Shapes of things before my eyes

Periodically, I have used this space to pay homage to artists I believe are worthy of focused attention — artists with an extraordinary body of work and/or a compelling story to tell. In this essay, first published here in 2016, I pay homage to a band from the 1960s whose ranks have included some of rock music’s biggest talents: The Yardbirds.

********************

When we talk about influential rock bands of the ’60s, we usually hear the same well-known names: The Beatles. The Beach Boys. The Rolling Stones. The Who. The Byrds. The Grateful Dead. All worthy candidates.

But there’s another band that arguably tops them all: The Yardbirds.

Casual rock music listeners will say, “Huh?” They might remember the 1965 pop hit, “For Your Love,” and some may recall the 1966 harder-edged singles “Shapes of Things” and “Heart Full of Soul.” But that’s about it.

Some rock historians maintain that, when it comes to making a seismic impact on many dozens of artists and bands that followed in their wake, you can make a strong case that The Yardbirds win the contest hands down.

For the uninitiated, here’s the deal: The Yardbirds were born in 1963 as a blues-focused band out of London. Their first guitarist didn’t last and was soon replaced by 18-year-old Eric Clapton as the lead guitarist. By 1965, Clapton had moved on, and in his place, the group was steered by the great guitar pioneer Jeff Beck. In 1966, Beck overlapped briefly with his eventual successor, veteran studio guitarist Jimmy Page.

That’s right: The three recognized kings of electric guitar and British rock/blues, who all ranked in the Top Five on Rolling Stone‘s Top 50 Guitarists of All Time, were all graduates of “Yardbirds University.”

The History

England in the late ’50s and early ’60s was still recovering from the shell shock of World War II, and as far as popular music was concerned, the teenagers growing up in that era didn’t know much more than what the staid BBC was willing to feed them — dance hall music, classical, show tunes and the like. But the new music of America filtered in from the seamen who returned from the US with the latest 45s of bold new genres known as Jazz, and The Blues.

Young Britishers like Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies were entranced. They learned the riffs, the grooves, the feel for it all, and even opened a club called “London Blues and Barrelhouse Club,” which featured American blues artists like Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim. Young Brits starved for something more than the usual BBC fare frequented the place, and Korner and Davies formed a band called Blues Incorporated, which became a breeding ground for young British musicians similarly mesmerized by this compelling new music.

Four of these guys, all fanatical about blues music, were Keith Relf (singer and harmonica player), Paul Samwell-Smith (bass), Jim McCarty (drums) and Chris Dreja (rhythm guitar), who were eager to start their own band. With “Top” Topham on lead guitar, they formed the Blue-Sounds, and were thrilled to support Davies on several gigs in early 1963.

They soon renamed themselves The Yardbirds, named after the nickname of wanderers who hung out in railyard stations, and for the great jazz saxophonist Charlie “Yardbird” Parker.

They drew considerable attention around London playing the Chicago blues tunes of Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, Bo Diddley, Howlin’ Wolf and Elmore James, future classics like “Smokestack Lightning,” “Boom Boom” and “I’m a Man.”

The Clapton Era

In October 1963, Topham grew bored and left, and in walked Eric Clapton, a remarkably accomplished guitarist despite being only 18. He’d cut his teeth in a couple bands (The Roosters, Casey Jones & The Engineers) and was a disciple of Delta bluesman Robert Johnson, and idolized American blues guitarists like B.B. King, Buddy Guy and Freddie King. Bringing Clapton into The Yardbirds helped them secure a gig as the new house band at the famed Crawdaddy Club in suburban Richmond, succeeding The Rolling Stones there. That, in turn, helped them land a recording contract with EMI’s Columbia label in 1964.

Clapton steered The Yardbirds deeper into blues material, as evidenced by their first two singles, “I Wish You Would” and “Good Morning, Little School Girl.” Manager/producer Georgio Gomelsky was the man behind the band’s first LP, “Five Live Yardbirds,” recorded in concert at the legendary Marquee Club in London. Despite favorable reviews in R&B circles, it failed to make the charts in the UK and was never released in the US.

Eager to follow the path of other British blues bands like The Animals, who had a huge international hit with “House of the Rising Sun,” the Yardbirds agreed to record “For Your Love,” a decidedly commercial pop song by Graham Gouldman, who also wrote songs for The Hollies and Herman’s Hermits. Sure enough, “For Your Love” quickly climbed the charts in early 1965, reaching #3 in England and #6 in the US.

But Clapton, a diehard blues purist, was not happy. He heatedly objected to the commercial pop direction the band was taking, and even as “For Your Love” was establishing The Yardbirds as a success, he abruptly left. “I am, and always will be, a blues guitarist,” he said years later. “It was a very powerful drug to be introduced to me, and I absorbed it totally. I didn’t care for pop music at that time. Blues was it for me.”

Clapton soon hooked up with another blues purist, John Mayall, and became one of his Bluesbreakers for a spell, which included the indispensable LP “Bluesbreakers With Eric Clapton” (1966). He reached worldwide fame as part of the improvisational power trio Cream (1966-1968), the short-lived supergroup Blind Faith (1969), the drug-plagued Derek and the Dominos (1970-1971) and, eventually, a long solo career that has spanned six decades. He has won multiple Grammys and been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame three times (for Yardbirds, Cream and as a solo artist). He is often regarded as the finest rock/blues guitarist of all time.

The Beck Era

Before departing The Yardbirds, Clapton suggested the band hire veteran studio guitarist Jimmy Page to replace him. But Page turned them down, preferring the lucrative work he’d been getting in regular studio sessions. He, in turn, suggested Jeff Beck, who eagerly joined the lineup in April 1965.

Beck had most recently been in The Tridents, another London blues group, where he was known for innovations with guitar fuzz tone, sustain, feedback and distortion. He brought all that and more to The Yardbirds, first heard on their next hit single, “Heart Full of Soul,” which peaked at #2 in the UK and #9 in the US in the summer of ’65. Beck’s brief but meaty solos in tracks like “Shapes of Things” and “Over Under Sideways Down” were mini-masterpieces of early heavy metal techniques. Dozens of guitarists who followed — Ritchie Blackmore (Deep Purple, Rainbow), Kirk Hammett (Metallica), Tony Iommi (Black Sabbath) — often name Beck as a key influence in their own musical paths.

The Yardbirds gave Beck ample room to try new things, which suited him fine. “I don’t understand why some people will only accept a guitar if it has an instantly recognizable guitar sound,” he said in 1975. “Finding ways to use the same guitar that people have been playing for years to make sounds no one has heard before — that’s truly what gets me off.”

With Beck, the band released the seminal album “Roger the Engineer,” seen now as the peak of their recorded work. But Beck was developing a rebellious nature, and combined with a perfectionist attitude and an unpredictable temper, he often alienated the rest of the group, especially bassist Samwell-Smith, who chose to leave in mid-1966 to become a respected producer.

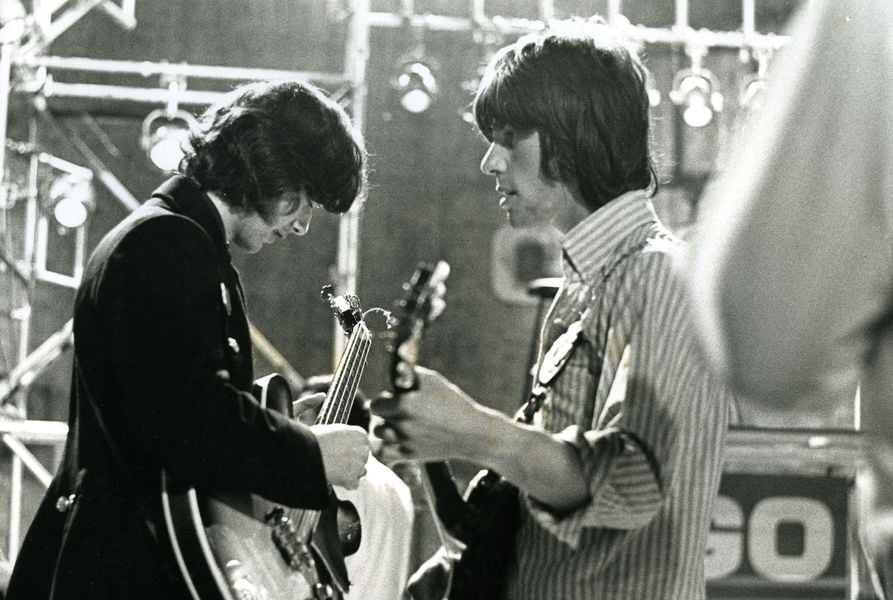

Once again, The Yardbirds approached Page, this time asking if he would join as their bass player. He agreed, but Relf soon assumed the role of bassist, and Page became their second lead guitarist. Page and Beck shared lead guitar duties in concert, which sounds like a dream come true, but sadly, there are very few recordings of the two of them together. (Indeed, ’70s guitar great Ronnie Montrose recalls, “Seeing the original Yardbirds with Beck and Page together at the old Fillmore was a pretty powerful influence on me.”)

That arrangement lasted only three months. Beck’s habit of not showing up for concert dates became a dealbreaker for the other Yardbirds, and in November 1966, during a US tour, Beck was unceremoniously fired. “I probably deserved it,” he said years later. “I was a bit of a prick.”

Bruised but not beaten, Beck went on to a colorful solo career, starting with the phenomenal “Truth” LP in 1968, featuring a young Rod Stewart on vocals, Ronnie Wood on guitar and bass and Nicky Hopkins on piano. He has played with many other musicians from different genres, including Tim Bogert and Carmine Appice from Vanilla Fudge, keyboard legend Max Middleton, and jazz keyboardist Jan Hammer, most notably on “Blow By Blow” (1975) and “Wired” (1976), his best-charting albums in the US (#4 and #16 respectively). His recorded output has been sporadic, but his occasional jaw-dropping appearances at major rock events in recent years has cemented his status as a “guitarist’s guitarist.” He has twice been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, as a Yardbird in 1992 and as a solo artist in 2009. He passed away in 2023 at age 78.

The Page Era

Before joining The Yardbirds, Page had already established a formidable reputation as a skillful studio guitarist, playing on recording sessions for dozens of British acts like The Kinks, Donovan, Joe Cocker, Petula Clark and Marianne Faithful. “It was lucrative and exciting for a while,” Page said, “but then it turned dull and uninspiring when they had me doing incidental film soundtracks and Muzak.” So when the Yardbirds came calling, this time he said yes.

Following the aforementioned stints on bass and then sharing guitar duties with Beck until his departure, the band carried on as a four-piece (McCarty on drums, Dreja on rhythm guitar, Relf on bass and vocals, and Page on lead guitar). Psychedelic rock was becoming the rage as Jimi Hendrix, Cream, The Grateful Dead and others led the way. Page was intrigued by the possibilities and steered the band in that direction. The album they came up with, “Little Games,” was all over the map, thanks in large part to the record company (Epic) insisting on pop producer Mickie Most’s involvement. The album stalled at #80 in the US, and the single “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago” managed only #30 here. The commercial singles Most produced for them fared even worse, many not even charting in the US nor the UK.

In concert, The Yardbirds were almost like a different band. Page took them through the paces: long jams on old standards like “Smokestack Lightning,” covers of Velvet Underground songs, Eastern-flavored tour-de-forces like “White Summer,” and an electrified folk ballad by American Jake Holmes called “Dazed and Confused,” on which Page used a cello bow to coax bold new sounds from his Les Paul guitar (a clear sign of things to come).

By mid-1968, the band was fracturing. Relf and McCarty wanted the group to pursue elements of folk and classical music in their repertoire; Page was firmly headed toward the heavier blues rock idiom; Dreja, meanwhile, had developed an interest in rock photography. Clearly, it was time to call it quits. Relf and McCarty left, and made good on their dream by forming the classical rock group Renaissance.

Page, meanwhile, started looking around for other musicians to form a new Yardbirds lineup, in part because he needed to honor a set of Scandinavian concert dates in late 1968. But more pointedly, he had slowly been building “a textbook of ideas” during his tenure in the band, and was already envisioning his own group. He contacted accomplished keyboard/bass wizard John Paul Jones, another veteran of numerous ’60s studio sessions. Page also approached promising singer Terry Reid to join, but he had just signed a solo recording deal, so he declined. But he sent Page to check out a then-unknown vocalist named Robert Plant, who was turning heads in Band of Joy up in Birmingham. Page was blown away by what he heard and invited him to join his “New Yardbirds,” along with Band of Joy’s explosive drummer, John Bonham.

This new foursome rehearsed intensely for two weeks and then played the shows in Scandinavia, where the crowds were bowled over by the group’s power and intensity. In order to make a clean slate, Page dropped the New Yardbirds name and substituted a phrase that drummer Keith Moon of The Who had once used to describe a band that would fail badly: “Lead Zeppelin.” Manager Peter Grant suggested changing “lead” to “led” so people wouldn’t mispronounce it, and voila! The greatest rock band of the 1970s, Led Zeppelin, was born.

The Aftermath

Many dozens of Yardbirds compilations, live recordings (official and bootleg), stray singles and B-sides emerged in the ’70s and ’80s and beyond, as a new generation of rock fans were curious to hear Clapton, Beck and Page in their formative years. Sometimes it’s difficult to tell whose guitar licks you’re hearing, particularly on tracks from the period Beck and Page overlapped. But there are some real jewels in there for those willing to dig through the mixed bag of 1964-1968 recordings.

And what of the other alumni? Sadly, Relf met his untimely end when he was electrocuted in his home recording studio in 1976. Dreja and McCarty attempted a reunion in the early ’80s, and assembled a new lineup as recently as 2003 when they released “Birdland,” with re-recordings of eight classic Yardbirds tracks along with seven new ones. It didn’t sell or chart, but I found it entertaining. You can check out some of it on the Spotify playlist below.

**************************