I’m gonna tune right in on you

Becoming reacquainted with long lost songs from my youth, or just recently discovering decades-old tunes, are two things that make my day. If you’re a fan of the music of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, then I invite you to join as I feature another dozen “lost classics” from that fruitful era.

I own most of this music on vinyl. Maybe you have it too, or on CD. Or maybe you’re not much of a collector and rely on digital platforms. Regardless, music is meant to be shared, so I’ve assembled a Spotify playlist at the end so you can groove on these tracks as you learn a little bit about them and the artists who recorded them.

Rock on!

***************

“Evil Woman (Don’t Play Your Games With Me),” Crow, 1969

The Minnesota-based band Crow, featuring brothers Larry and Dick Wiegand and singer David Wagner, released three LPs and eight singles between 1969 and 1972, but the only one to make any kind of impact was the solid rocker, “Evil Woman (Don’t Play Your Games With Me),” which reached #19 on US charts in early 1970. It’s interesting to note that Black Sabbath released a cover of the song as their debut single in the UK, but it never saw the light of day in the US until a 2003 compilation CD. Ike & Tina Turner also released a cover of it on their “Come Together” album, changing the gender to “Evil Man” so Tina could sing it.

“Take What You Need,” Steppenwolf, 1968

Gabriel Mekler was a staff producer for ABC Dunhill Records in LA in 1967 when he was assigned to man the boards for a new band known as The Sparrows. Having just read the Herman Hesse novel “Steppenwolf,” he suggested the group adopt that name, then proved instrumental in getting the best sounds out of them for their 1968 debut, especially the landmark single “Born To Be Wild.” Other songs like “The Pusher” and “Sookie Sookie” were written by outside sources (Hoyt Axton and Don Covay respectively), but Mekler co-wrote a couple of songs with lead singer John Kay, including “Take What You Need,” a deep track I’ve always admired.

“Steppin’ Out,” Paul Revere & Raiders, 1965

Guitarist Revere and singer Mark Lindsay headed up this Oregon-based band in the early 1960s, recording mostly covers like “Louie Louie,” “You Can’t Sit Down” and “Do You Love Me,” which earned them a contract with Columbia. They continued recording covers and had their first big hit in 1965 with “Just Like Me,” which led to them becoming the house band on Dick Clark’s afternoon TV show “Where the Action Is.” On their Top Ten album “Just Like Us,” Revere and Lindsay co-wrote a rollicking tune called “Steppin’ Out,” which stalled at #46 on pop charts but still helped pave the way for several more Top Ten hits for the group over the next four years (“Kicks,” “Hungry,” “Good Thing,” “Him or Me, What’s It Gonna Be”).

“Take It Back,” Cream, 1967

Most of Cream’s most memorable recorded moments came when they took established blues songs (“Crossroads,” “Spoonful,” “I’m So Glad”) and turned them into virtuoso live jams. The group also composed their own tunes, with bassist Jack Bruce and his lyricist Pete Brown writing about half the original material found on Cream’s four LPs, including “White Room,” “I Feel Free,” “Politician,” “SWLABR” and “Deserted Cities of the Heart.” Hidden near the end of their popular 1967 LP “Disraeli Gears” is an infectious Bruce/Brown rock track called “Take It Back,” which features great vocals and harmonica by Bruce and uses extraneous voices and noises to convey a party atmosphere in the studio during recording.

“Scarlet Begonias,” Grateful Dead, 1974

As far as radio is concerned, The Dead’s catalog has been largely limited to “Truckin’,” “Casey Jones,” “Sugar Magnolia,” “Friends of the Devil” and “Touch of Grey,” but their repertoire is littered with fun, funky songs just aching to be discovered. I’ve already featured four such Dead tracks in my Lost Classics series (“Eyes of the World,” “China Cat Sunflower,” “Throwing Stones” and “Alabama Getaway”), and now here’s another, this one from their underrated 1974 LP “From the Mars Hotel.” Jerry Garcia and lyricist Robert Hunter wrote it about a mysterious woman they met in London, who wore scarlet begonias in her hair and lured them into a poker game where they lost their shirts.

“Mattie’s Rag,” Gerry Rafferty, 1978

Legal challenges involving his former band Stealers Wheel prevented Rafferty from releasing any new material for four years in the mid-’70s, but once that was settled, he made a big impact with his 1978 LP “City to City,” which reached #1 on US charts on the strength of the hugely popular “Baker Street” single. “Right Down the Line” was a strong follow-up hit at #11, and “Home and Dry” did respectably at #28, but the album offers several more tracks worthy of your attention: the galloping rocker “Waiting For The Day,” the lush ballad “Whatever’s Written in Your Heart” with its stunning harmonies, and “Mattie’s Rag,” a sunny ode to Rafferty’s daughter, telling her how grateful he is to be returning home to her after a long spell away.

“What’s the Matter Here?” 10,000 Maniacs, 1987

This upstate New York band, who got their name from the 1960s low-budget horror flick “Two Thousand Maniacs,” made its first impact on US charts with their “In My Tribe” album in 1987. The LP reached #37, and this single peaked at #9 on the then-new Alternative/Modern Rock chart. Written by singer Natalie Merchant and guitarist Rob Buck, “What’s the Matter Here?” has an upbeat tempo and breezy melody that belies its dark lyrics, which focus on suspected child abuse at the neighbors’ house. One critic said, “The album proves powerful not only for the ideas in the lyrics but also for the graceful execution and pure listenability of the music.” 10,000 Maniacs released several more successful LPs before Merchant left for a solo career in 1993.

“Still Searching,” The Kinks, 1993

While The Kinks had a half-dozen hit singles as a “British Invasion” band in the ’60s, and a #1 with “Lola” in 1970, I always thought radio programmers missed the boat with these guys. Sure, songwriter Ray Davies sometimes went on tangents with eccentric concept albums, but their 25-album catalog is overflowing with catchy pop and straight-ahead rock tunes that should’ve been much bigger on US charts. Their albums in the ’80s sold pretty well here, but only “Come Dancing” made any waves on the Top 40. By 1993, as the band was sputtering to a halt, no one seemed to pay attention to what became their final LP, “Phobia,” which featured the scathing rocker “Hatred” and the charming, melodious “Still Searching.”

“Fig Tree Bay,” Peter Frampton, 1972

Frampton was only 18 when he joined forces with Steve Marriott (ex-Small Faces) to form raucous boogie band Humble Pie in 1969. By 1971, he chose to go solo, writing, producing, singing and playing multiple instruments on his debut LP “Winds of Change,” which had a much greater melodic sensibility than Humble Pie’s oeuvre. Most of the songs featured Frampton on both acoustic and electric guitar, and I recently came across “Fig Tree Bay,” the opening track, and found it engaging. He built a modest following in the US on four solo albums in the mid-’70s before the dam burst open with his double live album “Frampton Comes Alive,” a multiplatinum game-changer that topped the charts for 10 weeks in 1976. I recommend you check out his early studio releases for some truly lost classics.

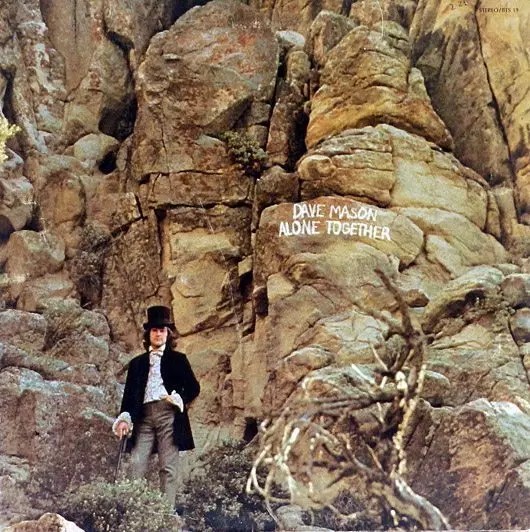

“World in Changes,” Dave Mason, 1970

Much like fellow UK star Frampton, Mason is accomplished as a singer/songwriter as well as both an acoustic and electric guitarist. After two albums as a member of Traffic, Mason found himself at odds with de facto leader Steve Winwood and went the solo route in 1970, finding success right away with the appealing “Alone Together” LP. Aided by the likes of Leon Russell, Delaney & Bonnie and Rita Coolidge, Mason churned out eight memorable tracks, most notably “Only You Know and I Know,” “Sad and Deep as You” and the marvelous “World in Changes.” He toured relentlessly throughout the ’70s and had his biggest hit in 1977 with the 12-string workout, “We Just Disagree.”

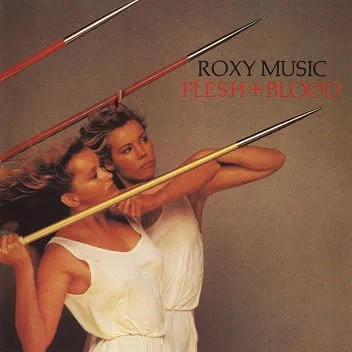

“Oh Yeah!” Roxy Music, 1980

By the time “Flesh + Blood,” Roxy Music’s seventh LP, was released, the band once known for dissonant art rock had evolved its sound into a sleeker, more sophisticated vibe, due in large part to the influence of singer Bryan Ferry. A dreamy, melodic song like “Oh Yeah!” was an early indicator of the kind of music Ferry would write for Roxy’s celebrated swan song, “Avalon,” in 1982, and on his many solo albums over the next 30-plus years. Roxy as a band and Ferry on his own were always a bigger deal in the UK than in the US, but I consider myself among American music lovers who have found Ferry’s later offerings more pleasing to the ear than the early Roxy stuff. “Oh Yeah!” is a classic case in point.

“Hey Papa,” Terence Boylan, 1977

Bet you’ve never heard of this guy, which is a shame. Born and raised in Buffalo, Boylan moved to Greenwich Village in the mid-’60s, and after enrolling at Bard College, he became friends with Walter Becker and Donald Fagen in their pre-Steely Dan years. Boylan wrote and sang his own songs, and his self-titled second album got some airplay and solid critical praise but made no dent in the US charts, even though it contains several great tracks (“Where Are You Hiding,” “Don’t Hang Up Those Dancing Shoes”). One song from the album, “Shake It,” became a minor hit when covered by Ian Matthews in 1978. I’ve always been partial to a pretty piano-based song called “Hey Papa,” about a character who’s a rumrunner in the Florida Keys. Since 1980, he has retired from performing and instead focuses on songwriting and film soundtracks.

**********************