Woh-whoa, listen to the music

The enjoyment of music is universal, but the ways we have listened to it have evolved considerably over the years.

Our parents/grandparents gathered around the living room radio (the “wireless”) or played 78s on the Victrola. Music lovers in the ’50s put dimes in the jukebox and turned up their transistor radios. By the ’60s,

Our parents/grandparents gathered around the living room radio (the “wireless”) or played 78s on the Victrola. Music lovers in the ’50s put dimes in the jukebox and turned up their transistor radios. By the ’60s,  we still listened incessantly to the car radio and played our stacks of 45s, but we also started buying albums and ever more sophisticated sound systems, including headphones, to listen to our tunes.

we still listened incessantly to the car radio and played our stacks of 45s, but we also started buying albums and ever more sophisticated sound systems, including headphones, to listen to our tunes.

As the 1970s dawned, another huge development occurred that changed everything: Tapes.

At first, there were reel-to-reel tape machines, debuting in the early ’60s, which were pretty much the exclusive domain of audiophiles with deep pockets. They were expensive and cumbersome. You had to fit the big 7″ magnetic tape reels onto spools and feed them past the recording and playback heads. You had to know at least a little bit about setting recording levels, and functions like “rewind” and “fast-forward,” which was way too technical for most people, who left such matters to the nerds in the AV department. But the sound quality (assuming you were using high-quality recording tape) was very good, perhaps as good as the LPs then available. But the market that was interested and affluent enough to invest in this option was a very small niche, largely because (and this is crucial) it wasn’t portable.

At first, there were reel-to-reel tape machines, debuting in the early ’60s, which were pretty much the exclusive domain of audiophiles with deep pockets. They were expensive and cumbersome. You had to fit the big 7″ magnetic tape reels onto spools and feed them past the recording and playback heads. You had to know at least a little bit about setting recording levels, and functions like “rewind” and “fast-forward,” which was way too technical for most people, who left such matters to the nerds in the AV department. But the sound quality (assuming you were using high-quality recording tape) was very good, perhaps as good as the LPs then available. But the market that was interested and affluent enough to invest in this option was a very small niche, largely because (and this is crucial) it wasn’t portable.

Then the cassette tape arrived, which provided the crucial elements of convenience and portability, but the sound quality was pathetic. If you were listening to spoken dialog or nursery rhymes, the cassette adequately served its purpose, and consequently, it was more often used for dictation or as a children’s diversion. But for teens and adults eager to listen to their favorite music, it was simply not an acceptable option — yet.

Then the cassette tape arrived, which provided the crucial elements of convenience and portability, but the sound quality was pathetic. If you were listening to spoken dialog or nursery rhymes, the cassette adequately served its purpose, and consequently, it was more often used for dictation or as a children’s diversion. But for teens and adults eager to listen to their favorite music, it was simply not an acceptable option — yet.

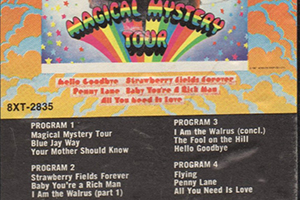

Enter the notorious 8-track tape. The sound quality on these boxy contraptions wasn’t up to the standards of reel-to-reel (or albums), but it was a significant improvement over cassettes. Most important, they too were portable, and in a culture where people spent more and more time in their cars, this was a very big deal. You could still tune in to disc jockeys broadcasting songs on the radio, but now, instead, you could control what you were listening to. For a while, the 8-track tape was hugely popular, and every pickup truck and hot rod on every highway and back road across the country came equipped with an 8-track tape player, first installed as an aftermarket accessory and eventually included in-dash by the auto manufacturers.

Enter the notorious 8-track tape. The sound quality on these boxy contraptions wasn’t up to the standards of reel-to-reel (or albums), but it was a significant improvement over cassettes. Most important, they too were portable, and in a culture where people spent more and more time in their cars, this was a very big deal. You could still tune in to disc jockeys broadcasting songs on the radio, but now, instead, you could control what you were listening to. For a while, the 8-track tape was hugely popular, and every pickup truck and hot rod on every highway and back road across the country came equipped with an 8-track tape player, first installed as an aftermarket accessory and eventually included in-dash by the auto manufacturers.

But 8-tracks had a glaringly frustrating limitation. They were designed with four “programs” which divided the tape’s bandwidth into four sections, and the songs were arranged on those four sections in whatever order fit best. This occasionally required the recording labels to alter the order of the songs from the order found on the album, which messed with the artist’s original creative intent. Sometimes you’d have to endure this scenario: A longer track (and there were plenty that ran as long as 12-15 minutes or more) wouldn’t fit on one program, so it would fade out halfway through, the machine would take as long as 30 seconds to switch to the next program, and the song would then fade back in for its

But 8-tracks had a glaringly frustrating limitation. They were designed with four “programs” which divided the tape’s bandwidth into four sections, and the songs were arranged on those four sections in whatever order fit best. This occasionally required the recording labels to alter the order of the songs from the order found on the album, which messed with the artist’s original creative intent. Sometimes you’d have to endure this scenario: A longer track (and there were plenty that ran as long as 12-15 minutes or more) wouldn’t fit on one program, so it would fade out halfway through, the machine would take as long as 30 seconds to switch to the next program, and the song would then fade back in for its  conclusion. It was incredibly annoying, and there was nothing you could do about it. And there was another problem: At home on your record player, you could lift the needle and repeat a favorite song or skip crummy tracks at will, but 8-track players had no rewind or fast-forward functions and offered no such flexibility. Listeners were essentially prisoners.

conclusion. It was incredibly annoying, and there was nothing you could do about it. And there was another problem: At home on your record player, you could lift the needle and repeat a favorite song or skip crummy tracks at will, but 8-track players had no rewind or fast-forward functions and offered no such flexibility. Listeners were essentially prisoners.

A white knight named Thomas Dolby arrived with his Dolby Noise Reduction System,  which removed or sharply reduced the annoying hiss inherent in early cassette tape sound reproduction technology. This invention, and the introduction of longer-lasting, higher-quality chromium dioxide tape, made cassettes a far more attractive alternative — the convenience and portability of an 8-track with the sound quality approaching that of a reel-to-reel (not to mention its rewind and fast-forward functions). Cassette tape players soon became key components in home stereo systems and the default systems in cars as well, and cassettes eventually rivaled albums at the checkout line.

which removed or sharply reduced the annoying hiss inherent in early cassette tape sound reproduction technology. This invention, and the introduction of longer-lasting, higher-quality chromium dioxide tape, made cassettes a far more attractive alternative — the convenience and portability of an 8-track with the sound quality approaching that of a reel-to-reel (not to mention its rewind and fast-forward functions). Cassette tape players soon became key components in home stereo systems and the default systems in cars as well, and cassettes eventually rivaled albums at the checkout line.

But the most critical development was the debut of blank tape and cassette decks that not only played music but recorded it. Consumers could now not only copy their album collections onto blank cassettes for playback in the car, they could compile their own  mixed tapes of songs from various sources. We could now become de facto disc jockeys ourselves, playing pre-recorded collections of the best songs from our favorite albums, or our friends’ borrowed albums. It was like listening to our own personal radio station with no commercials or chatter, and we got to pick the songs.

mixed tapes of songs from various sources. We could now become de facto disc jockeys ourselves, playing pre-recorded collections of the best songs from our favorite albums, or our friends’ borrowed albums. It was like listening to our own personal radio station with no commercials or chatter, and we got to pick the songs.

Among my circle of friends, I had a reputation as a music lover with an enviable collection and a talent for assembling some excellent mixed tapes, if I do say so myself. It was a labor of love, selecting the right combination of songs. I would listen as I worked, trying to come up with the perfect segue from one song to the next. Sometimes, I would start taping a song and then decide, no, that one didn’t quite mesh as well as I thought it would, so I’d go back and record a different, better song over it. Working with tapes gave me that kind of flexibility.

I’m proud to say my “Hack Tapes” were in high demand at parties, they were frequently borrowed for long road trips, and they were even duplicated if someone owned a “dubbing deck” to make taped copies of tapes.

It was an entirely new arena to express creativity. A mixed tape might contain an exhilarating potpourri of styles, much like the Top 40 playlists of that era might include back-to-back samples of Motown, bubblegum, psychedelia, country, rockabilly and British blues. Or it could feature a concentrated focus on one style — say, ’50s oldies for use at an Elvis revival, or ’70s progressive rock for your next stoner gathering, or reggae and surf music for a pool party. You could also assemble your favorite band’s best songs (and not just the pre-determined “greatest hits”) in a playing order that suited your individual tastes.

It was an entirely new arena to express creativity. A mixed tape might contain an exhilarating potpourri of styles, much like the Top 40 playlists of that era might include back-to-back samples of Motown, bubblegum, psychedelia, country, rockabilly and British blues. Or it could feature a concentrated focus on one style — say, ’50s oldies for use at an Elvis revival, or ’70s progressive rock for your next stoner gathering, or reggae and surf music for a pool party. You could also assemble your favorite band’s best songs (and not just the pre-determined “greatest hits”) in a playing order that suited your individual tastes.

I was fond of making “theme tapes” that brought together songs that shared a common element. For example:

“Rock Around the World” included songs with cities or countries in the title (“Carolina In My Mind” by James Taylor, “I Go to Rio” by Pablo Cruise, “London Calling” by The Clash, “The Only Living Boy in New York” by Simon and Garfunkel).

“On the Road Again” featured tunes about cars and driving (“Little Deuce Coupe” by The Beach Boys, “Rockin’ Down the Highway” by The Doobie Brothers, “Thunder Road” by Bruce Springsteen, “Little Red Corvette” by Prince).

“Catch That Buzz” focused on numbers about drinking and partying (“One Scotch, One Bourbon, One Beer” by George Thorogood, “Tequila” by The Champs, “Margaritaville” by Jimmy Buffett, “Shanty” by Jonathan Edwards)

“Wake Up Tape” had songs with “Morning” in the title (“Chelsea Morning” by Joni Mitchell, “Morning Has Broken” by Cat Stevens, “One Fine Morning” by Lighthouse, “Good Morning Good Morning” by The Beatles).

“Stormy Weather” included tracks about rain (“Let It Rain” by Eric Clapton, “Riders on the Storm” by The Doors, “Walk Between Raindrops” by Donald Fagen, “Early Morning Rain” by Gordon Lightfoot).

For the altruist, the mixed tape also offered a perfect opportunity to compile the favorite songs of a friend or loved one and wrap it up as a very personal kind of birthday present. For many Christmases, I gave my sister “Best Of” collections of songs from 30 or 40 years earlier (“Best of 1969” in 1999, etc.), which are not only fun for her to listen to, but fun for me to make. One day a friend and I had a wonderfully spirited discussion about what might have happened if The Beatles had stayed together another year or two longer, and all the early solo hits were merged into one great final Beatles album. Two days later, I handed him a copy of my new mix, “The Lost Beatles Album,” which included everything from “My Sweet Lord” and “Imagine” and “It Don’t Come Easy” to deep tracks like “Let It Roll,” “The Back Seat of My Car” and “Working Class Hero.” I cherished the creative process as well as the finished product.

For the altruist, the mixed tape also offered a perfect opportunity to compile the favorite songs of a friend or loved one and wrap it up as a very personal kind of birthday present. For many Christmases, I gave my sister “Best Of” collections of songs from 30 or 40 years earlier (“Best of 1969” in 1999, etc.), which are not only fun for her to listen to, but fun for me to make. One day a friend and I had a wonderfully spirited discussion about what might have happened if The Beatles had stayed together another year or two longer, and all the early solo hits were merged into one great final Beatles album. Two days later, I handed him a copy of my new mix, “The Lost Beatles Album,” which included everything from “My Sweet Lord” and “Imagine” and “It Don’t Come Easy” to deep tracks like “Let It Roll,” “The Back Seat of My Car” and “Working Class Hero.” I cherished the creative process as well as the finished product.

The point is, blank cassettes gave you a freedom, previously unattainable, to listen to what you wanted when you wanted where you wanted. It was a music lover’s utopia, made even better in the early ’80s with the debut of the Sony Walkman and the “boom box,” which broadened the “where” horizons even further.

The point is, blank cassettes gave you a freedom, previously unattainable, to listen to what you wanted when you wanted where you wanted. It was a music lover’s utopia, made even better in the early ’80s with the debut of the Sony Walkman and the “boom box,” which broadened the “where” horizons even further.

With the advent of the compact disc in the ’80s (or more accurately, the recordable blank CD in the ’90s), the mixed  collection could now be assembled on CD as well. And these days, since the arrival of iTunes libraries and digital downloads, assembling a CD mix can be accomplished in a fraction of the time just by clicking on 15-20 files and then walking away. But I’m something of a dinosaur who clings to the old way of doing things, and I can’t help but be saddened by this “improvement.” The process seems to be more practical and less emotional, more lazy and less personally committed. Sure, it’s more convenient — you can even just hit “shuffle” and have your songs played back in random order. But there’s no heart and soul in that. The creativity required to compile a truly memorable mixed tape/CD — coming up with an appropriate theme, just the right order, the perfect segue — seems to be mostly lost these days.

collection could now be assembled on CD as well. And these days, since the arrival of iTunes libraries and digital downloads, assembling a CD mix can be accomplished in a fraction of the time just by clicking on 15-20 files and then walking away. But I’m something of a dinosaur who clings to the old way of doing things, and I can’t help but be saddened by this “improvement.” The process seems to be more practical and less emotional, more lazy and less personally committed. Sure, it’s more convenient — you can even just hit “shuffle” and have your songs played back in random order. But there’s no heart and soul in that. The creativity required to compile a truly memorable mixed tape/CD — coming up with an appropriate theme, just the right order, the perfect segue — seems to be mostly lost these days.

I still have (in storage) the cassettes I made between 1975 and 2005, and although I don’t play them because I no longer have a tape player in my car or my home, I’ve converted many of them to CD format, and I play those all the time. And I still make CD mixes now and then, and I put a lot of thought into them as I build them. So there’s hope that the  old ways may yet have life, if the rebirth of vinyl and turntables among the hardcore audiophiles is any indication. Once disparaged as “old school,” LPs are now recognized as the gold standard for their superior audio quality. As they say, everything truly great, given time, comes back into fashion eventually.

old ways may yet have life, if the rebirth of vinyl and turntables among the hardcore audiophiles is any indication. Once disparaged as “old school,” LPs are now recognized as the gold standard for their superior audio quality. As they say, everything truly great, given time, comes back into fashion eventually.

I still chuckle and get a twinkle in my eye when someone asks me, “Hey Hack, can you make me a mix for Christmas?”

— is predictable. For more than half a century, radio play has typically gone to the songs and artists that cater to the masses. Safe, accessible, painless to interpret and assimilate. Not that there’s anything inherently wrong with that. But like many music aficionados, I tend to prefer art that somehow pushes the boundaries, explores the unusual, juxtaposes disparate elements, and yet wraps it in an aurally pleasing manner that’s memorable and gratifying.

— is predictable. For more than half a century, radio play has typically gone to the songs and artists that cater to the masses. Safe, accessible, painless to interpret and assimilate. Not that there’s anything inherently wrong with that. But like many music aficionados, I tend to prefer art that somehow pushes the boundaries, explores the unusual, juxtaposes disparate elements, and yet wraps it in an aurally pleasing manner that’s memorable and gratifying.