If I really say it, the radio won’t play it

Boldly creative art has been facing censorship for centuries, and attempts to stifle provocative popular music lyrics have been going on since the Top 40 Hit Parade debuted way back in the 1930s. Over the years and still true today (although to a far lesser extent), song words have been occasionally bleeped, masked and even outright banned to keep lyrics deemed inappropriate or objectionable from being heard on the public airwaves.

Much as films were heavily censored in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s to remove any scenes or dialog considered by industry watchdogs to be immoral, popular music in the first decades of the rock and roll era often came under the same sort of scrutiny by record company executives and radio programmers.

Much as films were heavily censored in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s to remove any scenes or dialog considered by industry watchdogs to be immoral, popular music in the first decades of the rock and roll era often came under the same sort of scrutiny by record company executives and radio programmers.

Instances of censorship involved different types of objections — profanity, politics, sacrilege, sexual content, drug abuse, even commercial product mentions. Radio programmers typically said they were worried of running afoul of decency laws or offending powerful interests, but more often than not, they were just as concerned about losing revenues from advertisers or local retailers who refused to be associated with a song’s edgy lyrical content.

But what, exactly, is edgy? How do we define it? Standards regarding what is objectionable have changed significantly over 80+ years. This is particularly true when it comes to lyrics about sex. In 1943, for example, a British singer named George Formby found out that his recording of a song called “When I’m Cleaning Windows” was going to be banned from airplay because the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) decided the lyric was “too racy.” Here’s how it went: “The blushing bride she looks divine, the bridegroom he is doing fine, I’d rather have his job than mine, when I’m cleaning windows…” Wow. This innocuous song was banned, evidently, because someone determined we shouldn’t hear lyrics that they thought described a voyeur spying on newlyweds from his perch on the window washing scaffold.

Van Morrison’s beloved 1967 classic “Brown-Eyed Girl” raised eyebrows at the time because of the obvious sexual lyric “making love in the green grass behind the stadium with you” in the third verse. Most stations were reluctant to ban the whole song, so they simply removed that line and replaced it by repeating “laughing and a-running, hey hey” from the first verse, despite Morrison’s heated protestations.

Van Morrison’s beloved 1967 classic “Brown-Eyed Girl” raised eyebrows at the time because of the obvious sexual lyric “making love in the green grass behind the stadium with you” in the third verse. Most stations were reluctant to ban the whole song, so they simply removed that line and replaced it by repeating “laughing and a-running, hey hey” from the first verse, despite Morrison’s heated protestations.

(It’s interesting to note that Morrison had originally written the song about a Caribbean woman and had entitled it “Brown-Skinned Girl,” but the record company refused to release a song that seemed to endorse a mixed-race relationship, so he grudgingly agreed to change it to “Brown-Eyed Girl.”)

By 1987, the George Michael hit “I Want Your Sex” managed to reach #1 that year, but it met enough resistance in a few conservative areas to create the alternate version “I Want Your Love.” And through the years, there has been no shortage of rather graphic sex-oriented lyrics hidden deep on rock albums (check out Frank Zappa’s “Dinah-Moe Humm” from 1973), but they usually slid under the radar because they didn’t get radio play except on the most maverick FM stations.

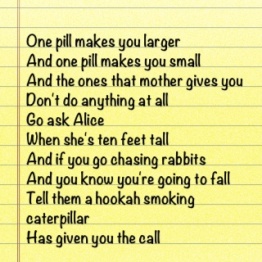

Many songs with references to drug use started in the freewheeling ’60s with tracks like Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit,” which tied the story of “Alice in Wonderland” to hallucinogens. And while John Lennon always maintained the “LSD” initials of The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” was purely coincidental, the song was clearly awash in psychedelic imagery.

Many songs with references to drug use started in the freewheeling ’60s with tracks like Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit,” which tied the story of “Alice in Wonderland” to hallucinogens. And while John Lennon always maintained the “LSD” initials of The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” was purely coincidental, the song was clearly awash in psychedelic imagery.

And there are much earlier examples: Some versions of the 1940s-era Cole Porter standard “I Get a Kick Out of You” were rewritten to remove the second verse — “Some, they may go for cocaine, I’m sure that if I took even one sniff, it would bore me terrifically too, yet I get a kick out of you” — because censors feared it would glamourize drug use (even though it’s clear the singer didn’t even try the stuff!).

While drug-oriented lyrics abound on many album tracks of rock LPs, if they show up in the hit singles, they’re usually subject to some sort of censorship. Tom Petty’s 1994 song “You Don’t Know How It Feels” includes the line, “Let’s get to the point, let’s roll another joint,” a blatant marijuana reference that was intentionally garbled by many radio stations.

Sometimes the censors were totally off-base, interpreting an innocent children’s fairy tale like Peter, Paul & Mary’s “Puff the Magic Dragon” as a veiled reference to smoking weed. “Oh, for crying out loud,” said Peter Yarrow in 1963 when the song was released. “It’s just a children’s song, a story about a boy and a dragon.” But some stations in conservative areas blackballed it anyway, at least for a while.

Sometimes the censors were totally off-base, interpreting an innocent children’s fairy tale like Peter, Paul & Mary’s “Puff the Magic Dragon” as a veiled reference to smoking weed. “Oh, for crying out loud,” said Peter Yarrow in 1963 when the song was released. “It’s just a children’s song, a story about a boy and a dragon.” But some stations in conservative areas blackballed it anyway, at least for a while.

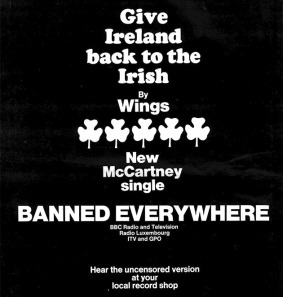

Overt political views were sometimes deemed too controversial for radio play. Barry McGuire’s antiwar song “Eve of Destruction” (1965) made waves because of the line ‘they’re old enough to kill but not for votin’.” The Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen” (1976) and Paul  McCartney’s “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” (1972) were banned from the BBC for their perceived anti-government opinions.

McCartney’s “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” (1972) were banned from the BBC for their perceived anti-government opinions.

Stations squeamish about offending religious groups took issue with The Beatles’ “The Ballad of John and Yoko” (1969), which was bleeped in most Bible Belt markets each time Lennon sang, “Christ! You know it ain’t easy…” Producers of the rock opera “Jesus Christ Superstar” had to battle mightily for a while to get the title track played in some communities that assumed it was blasphemous. The Charlie Daniels Band’s “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” (1979) met resistance too — not because of Satan (who loses the fiddle duel, after all), but with the line “I told you once, you son of a bitch,” which was changed to “son of a gun” in some markets.

The Who’s “My Generation” (1965), with its stuttering vocals, was thought by some to be offensive to those with speech impediments. Dire Straits’ “Money for Nothing” (1985) faced a fight regarding what many considered a defamatory remark against gays in the second verse — “that little faggot is a millionaire” — even though composer Mark Knopfler pointed out he was belittling the small-minded thinking of the character who spoke the line. In these cases, the bans didn’t last more than a week or so, but it’s interesting to note that objections were raised at all.

The BBC even had a firm rule against any commercial product placement in song lyrics, which caused problems for Paul Simon’s hit “Kodachrome” (1973). The Kinks’ singer Ray Davies had to return to a London studio to re-record a vocal part for the 1970 hit “Lola,” revising the lyric from Coca-Cola to cherry cola.

The BBC even had a firm rule against any commercial product placement in song lyrics, which caused problems for Paul Simon’s hit “Kodachrome” (1973). The Kinks’ singer Ray Davies had to return to a London studio to re-record a vocal part for the 1970 hit “Lola,” revising the lyric from Coca-Cola to cherry cola.

For years, “The Ed Sullivan Show” ruled supreme as the arbiter of which rock ‘n roll groups were worthy of nationwide TV exposure, beginning with Elvis in 1956 and up through the game-changing Beatles performances in early 1964. But Sullivan reserved the right to approve all material, and in 1967, he rolled the dice twice by inviting two  edgier acts to appear. First he booked those bad British brats, The Rolling Stones, and demanded that their brash young singer, Mick Jagger, change the words of “Let’s Spend the Night Together” to “Let’s Spend Some Time Together.” Jagger went along, but rolled his eyes at the camera each time he sang it.

edgier acts to appear. First he booked those bad British brats, The Rolling Stones, and demanded that their brash young singer, Mick Jagger, change the words of “Let’s Spend the Night Together” to “Let’s Spend Some Time Together.” Jagger went along, but rolled his eyes at the camera each time he sang it.

Then a month later came Jim Morrison and The Doors, who were forced to alter their #1 hit “Light My Fire” by changing “girl, we couldn’t get much higher” to “girl, we couldn’t get much better” (even though it didn’t rhyme with “liar” and “fire”). Morrison played along during rehearsals, but when the show was taped, he looked defiantly into the camera and sang the real lyric, and Sullivan went through the roof, canceling all future appearances by the group.

The main problem with censorship, though, has alway been that it’s arbitrary and uneven in enforcement. Who gets to say what is objectionable? How do we determine the standards? When and where are they enforced? Why do some songs face an embargo or tampering while others skate by without any challenges?

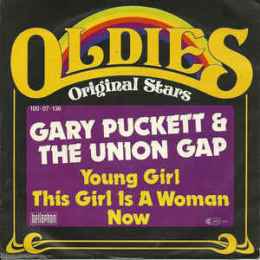

A couple of Gary Puckett songs in the late ’60s — “Young Girl,” “This Girl is a Woman Now” — focused on a creepy infatuation of a young girl by an older guy that, looking at it now, clearly bordered on pedophilia, but they somehow escaped the censors’ attention at the time. Even more curious was the case of The Buoys, a one-hit wonder group who had the sheer chutzpah to release a single in 1971 called “Timothy” that told the disturbing tale of three poor souls who were trapped in a caved-in mine, and two of the boys ate the third boy in order to survive!

A couple of Gary Puckett songs in the late ’60s — “Young Girl,” “This Girl is a Woman Now” — focused on a creepy infatuation of a young girl by an older guy that, looking at it now, clearly bordered on pedophilia, but they somehow escaped the censors’ attention at the time. Even more curious was the case of The Buoys, a one-hit wonder group who had the sheer chutzpah to release a single in 1971 called “Timothy” that told the disturbing tale of three poor souls who were trapped in a caved-in mine, and two of the boys ate the third boy in order to survive!

The hypocrisy and randomness of the censors’ actions was puzzling, to say the least. Having sex in the grass? No way, Jose. Cannibalism? Hey, no problem. Share a little weed? Not on your life. Interest in underage girls? Oh, that’s okay.

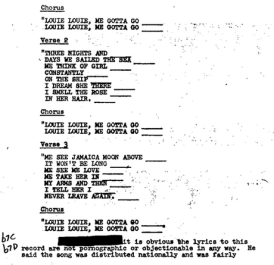

Perhaps the most extreme response to a supposedly objectionable lyric came in 1963 when a team of agents from J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI spent months investigating whether the words to The Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie” were obscene. Teens had furtively talked about how the lyrics were allegedly about a sexual liaison, but in fact, the song (written in 1957) was a rather bland ode from a sailor to his girl back home. Thanks to a marble-mouthed vocalist and less-than-optimum recording techniques, the words were pretty much impossible to decipher, even when studied at different speeds under headphones, and the FBI eventually threw up their hands.

Perhaps the most extreme response to a supposedly objectionable lyric came in 1963 when a team of agents from J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI spent months investigating whether the words to The Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie” were obscene. Teens had furtively talked about how the lyrics were allegedly about a sexual liaison, but in fact, the song (written in 1957) was a rather bland ode from a sailor to his girl back home. Thanks to a marble-mouthed vocalist and less-than-optimum recording techniques, the words were pretty much impossible to decipher, even when studied at different speeds under headphones, and the FBI eventually threw up their hands.

But that was then, this is now. In 2010, R&B artist CeeLo Green had an enormous hit with a song called, believe it or not, “F–k You.” They released a cleaned-up version called “Forget You” to satisfy radio programmers, but most listeners, to no one’s surprise, preferred the original.

But that was then, this is now. In 2010, R&B artist CeeLo Green had an enormous hit with a song called, believe it or not, “F–k You.” They released a cleaned-up version called “Forget You” to satisfy radio programmers, but most listeners, to no one’s surprise, preferred the original.

The times they are a-changin’, indeed…

Fortunately, many of these great “lost classics” are available today to those who didn’t hang on to their old records, or are too young to have been exposed to them in the first place. Online music services provide a wealth of decades-old music — in fact, so much of it that you can be overwhelmed. Where to start?

Fortunately, many of these great “lost classics” are available today to those who didn’t hang on to their old records, or are too young to have been exposed to them in the first place. Online music services provide a wealth of decades-old music — in fact, so much of it that you can be overwhelmed. Where to start? Musical wunderkind Steve Winwood and drummer Jim Capaldi formed Traffic as a quasi folk-jazz-rock hybrid outfit in 1967, with Dave Mason on guitar and Chris Wood on flute. They earned praise in England for their first two records, but Mason soon left and Winwood spent several months in the hugely hyped side project called Blind Faith with his friend Eric Clapton. Winwood then intended on unveiling his first solo LP but it turned into the reformation of Traffic (without Mason) and became the brilliant 1970 album “John Barleycorn Must Die.” By 1971, the group chose to broaden its sound by adding Blind Faith’s Ric Grech on bass and violin, Derek and the Dominos’ Jim Gordon on drums and Rebop Kwaku Baah on percussion, and the result was their best selling album in the US, “The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys.” The epic, haunting title tune justifiably got most of the attention, but another solid deep track not to be ignored is “Many a Mile to Freedom,” a delicious piece Winwood co-wrote with Jim Capaldi’s wife Anna that’s peppered with Chris Wood’s fine flute work and carried by Winwood’s top-flight vocals.

Musical wunderkind Steve Winwood and drummer Jim Capaldi formed Traffic as a quasi folk-jazz-rock hybrid outfit in 1967, with Dave Mason on guitar and Chris Wood on flute. They earned praise in England for their first two records, but Mason soon left and Winwood spent several months in the hugely hyped side project called Blind Faith with his friend Eric Clapton. Winwood then intended on unveiling his first solo LP but it turned into the reformation of Traffic (without Mason) and became the brilliant 1970 album “John Barleycorn Must Die.” By 1971, the group chose to broaden its sound by adding Blind Faith’s Ric Grech on bass and violin, Derek and the Dominos’ Jim Gordon on drums and Rebop Kwaku Baah on percussion, and the result was their best selling album in the US, “The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys.” The epic, haunting title tune justifiably got most of the attention, but another solid deep track not to be ignored is “Many a Mile to Freedom,” a delicious piece Winwood co-wrote with Jim Capaldi’s wife Anna that’s peppered with Chris Wood’s fine flute work and carried by Winwood’s top-flight vocals. Renaissance was born in 1969 when two ex-Yardbirds (Jim McCarty and Keith Relf) had tired of blues-based rock and wanted to experiment with a blend of classical, rock and folk forms. A revolving door of musicians came and went as the group struggled during their first three years, but eventually Renaissance found a solid core revolving around the astonishing four-octave voice of Annie Haslam and the accomplished piano playing of John Tout. With guitarist Michael Dunford and poet/lyricist Betty Thatcher-Newsinger collaborating on the composing duties, Renaissance began its rise in popularity, with albums like “Prologue” and “Ashes are Burning” getting airplay in Northeast US cities like Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York and Boston. The 1974 album “Turn of the Cards” displayed a more dark, lush, orchestral sound, and that showed up most noticeably on the superb, nine-minute opening track, “Running Hard.” The group’s successful hybrid of classical music, folk and rock served them well for another three LPs (“Scheherazade,” “Novella” and “A Song For All Seasons”) before dissolving in the mid-’80s.

Renaissance was born in 1969 when two ex-Yardbirds (Jim McCarty and Keith Relf) had tired of blues-based rock and wanted to experiment with a blend of classical, rock and folk forms. A revolving door of musicians came and went as the group struggled during their first three years, but eventually Renaissance found a solid core revolving around the astonishing four-octave voice of Annie Haslam and the accomplished piano playing of John Tout. With guitarist Michael Dunford and poet/lyricist Betty Thatcher-Newsinger collaborating on the composing duties, Renaissance began its rise in popularity, with albums like “Prologue” and “Ashes are Burning” getting airplay in Northeast US cities like Cleveland, Philadelphia, New York and Boston. The 1974 album “Turn of the Cards” displayed a more dark, lush, orchestral sound, and that showed up most noticeably on the superb, nine-minute opening track, “Running Hard.” The group’s successful hybrid of classical music, folk and rock served them well for another three LPs (“Scheherazade,” “Novella” and “A Song For All Seasons”) before dissolving in the mid-’80s. The impressive run of seven albums that established The Moodies as pioneers of the burgeoning progressive rock genre are a veritable treasure trove of lost classics. From 1967’s “Days of Future Passed” through 1972’s “Seventh Sojourn,” for every hit single you instantly recognize (“Ride My Seesaw,” “The Story in Your Eyes,” “I’m Just a Singer in a Rock and Roll Band”) you’ll find another five or six songs well worth checking out. The group boasted five musicians who each brought something intriguing to the mix, from Ray Thomas’s flute to Graeme Edge’s gentle poem-songs, from John Lodge’s rocking bass to Mike Pinder’s Mellotron/keyboard pieces. The most recognizable element of The Moodies’ sound, though, has always been the vocals and melodic songs of guitarist Justin Hayward. On the band’s 1970 LP “A Question of Balance,” you can hear his work most prominently on the hit “Question” and the excellent “It’s Up to You.” Hidden on side two (remember album sides?) is another Hayward beauty, “Dawning is the Day.”

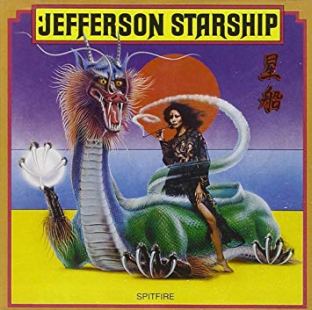

The impressive run of seven albums that established The Moodies as pioneers of the burgeoning progressive rock genre are a veritable treasure trove of lost classics. From 1967’s “Days of Future Passed” through 1972’s “Seventh Sojourn,” for every hit single you instantly recognize (“Ride My Seesaw,” “The Story in Your Eyes,” “I’m Just a Singer in a Rock and Roll Band”) you’ll find another five or six songs well worth checking out. The group boasted five musicians who each brought something intriguing to the mix, from Ray Thomas’s flute to Graeme Edge’s gentle poem-songs, from John Lodge’s rocking bass to Mike Pinder’s Mellotron/keyboard pieces. The most recognizable element of The Moodies’ sound, though, has always been the vocals and melodic songs of guitarist Justin Hayward. On the band’s 1970 LP “A Question of Balance,” you can hear his work most prominently on the hit “Question” and the excellent “It’s Up to You.” Hidden on side two (remember album sides?) is another Hayward beauty, “Dawning is the Day.” The Jefferson Airplane didn’t so much crash and burn as peter out, but founder Paul Kantner always had his eye on reimagining the Jefferson name to further explore his passion for science fiction and fantasy. First came his solo LP “Blows Against the Empire” in 1970, where the loose crew of musicians who participated was first referred to as Jefferson Starship. On the 1974 LP “Dragonfly,” with guitarist Craig Chaquico, bassist Pete Sears, keyboardist David Freiberg, violinist Papa John Kreach and drummer Johnny Barbata joining Kantner and rock icon Grace Slick, Jefferson Starship was officially launched with stellar material like “Ride the Tiger,” “All Fly Away” and “Caroline.” Airplane founder Marty Balin joined the lineup full-time on the #1 LP “Red Octopus” in 1975, which included the huge hit single “Miracles.” The band played to sold-out arenas in 1976 when it toured in support of the follow-up LP, “Spitfire.” My favorite track from that LP is the soaring “St. Charles,” featuring the vocal blend of Kantner and Slick.

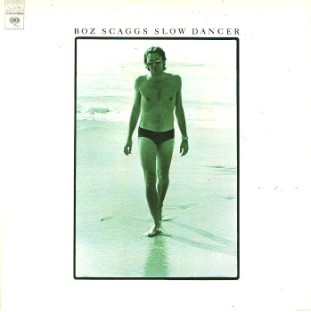

The Jefferson Airplane didn’t so much crash and burn as peter out, but founder Paul Kantner always had his eye on reimagining the Jefferson name to further explore his passion for science fiction and fantasy. First came his solo LP “Blows Against the Empire” in 1970, where the loose crew of musicians who participated was first referred to as Jefferson Starship. On the 1974 LP “Dragonfly,” with guitarist Craig Chaquico, bassist Pete Sears, keyboardist David Freiberg, violinist Papa John Kreach and drummer Johnny Barbata joining Kantner and rock icon Grace Slick, Jefferson Starship was officially launched with stellar material like “Ride the Tiger,” “All Fly Away” and “Caroline.” Airplane founder Marty Balin joined the lineup full-time on the #1 LP “Red Octopus” in 1975, which included the huge hit single “Miracles.” The band played to sold-out arenas in 1976 when it toured in support of the follow-up LP, “Spitfire.” My favorite track from that LP is the soaring “St. Charles,” featuring the vocal blend of Kantner and Slick. Scaggs got his start in the late ’60s as a guitarist in San Francisco as part of the original lineup of the Steve Miller Band, and by 1969, he was testing the waters with a self-titled solo LP that included the incredible “Loan Me a Dime” with Duane Allman guesting on lead guitar. It wasn’t until 1976 when he had his commercial breakthrough with the outstanding “Silk Degrees” LP, a catchy collection of slick “blue-eyed soul” that got plenty of airplay (particularly “It’s Over,” “What Can I Say,” “Lido Shuffle” and the #3 hit “Lowdown”) in the age of disco’s rise in popularity. Before that fame arrived, Scaggs released a strong but overlooked album of R&B-laced songs in 1974 called “Slow Dancer,” produced by Motown great Johnny Bristol. “You Make It So Hard to Say No” and “Pain of Love” have Bristol’s soul imprint on them, but the finest moment here is “Angel Lady (Come Just in Time),” which compels you to get up and dance to its mid-tempo groove.

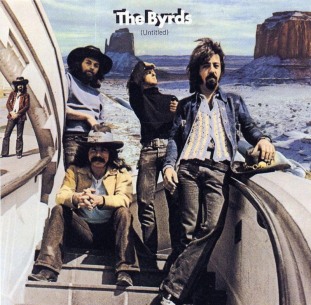

Scaggs got his start in the late ’60s as a guitarist in San Francisco as part of the original lineup of the Steve Miller Band, and by 1969, he was testing the waters with a self-titled solo LP that included the incredible “Loan Me a Dime” with Duane Allman guesting on lead guitar. It wasn’t until 1976 when he had his commercial breakthrough with the outstanding “Silk Degrees” LP, a catchy collection of slick “blue-eyed soul” that got plenty of airplay (particularly “It’s Over,” “What Can I Say,” “Lido Shuffle” and the #3 hit “Lowdown”) in the age of disco’s rise in popularity. Before that fame arrived, Scaggs released a strong but overlooked album of R&B-laced songs in 1974 called “Slow Dancer,” produced by Motown great Johnny Bristol. “You Make It So Hard to Say No” and “Pain of Love” have Bristol’s soul imprint on them, but the finest moment here is “Angel Lady (Come Just in Time),” which compels you to get up and dance to its mid-tempo groove. Through every phase of The Byrds’ recording career, it was Roger McGuinn’s plaintive vocals and songs that dominated the proceedings. In 1969, following the pioneering country rock LP “Sweetheart of the Rodeo,” McGuinn began a collaboration with Broadway impresario Jacques Levy for a country-rock stage production of Henrik Ibsen’s “Peer Gynt,” to be entitled “Gene Tryp” (an anagram of the title of Ibsen’s play). Ultimately, the stage production was abandoned, but among the songs that McGuinn and Levy had written for the project, four ended up on the Byrds’ next album, curiously entitled “(Untitled)“ due to a misunderstanding by the record company. It’s a double album, with one live disc and one with new studio tracks. The best one, to my ears, is “Chestnut Mare,” a fine tune about an uncooperative horse who defiantly resists attempts to tame her. McGuinn’s trademark electric 12-string and Clarence White’s country-style acoustic picking dominate the arrangement.

Through every phase of The Byrds’ recording career, it was Roger McGuinn’s plaintive vocals and songs that dominated the proceedings. In 1969, following the pioneering country rock LP “Sweetheart of the Rodeo,” McGuinn began a collaboration with Broadway impresario Jacques Levy for a country-rock stage production of Henrik Ibsen’s “Peer Gynt,” to be entitled “Gene Tryp” (an anagram of the title of Ibsen’s play). Ultimately, the stage production was abandoned, but among the songs that McGuinn and Levy had written for the project, four ended up on the Byrds’ next album, curiously entitled “(Untitled)“ due to a misunderstanding by the record company. It’s a double album, with one live disc and one with new studio tracks. The best one, to my ears, is “Chestnut Mare,” a fine tune about an uncooperative horse who defiantly resists attempts to tame her. McGuinn’s trademark electric 12-string and Clarence White’s country-style acoustic picking dominate the arrangement. Many people may not be aware that Jim Messina was a staff producer at Columbia Records in 1970 when he was brought in to help mold an untested new talent named Kenny Loggins. Messina contributed so much to Loggins’ debut (songwriting, singing, playing, arranging and producing) that it ended up being called “Kenny Loggins with Jim Messina Sittin’ In.” That, in turn, resulted in the two men officially embarking on a six-year career as a duo, marked by five successful studio LPs, two live albums and a huge hit single (“Your Mama Don’t Dance”). There’s so much great material to be found there, but I want to focus on “Pretty Princess,” a brilliant track from their final LP, “Native Sons.” I’ve always been very fond of it, not as much for its musical beauty as for its lyrics, which tell a story that seemed to closely mirror a relationship I had shortly after the album’s release. A man and a woman who had been merely friends found themselves growing into much more than that, despite the fact that she was beholden to someone else.

Many people may not be aware that Jim Messina was a staff producer at Columbia Records in 1970 when he was brought in to help mold an untested new talent named Kenny Loggins. Messina contributed so much to Loggins’ debut (songwriting, singing, playing, arranging and producing) that it ended up being called “Kenny Loggins with Jim Messina Sittin’ In.” That, in turn, resulted in the two men officially embarking on a six-year career as a duo, marked by five successful studio LPs, two live albums and a huge hit single (“Your Mama Don’t Dance”). There’s so much great material to be found there, but I want to focus on “Pretty Princess,” a brilliant track from their final LP, “Native Sons.” I’ve always been very fond of it, not as much for its musical beauty as for its lyrics, which tell a story that seemed to closely mirror a relationship I had shortly after the album’s release. A man and a woman who had been merely friends found themselves growing into much more than that, despite the fact that she was beholden to someone else. Waits, with his gravelly voice and gritty songs about the underbelly of American society, has been around now for many decades but has never seen much in the way of sales or chart success. He has a loyal cult following and has been widely admired by all kinds of musical icons like Bob Dylan and the late David Bowie. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2011 and is on Rolling Stone’s list of the 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time. If you know nothing about Waits or his music, I urge you to spend some time perusing his catalog, and I would start with the album that started him on his way, the 1973 debut called “Closing Time.” This is an album I love to put on when it’s a cold and rainy Sunday afternoon and I’m feeling a bit blue. It’s hard to pick a favorite here, but I guess I’ll go with “Rosie,” full of angst and raw emotion about the girl who got away.

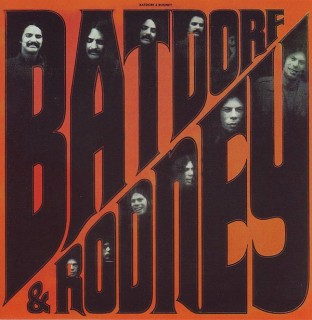

Waits, with his gravelly voice and gritty songs about the underbelly of American society, has been around now for many decades but has never seen much in the way of sales or chart success. He has a loyal cult following and has been widely admired by all kinds of musical icons like Bob Dylan and the late David Bowie. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2011 and is on Rolling Stone’s list of the 100 Greatest Songwriters of All Time. If you know nothing about Waits or his music, I urge you to spend some time perusing his catalog, and I would start with the album that started him on his way, the 1973 debut called “Closing Time.” This is an album I love to put on when it’s a cold and rainy Sunday afternoon and I’m feeling a bit blue. It’s hard to pick a favorite here, but I guess I’ll go with “Rosie,” full of angst and raw emotion about the girl who got away. At the top my list of artists who should have been rewarded with much more commercial success is this duo of singer-guitarist talents. John Batdorf wrote and sang most of the songs that appear on their two exemplary Atlantic LPs, 1971’s “Off the Shelf” and 1972’s “Batdorf and Rodney.” Rodney provided the jazzy acoustic lead parts and chipped in on backing harmonies as well. They were shepherded along by Atlantic guru Ahmet Ertegun, which makes their chart disappointment all the more puzzling. Personally, I’d take the music of Batdorf and Rodney over many of the more commercially successful acts of that era. “Can You See Him,” “Oh My Surprise,” “By Today,” “You Are the One,” “Home Again” — all of these tunes eclipse most of the work by Seals and Crofts or Bread, just to name two. I’m particularly partial to “All I Need,” a thoughtful song from the second album.

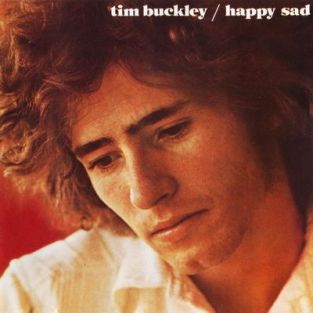

At the top my list of artists who should have been rewarded with much more commercial success is this duo of singer-guitarist talents. John Batdorf wrote and sang most of the songs that appear on their two exemplary Atlantic LPs, 1971’s “Off the Shelf” and 1972’s “Batdorf and Rodney.” Rodney provided the jazzy acoustic lead parts and chipped in on backing harmonies as well. They were shepherded along by Atlantic guru Ahmet Ertegun, which makes their chart disappointment all the more puzzling. Personally, I’d take the music of Batdorf and Rodney over many of the more commercially successful acts of that era. “Can You See Him,” “Oh My Surprise,” “By Today,” “You Are the One,” “Home Again” — all of these tunes eclipse most of the work by Seals and Crofts or Bread, just to name two. I’m particularly partial to “All I Need,” a thoughtful song from the second album. Born in New York state but raised in California, Tim Buckley was a singer-songwriter maverick, never fully comfortable with his talents nor the various genres with which he continually experimented. His self-titled debut in 1966 and 1967 follow-up effort, “Goodbye and Hello,” showcased his early folk leanings, but for me, his best work can be found on the 1969 LP “Happy Sad,” which marked the beginning of his forays into jazz elements and freeform scat singing. The 12-minute track “Gypsy Woman,” which became a mainstay of his live performances, is the best example of that style, which would become more pervasive over his next several albums, even though it seemed to alienate his original fan base. Buckley’s recorded apex, in my view, is the dreamy “Buzzin’ Fly,” highlighted by the unusual vibraphone sounds of David Friedman and his friend Lee Underwood’s guitar. Buckley died of a drug overdose in 1975. His son Jeff was a highly acclaimed singer-songwriter too, until his drowning death in 1997.

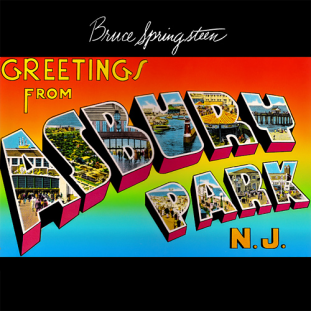

Born in New York state but raised in California, Tim Buckley was a singer-songwriter maverick, never fully comfortable with his talents nor the various genres with which he continually experimented. His self-titled debut in 1966 and 1967 follow-up effort, “Goodbye and Hello,” showcased his early folk leanings, but for me, his best work can be found on the 1969 LP “Happy Sad,” which marked the beginning of his forays into jazz elements and freeform scat singing. The 12-minute track “Gypsy Woman,” which became a mainstay of his live performances, is the best example of that style, which would become more pervasive over his next several albums, even though it seemed to alienate his original fan base. Buckley’s recorded apex, in my view, is the dreamy “Buzzin’ Fly,” highlighted by the unusual vibraphone sounds of David Friedman and his friend Lee Underwood’s guitar. Buckley died of a drug overdose in 1975. His son Jeff was a highly acclaimed singer-songwriter too, until his drowning death in 1997. Before there was an E Street Band, Bruce Springsteen was signed by Columbia Records honcho John Hammond as a solo artist, in the Bob Dylan mold, largely because Springsteen’s earliest songs likewise featured an overabundance of lyrics, delivered over lively acoustic tunes. Although he had his eye on becoming an all-out rocker with a full band, Springsteen relented and allowed his debut LP, “Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J.,” to feature more subdued material like “Mary, Queen of Arkansas” and “The Angel.” In turn, Hammond gave in and permitted Bruce to record two uptempo tracks — “Blinded By the Light” and “Spirits in the Night” — that included sax man Clarence Clemons and the rest of the soon-to-be E Street Band. Riding the balance between these two approaches were the three songs I admire most, which became staples in his live repertoire for the next few years: “Growin’ Up,” “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City” and the piano-based “For You,” which was often played at a much slower tempo in concert.

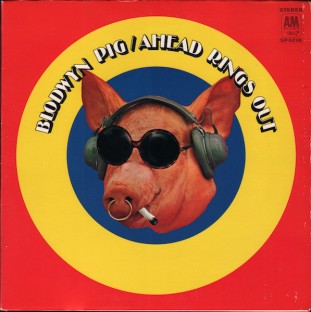

Before there was an E Street Band, Bruce Springsteen was signed by Columbia Records honcho John Hammond as a solo artist, in the Bob Dylan mold, largely because Springsteen’s earliest songs likewise featured an overabundance of lyrics, delivered over lively acoustic tunes. Although he had his eye on becoming an all-out rocker with a full band, Springsteen relented and allowed his debut LP, “Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J.,” to feature more subdued material like “Mary, Queen of Arkansas” and “The Angel.” In turn, Hammond gave in and permitted Bruce to record two uptempo tracks — “Blinded By the Light” and “Spirits in the Night” — that included sax man Clarence Clemons and the rest of the soon-to-be E Street Band. Riding the balance between these two approaches were the three songs I admire most, which became staples in his live repertoire for the next few years: “Growin’ Up,” “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City” and the piano-based “For You,” which was often played at a much slower tempo in concert. Thanks to Cream and others, most aspiring British musicians in the mid-to-late ’60s became aficionados of the blues, or at least the blues-based rock that Cream had developed after hearing the original music of American bluesmen like Albert King, Buddy Guy and Robert Johnson. One of these ragtag groups was Jethro Tull, whose debut LP, the presciently named “This Was,” offered mostly blues stylings. But when flutist-singer-songwriter Ian Anderson pushed the group in a more rock/folk direction, original guitarist Mick Abrahams left the band and went off to form Blodwyn Pig to continue his interest in blues music. Their debut, “Ahead Rings Out,” reached the Top Ten in England, carried by Abrahams’ guitar and Jack Lancaster’s wailing sax on tracks like “Dear Jill” and “It’s Only Love.” The best song, in my opinion, was “See My Way,” which appears on the US pressing of the album but was left off the UK album and held back until the group’s second album, 1970’s “Getting to This.”

Thanks to Cream and others, most aspiring British musicians in the mid-to-late ’60s became aficionados of the blues, or at least the blues-based rock that Cream had developed after hearing the original music of American bluesmen like Albert King, Buddy Guy and Robert Johnson. One of these ragtag groups was Jethro Tull, whose debut LP, the presciently named “This Was,” offered mostly blues stylings. But when flutist-singer-songwriter Ian Anderson pushed the group in a more rock/folk direction, original guitarist Mick Abrahams left the band and went off to form Blodwyn Pig to continue his interest in blues music. Their debut, “Ahead Rings Out,” reached the Top Ten in England, carried by Abrahams’ guitar and Jack Lancaster’s wailing sax on tracks like “Dear Jill” and “It’s Only Love.” The best song, in my opinion, was “See My Way,” which appears on the US pressing of the album but was left off the UK album and held back until the group’s second album, 1970’s “Getting to This.”