5 o’clock in the morning, I’m already up and gone

In 1882, the first parade that celebrated the contributions of laborers to the country’s development was staged in New York City. Within the decade, more than 30 states were holding their own events honoring workers, and by 1894, Congress passed a bill recognizing the first Monday of September as Labor Day and making it an official federal holiday.

These days, we all enjoy the three-day Labor Day weekend, even though it marks the unofficial end of summer and a return to school. We tend to forget the holiday’s original meaning…but not here at Hack’s Back Pages. For this post, I have collected 20 songs from the classic rock era that celebrate the working men and women that keep our nation humming along. Perhaps you can use the Spotify playlist found at the end of the post as a soundtrack to your weekend activities.

*************************

“Five O’Clock World,” Vogues, 1965

Songwriter Allen Reynolds, who became a successful songwriters’ publisher in Nashville, wrote the workday anthem “Five O’Clock World” in 1965, and it became a Top Five hit for The Vogues, a Pittsburgh-based vocal group that had just scored another Top Five hit with “You’re the One.” Reynolds remembers watching commuters coming and going one weekday morning and thought it would make a great pop song: “Up every morning just to keep a job, I gotta fight my way through the hustling mob, /Sounds of the city poundin’ in my brain while another day goes down the drain…” Artists as varied as country singer Hal Ketchum and synth pop band Ballistic Kisses have covered the song over the years, and The Vogues’ version was used as the theme song for comedian Drew Carey’s workplace sitcom “The Drew Carey Show” in the 1990s.

“Workin’ For a Livin’,” Huey Lewis & The News, 1982

Lewis spent much of the ’70s in San Francisco bars and London pubs as lead singer and harmonica player in various bands. By 1980, he won a record contract as Huey Lewis and The News, and in 1982, the group broke through with “Do You Believe in Love,” a #7 hit on the pop chart. The follow-up single, the energetic “Workin’ For a Livin’,” stalled at #41 but became a fan favorite in concert. Said Lewis, “I wrote it while I was working as a truck driver, and I thought about these other jobs I’d had, like bartender and bus boy.” Lewis re-recorded the song 25 years later in a duet with Garth Brooks, which reached #20 on the country chart: “Hundred dollar car note, two hundred rent, I get a check on Friday, but it’s already spent, /Workin’ for a livin’, livin’ and workin’, I’m taking what they givin’ ’cause I’m working for a livin’…”

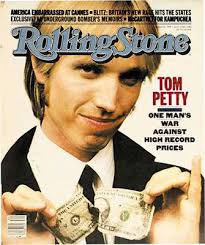

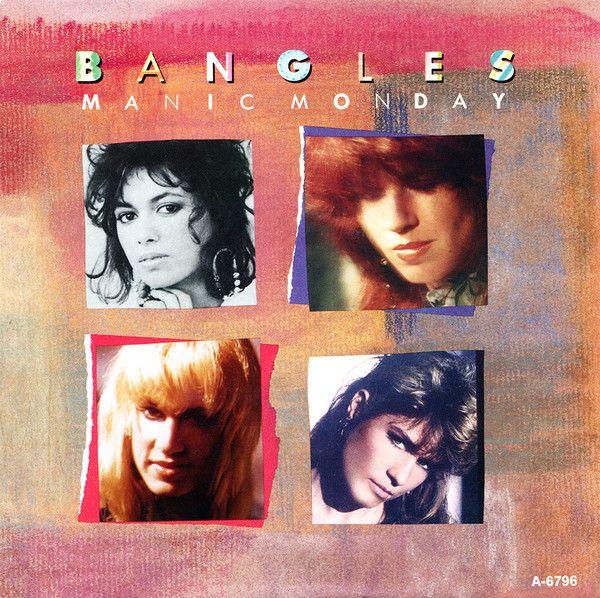

“Manic Monday,” The Bangles, 1986

In the 1960s, The Mamas and The Papas had a #1 hit with their song “Monday, Monday,” the day of the week most people dislike because it signals a return to work after two days off. In 1984, Prince wrote “Manic Monday” about a woman who dreads getting up for work on a Monday morning. He intended to give it to his protégés Apollonia 6, but he didn’t like how it turned out and shelved it. Two years later, he was impressed when he heard The Bangles’ song “Hero Takes a Fall” and decided to offer “Manic Monday” to them. They made it the first of seven hit singles between 1986 and 1989 and, ironically, the record reached #1 the same week Prince’s own single “Kiss” peaked at #2: “It takes me so long just to figure out what I’m gonna wear, /Blame it on the train, but the boss is already there, /It’s just another manic Monday, I wish it was Sunday, /’Cause that’s my fun day, my ‘I don’t have to run’ day…”

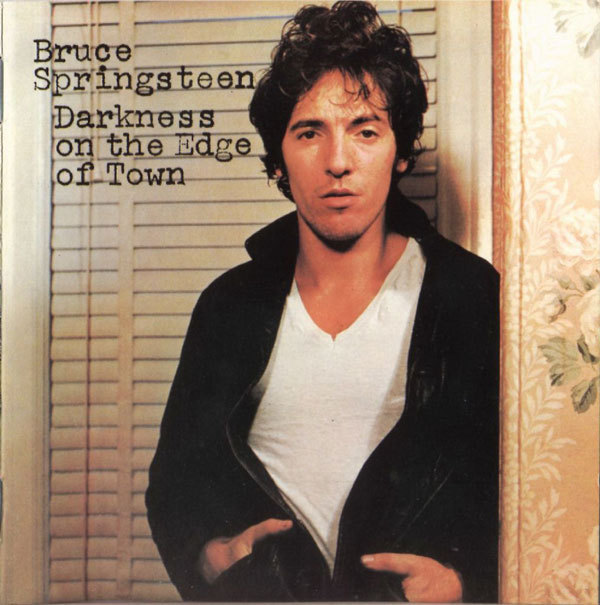

“Factory,” Bruce Springsteen, 1978

Springsteen’s first three albums created characters and settings full of romance and hope, but his fourth LP, “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” is decidedly more downbeat. Critics praised a maturity and evolution in his music and lyrics, noting how punk rock and country music had begun to influence his songs. Boston reviewer Trevor Levin said Springsteen “has perfected a genre of rock meant to embrace working class American life while depicting it as essentially joyless and cursed.” A strong example of this is the deep track “Factory,” a concise study of the dead-end life that awaits factory workers each day: “Early in the morning, factory whistle blows, /Man rises from bed and puts on his clothes, /Man takes his lunch, walks out in the morning light, /It’s the working, the working, just the working life…”

“Blue Collar,” Bachman-Turner Overdrive, 1973

When Randy Bachman left The Guess Who in 1970, he first formed the band Brave Belt and concentrated on country rock material, which never found much of an audience. When C.F. “Fred” Turner joined the lineup on bass and vocals, he also brought a handful of original songs that veered more toward jazz-infused rock. They changed their name to Bachman-Turner Overdrive, signed with a new label and found success with their debut LP in 1973, despite no hit singles. One song, Turner’s delicious “Blue Collar,” stalled at #68 but became a favorite in their concert setlist for years to come as a contrast to the straight-ahead rock of most of their catalog. The song’s narrator sings about the trials and tribulations of working the night shift: “Sleep your sleep, I’m awake and alive, I keep late hours, you’re a nine to five, /So I would like you to know I need the quiet hours to create in this world of mine, /Blue collar…”

“9 to 5,” Dolly Parton, 1980

When Jane Fonda came up with the idea of a film about women office workers, she envisioned it as a drama, “but it was coming across too preachy, too much like lecturing the audience. So we decided to make it a comedy instead.” They hired Director Colin Higgins and said, “What you have to do is write a screenplay which shows you can run an office without a boss, but you can’t run an office without the secretaries.” The resulting film — starring Fonda, Lily Tomlin and breakout star Dolly Parton — was a huge hit, and Parton wrote and sang the infectious theme song, which reached #1 on both the pop and country charts, winning two Grammys. The lyrics paint a bleak picture of how secretaries are treated: “Workin’ 9 to 5, what a way to make a livin’, /Barely gettin’ by, it’s all takin’ and no givin’, /They just use your mind, and you never get the credit, /It’s enough to drive you crazy if you let it…”

“Working Again,” Michael Stanley Band, 1980

Cleveland’s hometown musical hero led one of the best underrated bands in the country during the 1975-1985 period, cranking out dozens of great Midwest rock and roll songs, smartly arranged and produced, but the fame they deserved largely eluded them. MSB, as their fans called them, recorded passionate songs of romance and loss, of dreams and despair, mirroring the lives of the working class kids who made up the bulk of their listening audience. On their 1980 LP, “Heartland,” Stanley wrote “Working Again,” a pounding rock track about the daily grind at work made tolerable by escapist evenings: “I’m gonna make it to the line, and put my time inn, like my old man. before me, died in dreamland with the union by his side, /But not tonight, tonight I’m gonna try a little harder, but come the light, I’m gonna be working, working again…”

“Money For Nothing,” Dire Straits, 1985

Mark Knopfler, the group’s über-talented guitarist/songwriter/vocalist, said he got the idea for this iconic #1 hit while visiting a TV/appliance store. “The lead character in ‘Money for Nothing’ is a guy who works in the hardware department installing all the TVs on the showroom floor. He was watching music videos on the TV screens and commenting disparagingly about the musicians and how ‘That ain’t workin’.’ I borrowed a bit of paper and started to write the song down in the store because I wanted to use a lot of the language that the real guy actually used because it was more real.” One line of the lyric proved controversial: “See the little faggot with the earring and the make-up? /Yeah buddy, that’s his own hair, /That little faggot got his own jet airplane, /That little faggot, he’s a millionaire…” The blue-collar worker showed himself to be jealous of how the rock star earns his money: “You play the guitar on the MTV, /That ain’t working, that’s the way you do it, /Money for nothing, and your chicks for free…”

“Get a Job,” The Silhouettes, 1958

Richard Lewis, Bill Horton, Earl Beal and Raymond Edwards comprised The Silhouettes, one of Philadelphia’s better R&B vocal groups. They scored their biggest hit right out of the gate, “Get a Job,” a doo-wop classic that hit #1 on the pop and R&B charts in 1958 and was covered by many artists and used in such films as “American Graffiti,” “Trading Places” and “Good Morning, Vietnam.” It was Lewis who wrote the lyrics about a man whose wife berates him for his unemployment even though he is desperately struggling to find a job: “Well every morning about this time, (Sha-na-na-na, sha-na-na-na-na), She gets me out of bed, a-crying, ‘get a job!’ (Sha-na-na-na, sha-na-na-na-na), /After breakfast every day, she throws the want ads right my way, and never fails to say, ‘get a job!’…” It turned out to be their only Top 40 chart appearance, and one supposes they all had to get a job at that point.

“Working For the Weekend,” Loverboy, 1981

The Canadian band Loverboy struck big in the US between 1980 and 1985, with four Top 20 albums and nine Top Ten singles on the Mainstream Rock singles charts. One of their biggest was “Working for the Weekend,” which came from guitarist Paul Dean’s experience one weekday afternoon when he was out walking and found the area mostly deserted. “So I’m out on the beach,” he said, “and wondering, ‘Where is everybody? Well, I guess they’re at work. They’re all waiting for the weekend.'” Singer Mike Reno suggested they change the title to “Working for the Weekend.” At the time the song was written, Loverboy was still playing bars and small clubs to little response, but when they played this tune to open one set, “The dance floor was absolutely packed. It pumped them up.” “Everybody’s working for the weekend, /Everybody wants a new romance, /Everybody’s going off the deep end, /Everybody needs a second chance…”

“Work to Do,” Average White Band, 1974

This Scottish R&B band were struggling along in the early ’70s when Eric Clapton’s manager took a shine to their lively neo-soul, flew them to L.A. and put them in the capable hands of producer Arif Mardin. Their self-titled second album vaulted to #1 in the US (#6 in the UK) on the strength of the mostly-instrumental track “Pick Up the Pieces,” which also reached #1. I preferred the B-side of that single, the insistent “Work To Do,” which drove home the idea that, as much as I’d like to spend more time with you, there’s work to be done first: “I’ve been trying to make it, woman, can’t you see? /Takes a lot of money to make it, let’s talk truthfully, /Keep your love light burning, and a little food hot in a plate, /You might as well get used to me coming home a little late, /’Cause I got work to do, I got work, baby…”

“Working Man Blues,” Merle Haggard, 1969

Country music legend Merle Haggard, who helped develop the country sub-genre known as the “Bakersfield Sound,” had a traumatic childhood scarred by his father’s death, a path of petty crime and violence, and multiple incarcerations. By 1960, he straightened himself out, adopting a strong work ethic as he pursued a career in music, writing and recording many dozens of songs and amassing an astounding 38 #1 hits on the country charts between 1965 and 2015. One of his most widely praised tunes is “Working Man Blues” from his 1969 LP “A Portrait of Merle Haggard,” featuring fine guitar work from the wondrous James Burton: “Hey hey, the working man, the working man like me, /I ain’t never been on welfare, that’s one place I won’t be, /’Cause I’ll be working long as my two hands are fit to use, /I drink a little beer in a tavern, sing a little bit of these working man blues…”

“She Works Hard For the Money,” Donna Summer, 1983

After years as a stage performer ion Germany and Austria, Summer returned to the US and became the undisputed “Queen of Disco” with a dozen Top Ten hits, many with longer dance-club versions. In 1983, she was at a private party at a West Hollywood restaurant when she visited the ladies’ room and encountered an attendant who was sound asleep, exhausted from her day-long work shift. “I looked at her,” Summer recalled, “and my heart just filled up with compassion for this lady, and I thought, ‘God, she works hard for the money, cooped up in this stinky little room all night.’ Then a light went off in my head, and I said, ‘She works hard for the money! That’s a song!'” It went to #1: “It’s a sacrifice working day to day for little money, just tips for pay, /But it’s worth it all to hear them say that they care, /She works hard for the money, so you better treat her right…”

“Bus Rider,” The Guess Who, 1970

Following the release of their big #1 hit “American Woman,” The Guess Who parted ways with founding member Randy Bachman, leaving keyboardist-vocalist Burton Cummings in charge. His first move was to hire two guitarists, Kurt Winter and Greg Liskiw, who took turns beefing up the arrangements with sizzling solos and fills. Cummings continued writing irresistibly catchy tunes that became great radio fare (“Share the Land,” “Albert Flasher,” “Rain Dance”), but Winter also had a knack for songwriting, as evidenced by the hit “Hand Me Down World” and its B-side, “Bus Rider,” an ode to the working stiff. With Cummings on piano and vocals, “Bus Rider” became one of my favorite Guess Who tunes: “Leave the house at six o’clock to be on time, /Leave the wife and kids at home to make a dime, /Grab your lunch pail, check for mail in your slot, /You won’t get your check if you don’t punch the clock, /Bus rider…”

“I’ve Been Working,” Van Morrison, 1970

The free, relaxed sound that Morrison conjured for his iconic “Moondance” LP in 1970 was markedly different from the quieter, more vulnerable vibe of his “Astral Weeks” album before it. Morrison originally intended that the next project be recorded a cappella with a small chorus, but he ended up using the same backing musicians from the “Moondance” album and tour, and additional voices, and the record company saw fit to call the album “His Band and The Street Choir.” One track, “I’ve Been Working,” had been tried twice before in earlier album sessions, and the third time captured a wonderfully hypnotic groove based around the opening lyric “I’ve been working so hard” and “I’ve been grinding so long,” devolving into “woman, woman, woman, woman” and “all right, all right, all right, all right.”

“Out of Work,” Gary U.S. Bonds, 1983

Gary Anderson, who later adopted the stage name Gary U.S. Bonds, scored four Top Ten hits in the early ’60s, most notably the rave-up “Quarter to Three,” a feisty little blues rocker that topped the charts in 1961. Bonds proved to be an early influence on Bruce Springsteen, who was happy to use his clout to help revive Bonds’ career in the early 1980s, writing ten songs that appeared on two Bonds LPs in 1982 and 1983. Most notable were the hit singles “This Little Girl” and “Out of Work,” both of which benefitted from the participation of The E Street Band in the studio. In “Out of Work” (basically a rewrite of Springsteen’s “Heavy Heart”), Bonds sings lyrics that struck home with many during the Reagan recession: “8 A.M., I’m up and my feet beating on the sidewalk, /Down at the unemployment agency, all I get’s talk, /I check the want ads but there just ain’t nobody hiring, /What’s a man supposed to do when he’s down and out of work, I need a job, I’m out of work…”

“The Working Man,” Creedence Clearwater Revival, 1968

John Fogerty was still honing his songwriting chops when his band Creedence Clearwater Revival recorded their debut LP in 1968. While he went on to write a dozen Top Ten hits over the next four years, at that point, the group’s best efforts came on the Dale Hawkins classic “Susie-Q” and the Screamin’ Jay Hawkins slow blues, “I Put a Spell on You.” Wedged between those two tracks was a Fogerty original called “The Working Man,” which served as a prototype for later Creedence songs like “Penthouse Pauper” and “Tombstone Shadow.” The song’s lyrics laid out Fogerty’s no-nonsense work ethic: “Well, I was born on a Sunday, on Thursday, I had me a job, /I was born on a Sunday, by Thursday, I was workin’ out on the job, I ain’t never had no day off since I learned right from wrong…”

“I’ve Been Working Too Hard,” Southside Johnny and The Asbury Jukes, 1991

One of the great unheralded bands from the ’70s/’80s was this group of R&B devotees from the Jersey shore fronted by singer John Lyons. Their first three LPs in 1976-1978 received immeasurable support from Lyons’ longtime pal Steve Van Zandt, who wrote and/or produced most of the best songs in the Asbury Jukes catalog. So it was only natural that, after suffering a rough patch in the late ’80s, Lyons called upon Van Zandt to fuel his comeback LP, “Better Days.” One of the highlights from that disc is “I’ve Been Working Too Hard,” a glorious, horns-driven rocker: “Now, money and me don’t talk too much, we never got along too well, /But when I got some in my pocket, I seem to have a lot more friends, /I pay the landlord and the taxman, and it’s time to go to work again, /Can I get a witness? /Let me hear you say, I’ve been workin’ too hard…”

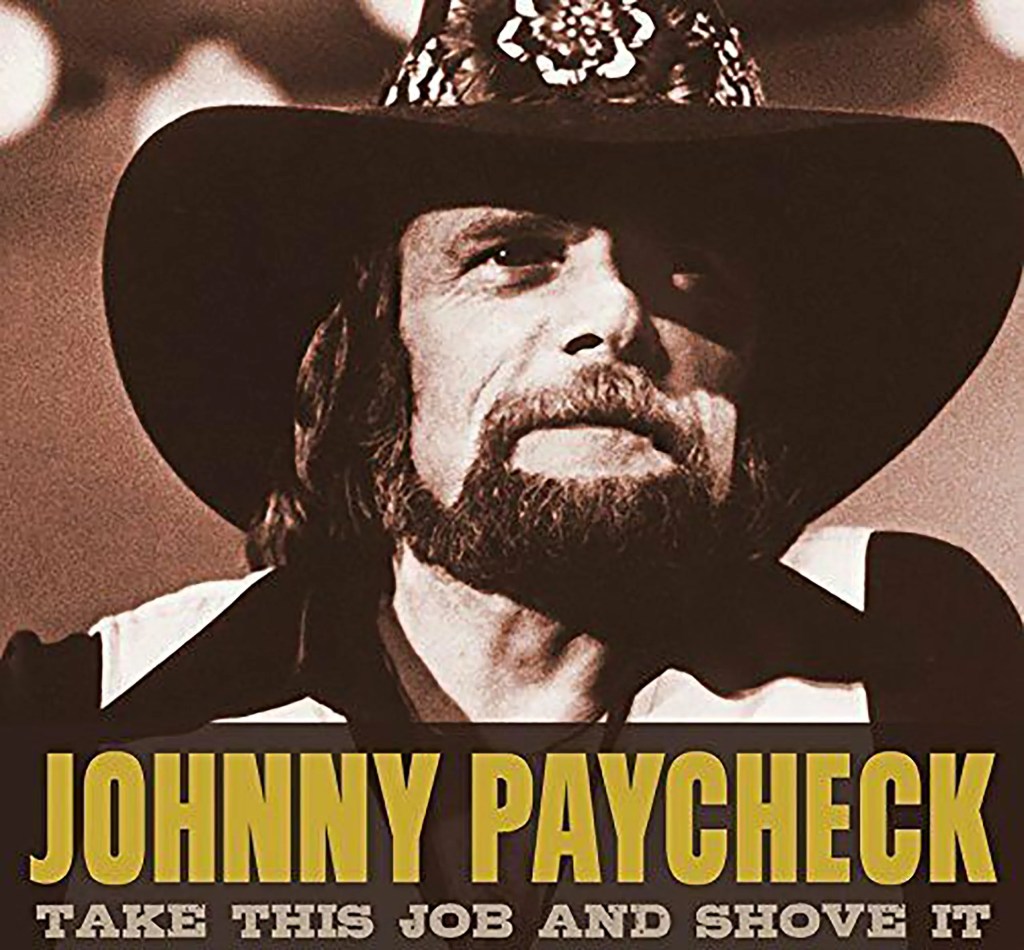

“Take this Job and Shove It,” Johnny Paycheck, 1982

Donald Lytle was a harmony singer for country music legends like Ray Price and George Jones before he changed his name to Johnny Paycheck (contrary to popular myth, it was not meant as a parody of Johnny Cash). In the late ’70s, Paycheck became part of the outlaw country scene alongside Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Hank Williams Jr., and enjoyed his own #1 song on the country charts, the iconic “Take This Job and Shove It.” Written by fellow outlaw David Allan Coe, the song’s title became a ubiquitous phrase in popular culture, not only among unhappy employees but among those who could no longer tolerate their car, their spouse, their whatever: “One of these days I’m gonna blow my top, and that sucker, he’s gonna pay, /Lord, I can’t wait to see their faces when I get the nerve to say, /Take this job and shove it, I ain’t working here no more…”

“Takin’ Care of Business,” Bachman-Turner Overdrive, 1973

In addition to the previously mentioned “Blue Collar,” BTO also recorded what may be the quintessential song about the working life. While still in The Guess Who, Randy Bachman had written a tune he called “White Collar Worker,” but when he found himself at odds with the rest of the band, he departed, forming another group called Brave Belt, which morphed into Bachman-Turner Overdrive by 1973. He revived “White Collar Worker” for their setlist, but one day, he heard a Vancouver radio deejay say, “We’re takin’ care of business here at CFUN Radio,” and decided to insert the phrase in the chorus where “white collar worker” had been. The crowd ate it up, stomping and shouting along to what became the song’s new title when they recorded it weeks later. It’s one of BTO’s signature songs, and an anthem of the working world: “You get up every morning from your ‘larm clock’s warning, take the 8:15 into the city, /There’s a whistle up above, and people pushin’, people shovin’, and the girls who try to look pretty, /And if your train’s on time, you can get to work by nine, and start your slaving job to get your pay…”

****************************

Honorable mention:

“Welcome to the Working Week,” Elvis Costello, 1977; “Working Girl,” Cher, 1987; “Working in the Coal Mine,” Lee Dorsey 1966; “Morning Train (Nine to Five),” Sheena Easton, 1980; “Bang the Drum All Day,” Todd Rundgren, 1982; “Working John, Working Joe,” Jethro Tull, 1980; “Working Man,” Rush, 1974; “Chain Gang,” Sam Cooke, 1960.

****************************