to “Pet Sounds” and “God Only Knows” in the US failed to meet his lofty expectations, Wilson began a long slow descent into self-doubt and paranoia. But before these insecurities took root, he poured all of his efforts into creating “Good Vibrations,” the most ambitious single anyone had ever attempted. Writing, arranging and producing this monumental track took more than six months and cost more in studio time than anyone had spent before. Its unprecedented complexity, episodic structure and use of cellos and Theremins (innovative pre-synthesizers) would’ve been remarkable as an album track, but as a #1 single it was simply extraordinary.

Bassist Carole Kaye, a stalwart member of the group of studio musicians known as The Wrecking Crew, said she was honored to work with Wilson. “By that time, Brian was showing a lot of genius writing. The way he kept changing the music around. He had all the sounds in his head. He knew what he wanted and wrote out the bass parts for me. That wasn’t your normal rock ‘n’ roll. I mean, we were part of a pop symphony.”

Legendary drummer Hal Blaine recalled, “We were laying down instrumental tracks for ‘Good Vibrations’ over seven months. When Brian had a little section of music he wanted to add or change, he’d have us change the trumpet to a sax or the sax to a trumpet, things like that. It was as though he was sculpting the song out of thin air. When I heard ‘Good Vibrations’ in its final form, I was amazed. I had heard only pieces over the seven months we recorded. I happened to speak with The Beatles soon after it came out and they couldn’t believe it.”

Around this time, Wilson was starting to be singled out by industry observers as a genius, significantly more important to the group’s success than the others combined. Mike Love wasn’t so sure about that. “As far as I was concerned,” he said in 1975, “Brian was a genius, deserving of that recognition. But the rest of us were seen as nameless components in Brian’s music machine. It didn’t feel to us as if we were just riding on Brian’s coattails.” Conversely, Dennis Wilson defended Brian’s stature in the band, stating in 1967: “Brian Wilson is the Beach Boys. He is the band. We’re his fucking messengers. He is all of it. Period. We’re nothing. He’s everything.”

In early 1967, Wilson began writing quirkier, more unusual sounds, convinced that the album-in-the-works, entitled “Smile,” would be his finest. But his bandmates and his record label found much of it puzzling, even substandard, which devastated him, and he scrapped the project. “I pulled the plug on it because I felt like I was about ready to die. I was trying so hard. So, all of a sudden, I decided not to try anymore.” One of its tracks, “Heroes and Villains,” was released as a single but it was met with lukewarm response by critics and the public alike, further damaging his morale and bringing on psychological decline.

Beginning with the hastily assembled substitute “Smiley Smile,” The Beach Boys found themselves having to get along without Wilson in his customary leadership role. “My reputation in the industry was a really big thing for me, and I no longer wanted to risk the individual scrutiny,” he said years later. “I let the others take production credit and encouraged them to get more involved in that.”

The next half-dozen albums — “Wild Honey” (1967), “Friends” (1968), “20/20” (1969), “Sunflower” (1970), “Surf’s Up” (1971) and “Holland” (1973) — each had one or two tracks worthy of the group’s catalog, but the general reaction in the US was that time had passed them by. As the group struggled to remain relevant, their finances took a hit and, desperate for cash, they sold their song catalog in 1970 for less than a million dollars, against Wilson’s wishes. He became more and more depressed, reportedly attempted suicide more than once, and became self-destructive, regularly abusing drugs and alcohol.

The depths of his despondence are best illustrated in “‘Til I Die,” a harrowing yet melodic song he wrote for the “Surf’s Up” album. In the lyrics, Wilson describes himself as a small, meaningless object in a grand universe with no control over his trajectory (a cork on the ocean, a rock in a landslide, a leaf on a windy day). “These things I’ll be until I die,” he sings in the chorus, as hopeless as he’s ever sounded. In the 1980s, Wilson called the song “a summation of everything I had to say at the time.”

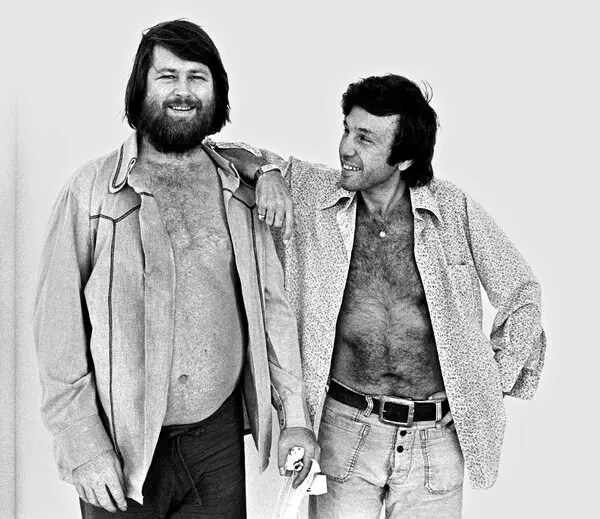

Despite their difficult father-and-son relationship, Murry Wilson’s death in 1973 sent Brian into a deep spiral, isolating himself, overeating, and drinking around the clock. Yet he emerged in 1976 and 1977 to participate significantly in the group’s two comeback LPs, “15 Big Ones” and “The Beach Boys Love You,” which were promoted with a “Brian’s Back!” campaign, and both charted well. That was only a temporary recovery, though; the late 1970s and most of the 1980s saw Wilson on a dark roller coaster of highs and lows, necessitating outside help from therapists, handlers and conservators. He would show improvement, then relapse into even more reckless behavior.

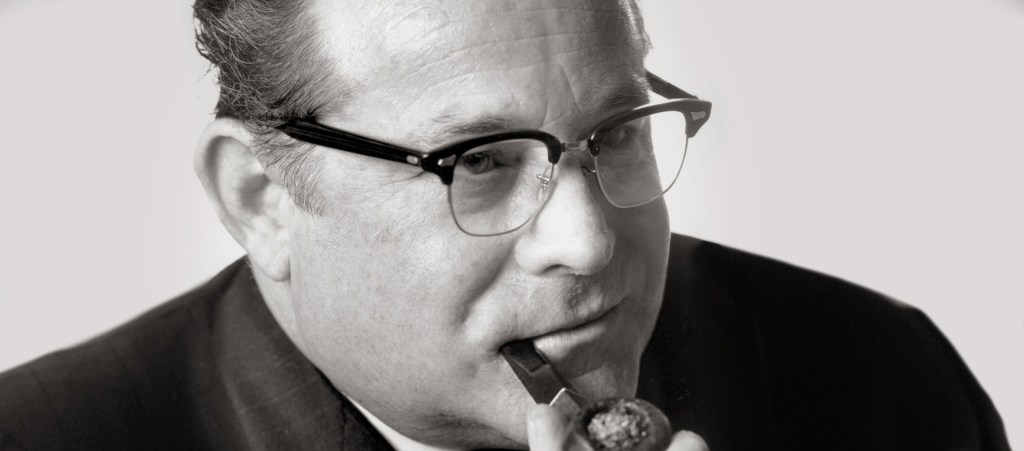

His involvement with psychologist Eugene Landy became all-encompassing, with Landy enforcing an around-the-clock intensive therapy program, eventually controlling Wilson’s finances and becoming his business manager, career advisor and even allegedly his co-songwriter for Wilson’s solo albums in 1988 and 1990. Although Wilson claimed he benefitted from his association with Landy, the state of California eventually charged him with ethics violations and unprofessional conduct, resulting in a restraining order in 1992 from ever contacting Brian again.

I’m not comfortable spending so much space in this piece discussing all of Wilson’s difficulties with mental illness. It’s essentially a very private matter, but sadly, when it happens to a celebrity, and there are public outbursts, it becomes fodder for the tabloids. My suggestion for readers who want to know more is to watch the striking biopic, “Love & Mercy,” a widely praised 2014 deep dive into two distinctly different eras of Wilson’s life story. Actor Paul Dano does a spot-on portrayal of Wilson in his mid-’60s heyday as a studio wizard, and John Cusack handles the more difficult assignment of depicting Wilson during his time under Landy’s care. It’s a remarkable film (Wilson called it “very factual”) that’s well worth your time.

I’m guessing most fans of Wilson and/or The Beach Boys might not be aware that the Canadian band Bare Naked Ladies had a #18 hit in their native country in 1992 with a song called simply “Brian Wilson.” In the lyrics, the narrator describes a life that mirrors Wilson’s during his uneasy time with Landy, mentioning obesity, “Fun, Fun, Fun,” “Smiley Smile” and Landy himself. It’s not a bad tune, but the lyrics cut a little too close to the bone for my tastes. (Nevertheless, I found it interesting enough to include it at the tail end of my Spotify playlist below.)

The last 30-odd years of Wilson’s life continued to have their peaks and valleys. There were joyous reunions and live performances with The Beach Boys, followed by very public spats with Mike Love over royalties and songwriting credits. He also toured on his own with a different band he assembled, and in 2004, he even released “Brian Wilson Presents Smile,” which features all-new recordings of music that he had originally created for the infamous abandoned 1967 Beach Boys project. Love publicly objected, saying it should have been a group release, but Wilson was estranged from the band at the time, and felt victorious about revisiting the material on his own, validated by a #13 charting on US charts.

When asked in 2004 how he managed to stay active as an artist, he simply responded, “By force of will.” A decade later, he expressed pride that he had “proven stronger than many imagined me to be.” It’s a revealing, brave statement from an artist who had spent nearly all his life fighting demons.

In the online music magazine Pitchfork, writer Sam Sodomsky summed it up nicely: “Depending on your age, taste, and life circumstances, you might see Brian Wilson as the sunny figurehead of youthful innocence; the tortured ideal of artistic integrity; the paragon of mastercraftsmanship; or a lovable eccentric who played his grand piano inside a giant sandbox. The common thread through all of these archetypes, of course, is that he endured.”

I was somewhat taken aback that Love, despite his decades-long combativeness toward Wilson, made complimentary remarks about him in the wake of his death. “Today, the world lost a genius,” Love said on June 11th. “I lost a cousin by blood and my partner in music. Brian Wilson wasn’t just the heart of The Beach Boys — he was the soul of our sound.”

Darian Sahanaja, who played in Wilson’s supporting band since 1999, wrote on social media: “I’m now relieved that a man who had suffered nearly every day of his life in a struggle to find some peace and love is suffering no more. I’ve always felt that it was through his struggle, his yearning, his reaching to find a better place that we were given such beautiful music.”

Perhaps Bruce Springsteen put it best when he said, “His level of musicianship—I don’t think anybody’s touched it yet. Brian Wilson was the most musically inventive voice in all of pop, with an otherworldly ear for harmony, and he was the visionary leader of America’s greatest band. Farewell, Maestro.”

*************************

Nearly all of the 55 tracks found on this playlist were written, sung, arranged and/or produced by Wilson during his tenure with The Beach Boys. A few (1988’s “Kokomo,” for instance) had little or no involvement by Wilson, but I included them anyway as part of the broader picture…