I never weep at night, I call your name

I remember when I was young thinking how cool it would be to have a song named after you. Well, not me personally, but a song that was entitled “Bruce.” I soon learned, however, that while there are many dozens, even hundreds, of songs named after women, there are only a handful featuring men’s names. Elton John’s “Daniel” comes immediately to mind, or that macabre tune from 1971 which features two boys who apparently ate their friend in order to survive being trapped in a mine (“Timothy, Timothy, where on earth did you go?”).

Men (and a few women) have been writing songs about the women in their lives for at least a century or two. These tunes have come in the form of romantic ballads, bitter break-up songs, heartfelt tributes and bittersweet odes.

More often than not, songwriters don’t mention these women by name, perhaps to preserve anonymity, or because their manager urged them to keep it more generic so the song might have more universal appeal. But sometimes a writer insisted on keeping it specific to pay homage, or to hold in contempt, or simply because the sound of the name fit nicely in the song’s meter.

There are several dozen pretty great examples of classic rock songs with women’s names as the title. No modifiers, no extra words. Just the name.

In searching for these titles, I came across many others that use women’s names with descriptors (“Judy in Disguise,” “Long Tall Sally”), verbs (“Come on Eileen,” “The Wind Cries Mary”) and other qualifiers (“Mary Jane Can’t Dance,” “Caroline No”). All perfectly good songs, but I limited my list to one-word titles.

Here are 20 for your consideration, with another baker’s dozen “honorable mentions.” There’s my usual Spotify playlist at the end. Enjoy!

**************************

“Sara,” Fleetwood Mac, 1979

It took a while, but in 2014, Stevie Nicks finally confirmed what had been rumored for quite some time — that this 1979 song from Fleetwood Mac’s “Tusk” LP is about an aborted child she and lover Don Henley chose not to have. “Had we gotten married and had that baby, and if it had been a girl, her name would have been Sara,” Nicks said. “It’s a special name to me. One of my very best lifelong friends is named Sara.” The recording reached #7 as a single in early 1980, and Nicks still performs the song, both with the band and as a solo act.

“Roxanne,” The Police, 1978

In 1977, when The Police were performing in dive clubs around Europe, Sting was inspired by the prostitutes who worked outside the seedy hotel in Paris where the band was staying. He wrote this sympathetic tune, urging the woman to give up the hard life she had chosen. He decided to call her Roxanne after seeing a movie poster in the hotel lobby featuring the old film “Cyrano de Bergerac,” whose female lead is named Roxanne. The song peaked at only #32 in the US in 1978, but it remains one of The Police’s signature songs.

“Gloria,” Them, 1964

Van Morrison said he wrote “Gloria” in the summer of 1963 as he was turning 18. The song is as simple as it gets, only three chords, and he often ad-libbed lyrics as he performed it, sometimes stretching the song to 15 or 20 minutes. Gloria was a real person, a girl he was infatuated with, and his desire to seduce her made it more challenging for some ’60s radio programmers to include the song in Top 40 formats. Indeed, when an obscure group called The Shadows of Knight had a Top 10 hit with their cover of “Gloria” in 1966, it eliminated the reference to “coming up to my room.”

“Victoria,” The Kinks, 1969

In the leadoff song on The Kinks’ criminally underrated 1969 LP “Arthur,” Ray Davies’ satirical lyrics juxtapose the grim realities of life in Britain during the 19th century (“Sex was bad and obscene, and the rich were so mean”) with the empathetic hopes of the British Empire in the Victorian age (“From the West to the East, from the rich to the poor, Victoria loved them all”). Throughout her reign, Queen Victoria was beloved even by the downtrodden working class (“Though I am poor, I am free, when I grow, I shall fight, for this land I shall die”). The song? Not so much — it managed only #33 in the UK and stalled at #62 in the US, despite its catchy melody.

“Jolene,” Dolly Parton, 1973

Parton’s solo career was just gathering momentum when she penned this evocative song about a simple gal who pleads with a stunningly beautiful woman named Jolene to leave her man alone: “Pretty girl, please don’t take my man just because you can.” So many country music fans could relate to that woman’s desperate feeling that the song soared to #1 on the country charts (although only #60 on the pop charts). It became one of Parton’s most loved tunes, and many cover versions have been recorded since. There was even a song called “Diane” by country singer Cam in 2017 that serves as a sequel to “Jolene” in which the pretty woman apologizes, saying she was duped by the cheating man.

“Amie,” Pure Prairie League, 1972

Craig Fuller was the chief singer-songwriter in the original lineup of the country rock group Pure Prairie League, and he wrote great down-home songs on those classic but largely overlooked first two albums in 1971 and 1972. One song, “Amie,” didn’t do much at first but eventually earned listeners through FM and college radio stations, and by 1975, it was a #27 hit nationwide. The narrator and Amie have one of those on-again, off-again relationships, and it’s never clear whether they end up together. As Fuller said later, “The protagonist of the song is just laying it out there, and the rest is up to her.”

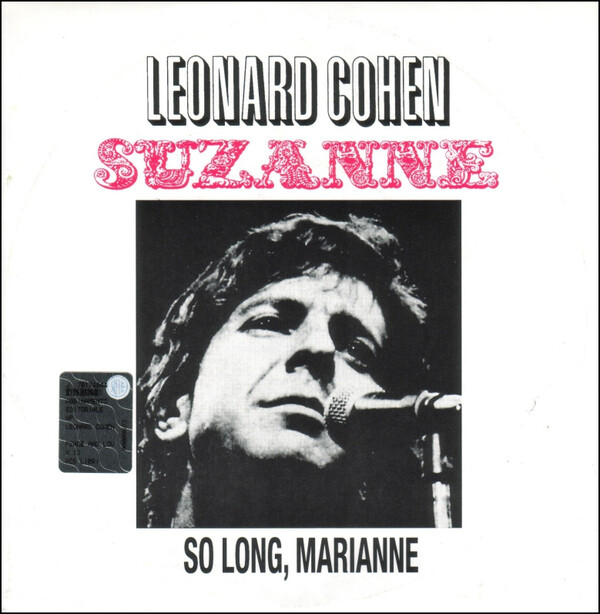

“Suzanne,” Leonard Cohen, 1967

Cohen said “Suzanne” was inspired by his platonic relationship with a woman named Suzanne Verdal, who had been the girlfriend of one of his contemporaries, the famed sculptor Armand Vaillancourt. The lyrics deftly describe the rituals they enjoyed in Montreal, where they lived near each other. Contrary to some interpretations, Cohen insisted he and Suzanne were only friends, not lovers. “I admit I imagined having sex with her, but there was neither the opportunity nor the inclination to actually go through with it,” he admitted. It never charted in the US, but it was one of his signature tunes, and after Cohen’s death in 2016, “Suzanne” reached the Top Ten in France and Spain.

“Martha,” Tom Waits, 1973

From the 1970s to the current day, Waits has been known for his distinctive deep, gravelly singing voice and song lyrics that focus on the underside of U.S. society. Many of the characters who populate his music are unpleasant ne’er-do-wells and unsympathetic outliers, but a few reek of pathos, such as Tom Frost, the elderly guy who places a phone call to “Martha,” an old flame with whom he is meekly hoping to rekindle something. It becomes clear that that’s not going to happen, but we listeners feel supportive of Tom’s wistful trip down memory lane to speak with her once again.

“Maybellene,” Chuck Berry, 1955

Berry wrote and recorded this prototype rock and roll song as an adaptation of the Western swing fiddle tune “Ida Red,” recorded in 1938 by Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. Leonard Chess, owner of the legendary Chess Records label, loved Berry’s sprightly lyrics about a hot rod race and a broken romance, but told him he felt the woman’s name needed to be something less rural than Ida Red. He spied a bottle of Maybelline mascara in the studio and said, “Well, hell, let’s name her Maybellene,” altering the spelling to avoid a potential suit by the cosmetic company. It reached #5 on US pop charts in 1955 as one of the first-ever rock ‘n’ roll songs.

“Cecilia,” Simon and Garfunkel, 1970

This #4 hit, among Simon and Garfunkel’s final chart singles, began life as a cacophony of rhythms pounded out on coffee tables and kitchen counters in Simon’s apartment. He later wrote the lyrics as a reflection about anguish and jubilation regarding an untrustworthy lover. “Cecilia,” Simon has noted, refers to St. Cecilia, patron saint of music in the Catholic tradition, and he conceded that the song also refers to the frustrations and joy he has experienced in the songwriting process, as musical inspiration often arrived and departed quickly for him.

“Melissa,” The Allman Brothers Band, 1972

Gregg Allman wrote the acoustic tune “Melissa” back in 1967 when he and his brother were recording and performing as The Allman Joys. “Duane adored that song,” Gregg said, “which was one of the first decent tunes I wrote after many failed attempts. I always thought it was too mellow for The Allman Brothers Band, and I was saving it for a solo album I figured I’d put out eventually.” When Duane died at only 24 in 1971, Gregg was persuaded to record it with the band as a tribute to his brother for their “Eat a Peach” album in 1972, and it became a regular part of the band’s set list over the years since.

“Rachel,” Emily Hackett, 2020

My daughter Emily has been writing, recording and performing music since her high school days, and her sister Rachel has always been her biggest fan. In 2020 during the pandemic, “She had just given me an epic present for my 30th birthday,” Emily recalled. “I decided it was high time I wrote a song for her, so I sat on my front porch and wrote ‘Rachel’ as if I was writing a letter. It came fast. I think the lyrics really nail who she is. ‘A golden ray of sunshine.’ ‘Her eyes are so blue, it’s painful.'” She produced it herself in time for Rachel’s 27th birthday and released it three weeks later. I cherish this song.

“Julia,” The Beatles, 1968

During the sessions for The Beatles’ “White Album,” John Lennon was burning with a desire to write a song about his mother, Julia Baird. “I lost her twice,” he said, “once as a five-year-old when I was moved in with my auntie, and then again when she physically died when I was 17.” He borrowed phrasings from Kahlil Gibran’s “Sand and Foam” in which the original verse reads, “Half of what I say is meaningless, but I say it so the other half may reach you.” Although it’s a Beatles track, no one but the composer was present for the recording, which featured Lennon alone on acoustic guitar and vocal.

“Angie,” The Rolling Stones, 1973

When the Stones reached #1 on the charts with the ballad “Angie” in the fall of 1973, speculation was rampant about the identity of the woman in question. Some said Jagger and Richards were writing about David Bowie’s first wife Angela, with whom they had been spending time during that period. Others assumed it was a tribute to Richards’ newborn daughter, Dandelion Angela. In his 2010 autobiography “Life,” Richards said that he had chosen the name at random when writing the song, before he knew that his daughter would be named Angela or even knew that the baby would be a girl.

“Rosanna,” Toto, 1982

This Song of the Year Grammy winner in early 1983 was written by Toto keyboard player David Paich, who said it was a composite of several girls he had known. During recording sessions, Toto band members initially played along with the assumption that the song was based on actress Rosanna Arquette, who was dating keyboard player Steve Porcaro at the time. Arquette herself played along with the joke, commenting in an interview that year, “that song was about my showing up at 4 a.m. at the studio to bring them juice and beer.”

“Brandy,” Looking Glass, 1972

Elliot Lurie, guitarist and vocalist for the New Jersey-based group Looking Glass, had been reading old novels when he was inspired to write “Brandy,” a tune about a barmaid in a busy harbor town. Although lonely sailors flirted with her, she instead longed only for a man who left her years earlier because, he claimed, “my life, my lover, my lady, is the sea.” The song quickly moved up the charts to #1 in the summer of 1972, and enjoyed a second life in 2017 when it was used in the soundtrack for “Guardians of The Galaxy Vol. 2.” Interesting note: In 1974, Barry Manilow had to change his song “Brandy” to “Mandy” after the Looking Glass song became a huge hit.

“Emily,” Elton John, 1992

John’s longtime lyricist partner Bernie Taupin penned one of the most poignant character studies in his catalog on this deep track from the 1992 album “The One.” Taupin recalled writing the lyrics to “Emily” after an afternoon walk through the streets and cemeteries of Paris, France, where he couldn’t help but notice an elderly woman paying respects at various gravesites as she walked haltingly among the headstones. “Elton wrote such a glorious melody to accompany this one,” Taupin said. “It’s one of my favorites”: “The old girl hobbles, nylons sagging, talks to her sisters in the ground…”

“Jane,” Jefferson Starship, 1979

Vocalist figurehead Grace Slick had temporarily left the band in 1978 when the Jefferson Starship brought in singer Mickey Thomas for the “Freedom at Point Zero” LP. Bassist David Freiberg wrote most of the music and lyrics for what would become the album’s single, “Jane.” He said, “She’s no one in particular, just the kind of girl who’s insincere and manipulative in the way she behaves in a relationship. I think we’ve all know women — and men — like that”: “You’re playing a game called ‘hard to get’ by its real name, you’re playing a game you can never win, girl…”

“Aubrey,” Bread, 1972

Of the several hit ballads David Gates wrote in the early ’70s as chief songwriter for the soft-rock band Bread, “Aubrey” came across as one of the most sad and heartfelt. One interpretation had it that Aubrey was the name of a baby girl who died at birth; another said she was a woman the narrator was infatuated with but was too shy to approach. In the booklet from Bread’s 2006 anthology collection, Gates said the truth behind “Aubrey” was less interesting — it was inspired by an Audrey Hepburn film he saw but never fully understood. It peaked at #15 in 1973 as the third single from Bread’s fifth LP, “The Guitar Man.”

“Peg,” Steely Dan, 1977

Songwriters Donald Fagen and the late Walter Becker have typically been tight-lipped about the meaning behind their often puzzling lyrics, but Fagen once conceded in an interview that “Peg,” a #11 hit in 1978 from their platinum LP “Aja,” referred to Peg Entwistle, a star of Broadway theater in the 1920s and 1930s. Fagen and Becker found her to be a suitable entry in the Steely Dan cast of offbeat characters because, in 1932, she jumped to her death off the famous Hollywood sign (when it was “Hollywoodland,” an advertisement for a new housing development) before her first film was ever released.

****************************

Honorable mention:

“Michelle,” The Beatles, 1965; “Lucille,” Little Richard, 1957; “Clarice,” America, 1971; “Wendy,” The Beach Boys, 1964; “Valerie,” Steve Winwood, 1982; “Amanda,” Boston, 1983; “Sherry,” The Four Seasons, 1962; “Jessie,” Joshua Kadison, 1992; “Carrie-Anne,” The Hollies, 1967; “Luka,” Suzanne Vega, 1987; “Diana,” Paul Anka, 1958; “Nanci,” Toad the Wet Sprocket, 1994; “Veronica,” Elvis Costello, 1989.

******************************