Such a fine line between stupid and clever

I have a sheepish admission to make.

As a devotee of rock music of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, I have been called “a walking encyclopedia” of song lyrics, rock band trivia, chart success of albums and singles, and all manner of unusual anecdotes about rock culture of those years.

But I must confess: I never got around to seeing the celebrated 1984 rock documentary parody film “This is Spinal Tap” until two days ago.

In rock music circles, my failure to be hip to this movie would be regarded as unforgivable for a rock blog writer. It has gained its place as an iconic, can’t-be-missed gem that brilliantly satirizes both the rock music business as well as the documentary genre in general.

In rock music circles, my failure to be hip to this movie would be regarded as unforgivable for a rock blog writer. It has gained its place as an iconic, can’t-be-missed gem that brilliantly satirizes both the rock music business as well as the documentary genre in general.

So anyone who dismisses “This is Spinal Tap” as a silly cult film would be wrong. True, it took in a rather meager $4.5 million at the box office upon its release. But this unique and hilarious “rockumentary” has been widely praised by just about everybody who’s seen it (and thanks to video/DVD sales over the years, that number has grown significantly).

Consider this: “This is Spinal Tap” is ranked #29 on the American Film Institute’s “100 Best Comedies of All Time.” Entertainment Weekly included it on its “100 Greatest Movies” list, calling it “just too beloved to ignore.” Rotten Tomatoes gives it a 95% rating, with this critical consensus: “Smartly directed, brilliantly acted, packed with endlessly quotable moments. An all-time comedy classic.” Even the friggin’ Library of Congress deemed it “of aesthetic cultural significance” and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry!

Pretty damn solid credentials for a film that was shot in a month by a first-time director who had no script.

That director was the great Rob Reiner, who started his career as an actor playing Michael “Meathead” Stivic on the Seventies TV classic “All in the Family” and has gone on to direct such landmark films as “Stand By Me,” “The Princess Bride,” “When Harry Met Sally,” “Misery,” “A Few Good Men,” “The American President,””Ghosts of Mississippi” and “The Bucket List.”

That director was the great Rob Reiner, who started his career as an actor playing Michael “Meathead” Stivic on the Seventies TV classic “All in the Family” and has gone on to direct such landmark films as “Stand By Me,” “The Princess Bride,” “When Harry Met Sally,” “Misery,” “A Few Good Men,” “The American President,””Ghosts of Mississippi” and “The Bucket List.”

Reiner has comedy in his genes, thanks to his father, the legendary Carl Reiner, instrumental in early television sketch comedy on “Your Show of Shows” (1950-1954) and “Sid Caesar’s Hour” (1954-1957), as well as creator of the brilliant “Dick Van Dyke Show” (1961-1966) and director of several Steve Martin comedy films like “The Jerk” (1979) and “Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid” (1982).

Not surprisingly, it was a challenge getting “This is Spinal Tap” made in the first place. In those days, a TV actor who had the audacity to say he wanted to direct a film was laughed out of every Hollywood office he approached. But Reiner kept at it, eventually getting enough seed money to shoot a 20-minute demo of what he had in mind, and then shopping that around until Norman Lear, creator of “All in the Family” and other award-winning TV shows, agreed to back the project.

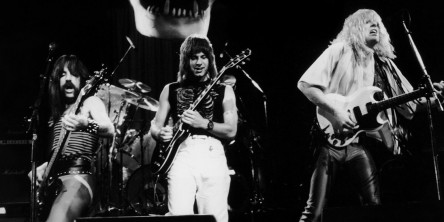

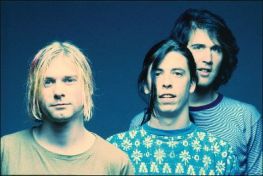

McKean, Shearer and Guest

Reiner had been friends with comic writer/actor Harry Shearer, and they teamed up in 1978 with Christopher Guest and Michael McKean, comedians who had originally been musicians, on a sketch about a parody rock band for a comedy show called “The TV Show.” The foursome decided to expand that simple sketch into a novel idea for a faux documentary about a British heavy metal band trying to make a comeback on what became a rather disastrous American tour.

“Chris and Michael had been improvising for years with these characters, playing up their British accents and their dimwitted naiveté,” said Reiner. “We put together a general arc of a story line, but when we shot the movie, we made it up as went along, because they were just so good at it. We often used the first take in the final cut, because it captured the natural reactions best.”

Cinematographer Peter Smokler, who had worked on rock & roll documentary films like “Gimme Shelter,” was brought in on the project. Says Reiner, “The whole time we were shooting, Peter kept turning to me and saying, ‘What’s funny about this? This is not funny. This is what they (rock musicians) do.’ And it’s true. Apparently, a lot of bands at that time were well-meaning but seemed so entitled, and genuinely clueless.”

“This is Spinal Tap” is mischievously witty without being mean-spirited as it tells the tale of an aging, pitiable, slowly disintegrating band, with an arrogant, ineffective manager, who try vainly to keep their hopes up even as they face the embarrassment of half-empty venues and cancelled gigs.

“This is Spinal Tap” is mischievously witty without being mean-spirited as it tells the tale of an aging, pitiable, slowly disintegrating band, with an arrogant, ineffective manager, who try vainly to keep their hopes up even as they face the embarrassment of half-empty venues and cancelled gigs.

It has an “is it or isn’t it real” quality that at first fooled many viewers into thinking Spinal Tap was a real band and the movie was a bonafide documentary. Hand-held camera techniques and deft editing between concert footage and backstage interviews made it look not all that different from actual rock docs like “The Last Waltz” or “Don’t Look Back.”

Reiner had seen how Martin Scorsese had put himself in his film “The Last Waltz” as its director, and decided to do the same thing. “I called myself Marty DiBergi, sort of combining Scorsese, Bergman and Fellini all rolled together.” He is seen interviewing band members and hangers-on backstage and at press events, and also introduces the film as its director at the beginning.

Much like “Animal House” and “Caddyshack” and other comedies of its era, “This is Spinal Tap” is riddled with quotable lines. One memorable scene has Guest’s guitarist character showing all the band’s equipment to Reiner’s interviewer character. He points  out that they have earned the reputation as “England’s loudest band” because they have amplifiers that can be turned up to 11. “All these other bands, they can only turn the volume up to 10, but when we need that extra oomph, we can go up one more notch,” the guitarist explains confidently as Reiner stares at him, puzzled.

out that they have earned the reputation as “England’s loudest band” because they have amplifiers that can be turned up to 11. “All these other bands, they can only turn the volume up to 10, but when we need that extra oomph, we can go up one more notch,” the guitarist explains confidently as Reiner stares at him, puzzled.

Reiner said he was dumbfounded when people asked him why he did a documentary of a band no one had ever heard of, a band that was so bad. “And I would have to say to them, ‘Um…Haven’t you ever heard of satire? You know, making fun of it all?’ And they would say, ‘Oh, okay…’ It took a while for people to catch up to it and realize it was all a spoof.”

Notorious party-boy rocker Ozzy Osbourne said he was among the audience members who assumed Spinal Tap was a real band. “When I learned the truth, I realized I should’ve known better. They seemed quite tame compared to what we were up to.”

In 2005, when U2 was being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, guitarist The Edge had this to say: “It’s been so hard to keep things fresh, and not to become a parody of yourself. If you’ve ever seen that movie Spinal Tap, you will know how easy it is to parody what we all do. The first time I ever saw it, I didn’t laugh. I wept. I wept because I recognized so much of ourselves in so many of those scenes.”

Said Shearer in 2002, “The cast and crew love to hear that, the musicians who have said, ‘Man, I can’t watch Spinal Tap, it’s too much like my life.’ That’s the highest compliment of all. It beats all the Oscar nominations we never got.” Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, Eddie Van Halen, Eddie Vedder, and Dee Snider are just a few of the musicians who have referenced similarities between their own lives and the movie.

Said Shearer in 2002, “The cast and crew love to hear that, the musicians who have said, ‘Man, I can’t watch Spinal Tap, it’s too much like my life.’ That’s the highest compliment of all. It beats all the Oscar nominations we never got.” Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, Eddie Van Halen, Eddie Vedder, and Dee Snider are just a few of the musicians who have referenced similarities between their own lives and the movie.

When he was casting “The Princess Bride” in 1987, Reiner said Sting, who had come in to audition for the part of Count Humperdinck, told him, “I’ll bet I’ve seen that movie 50  times. We wore out our video copy on the tour bus. Every time I watched, I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.”

times. We wore out our video copy on the tour bus. Every time I watched, I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.”

Speaking of casting, “This is Spinal Tap” includes some “don’t blink, you’ll miss it” cameos by well-known actors in bit roles. Billy Crystal, Angelica Huston, Fred Willard,  Fran Drescher, Ed Begley Jr., Howard Hesseman, Dana Carvey and Paul Shaffer all show up to add their two cents in the merriment.

Fran Drescher, Ed Begley Jr., Howard Hesseman, Dana Carvey and Paul Shaffer all show up to add their two cents in the merriment.

Much of the credit for the film’s effectiveness as a parody must go to the trio of Guest, McKean and Shearer for their spot-on performances as fading British rockers who are continually humiliated by the scheduling snafus and corporate disrespect they face. Guest, you may be aware, has had success in recent years imitating the mockumentary style of “This is Spinal Tap” in such critical favorites as “Waiting for Guffman” (1996), “Best in Show” (2000) and “A Mighty Wind” (2003), which he directed, co-wrote and appeared in. McKean, who got his start playing neighbor Lenny in the TV  show “Laverne and Shirley,” has appeared in nearly 70 films and 100 TV shows over the years, and currently plays older brother Chuck McGill on the “Breaking Bad” spinoff, “Better Call Saul.” Shearer, of course, has been one of the most important voices of characters on TV’s “The Simpsons” for two decades and running.

show “Laverne and Shirley,” has appeared in nearly 70 films and 100 TV shows over the years, and currently plays older brother Chuck McGill on the “Breaking Bad” spinoff, “Better Call Saul.” Shearer, of course, has been one of the most important voices of characters on TV’s “The Simpsons” for two decades and running.

These guys wrote and performed Spinal Tap’s musical numbers themselves, with help from a few session players, and truth be told, some of the songs aren’t much worse than the tracks you might hear on your average heavy metal album of 1984 (which isn’t saying much).

In the years since the film’s original release, Guest, McKean and Shearer have periodically reunited as their film’s characters and improbably turned Spinal Tap into an honest-to-goodness band that went on the road and into the studio. (A Spotify playlist below provides a decent sampling of their repertoire.) Their 1992 album “Break Like the Wind” reached #61 on the US charts, and 2009’s “Back From the Dead” peaked at a respectable #52. Said Guest, “We played the Pyramid Stage, we’ve played at Wembly, Royal Albert Hall, Carnegie Hall. It’s weird, but great. The fictional became real.”

In the years since the film’s original release, Guest, McKean and Shearer have periodically reunited as their film’s characters and improbably turned Spinal Tap into an honest-to-goodness band that went on the road and into the studio. (A Spotify playlist below provides a decent sampling of their repertoire.) Their 1992 album “Break Like the Wind” reached #61 on the US charts, and 2009’s “Back From the Dead” peaked at a respectable #52. Said Guest, “We played the Pyramid Stage, we’ve played at Wembly, Royal Albert Hall, Carnegie Hall. It’s weird, but great. The fictional became real.”

Art imitates life: The ’70s hard rock band Uriah Heep once found themselves having to perform at a lame Air Force base social event, an incident that Shearer chose to include in Spinal Tap’s itinerary.

Life imitates art: Heavy-metal titans Metallica said their 1991 LP “Metallica” (commonly known as “The Black Album”) is a tribute to the film’s scene where Spinal Tap’s record label replaced offensive artwork for its “Smell the Glove” LP with a plain black cover.

In one telling scene, Spinal Tap’s band members are angry about their album cover — a  photo of a naked woman on her knees restrained by a dog collar and leash — being refused, when another group is given permission for their cover, which instead features the band members in the same degrading position. When the difference is pointed out to them, they look at each other and say, “Hmmm. It’s such a fine line between stupid…and clever.”

photo of a naked woman on her knees restrained by a dog collar and leash — being refused, when another group is given permission for their cover, which instead features the band members in the same degrading position. When the difference is pointed out to them, they look at each other and say, “Hmmm. It’s such a fine line between stupid…and clever.”

So true. I suppose some people might find “This is Spinal Tap” monumentally stupid, but for those who appreciate finely tuned parody, I think it’s clever as hell. As someone who just viewed it for the first time in 2018, I think I could make the argument that this movie probably works better today than it did when it was first released. One of the movie’s goals was to satirize the concept of aging rockers engaging in “comeback” tours and albums, and, while there was plenty of that taking place in the early ’80s, it has surely become even more prevalent today. Heavy metal headbangers might look absurd on the stage in their 30s; how about when they’re old enough for Medicare?

By the 1990s, I was married, approaching 40, with children arriving, and both my time and my financial resources were being diverted (necessarily and/or enthusiastically) to other priorities. I wasn’t attending as many shows, buying as many albums (CDs at that point), nor reading as many books and magazines about the world of pop music, and I became less knowledgeable about new trends, new artists, even new technologies and music delivery systems. That detachment became even more pronounced in the 2000s, and still more here in the 2010s.

By the 1990s, I was married, approaching 40, with children arriving, and both my time and my financial resources were being diverted (necessarily and/or enthusiastically) to other priorities. I wasn’t attending as many shows, buying as many albums (CDs at that point), nor reading as many books and magazines about the world of pop music, and I became less knowledgeable about new trends, new artists, even new technologies and music delivery systems. That detachment became even more pronounced in the 2000s, and still more here in the 2010s. With all this in mind, I gingerly stick my literary toe in the water to write a piece this week that delves into the rock music of the 1990s. I realize my credentials to pontificate about this period are significantly shakier. My understanding, appreciation and experience with ’90s music is considerably more limited…but I believe my love of music in general, and my entitlement to an unvarnished opinion about any of it, allows me some leeway to offer my thoughts and preferences in this area.

With all this in mind, I gingerly stick my literary toe in the water to write a piece this week that delves into the rock music of the 1990s. I realize my credentials to pontificate about this period are significantly shakier. My understanding, appreciation and experience with ’90s music is considerably more limited…but I believe my love of music in general, and my entitlement to an unvarnished opinion about any of it, allows me some leeway to offer my thoughts and preferences in this area. were the big-voiced, melodramatic divas like Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, Toni Braxton and Celine Dion. There was still Hard Rock/Heavy Metal (Metallica, Def Leppard, Guns N’ Roses, Limp Bizkit) and an offshoot, Alternate Metal (Nine Inch Nails and Rage Against the Machine).

were the big-voiced, melodramatic divas like Whitney Houston, Mariah Carey, Toni Braxton and Celine Dion. There was still Hard Rock/Heavy Metal (Metallica, Def Leppard, Guns N’ Roses, Limp Bizkit) and an offshoot, Alternate Metal (Nine Inch Nails and Rage Against the Machine). There were the trailblazers, pretenders and new superstars of Hip Hop (Dr. Dre, M.C. Hammer, Snoop Doggy Dog, The Notorious B.I.G., Vanilla Ice, The Beastie Boys, Eminem, Puff Daddy). There were the newly “rocked up” country artists like Garth Brooks, Billy Ray Cyrus, Tim McGraw and The Dixie Chicks. There was, as always, dance music, from the likes of C+C Music Factory, Paula Abdul and ’80s phenoms Janet Jackson and Madonna.

There were the trailblazers, pretenders and new superstars of Hip Hop (Dr. Dre, M.C. Hammer, Snoop Doggy Dog, The Notorious B.I.G., Vanilla Ice, The Beastie Boys, Eminem, Puff Daddy). There were the newly “rocked up” country artists like Garth Brooks, Billy Ray Cyrus, Tim McGraw and The Dixie Chicks. There was, as always, dance music, from the likes of C+C Music Factory, Paula Abdul and ’80s phenoms Janet Jackson and Madonna. There were dozens of hungry “alt rock” (independent label alternative rock) bands with refreshingly quirky styles and approaches that tended to defy categorization: Dave Matthews Band, Oasis, Hootie and The Blowfish, Stone Temple Pilots, Indigo Girls, Gin Blossoms, Radiohead, Alanis Morissette, Goo Goo Dolls, The Cranberries, Counting Crows, The Smashing Pumpkins and Red Hot Chili Peppers.

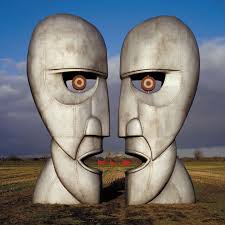

There were dozens of hungry “alt rock” (independent label alternative rock) bands with refreshingly quirky styles and approaches that tended to defy categorization: Dave Matthews Band, Oasis, Hootie and The Blowfish, Stone Temple Pilots, Indigo Girls, Gin Blossoms, Radiohead, Alanis Morissette, Goo Goo Dolls, The Cranberries, Counting Crows, The Smashing Pumpkins and Red Hot Chili Peppers. Of course, a few of the ’80s rock bands of substance were churning out great stuff a decade or more after their debuts: U2, R.E.M., Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers. And there were a handful of vintage rockers from the ’60s/’70s who could still top the charts in the ’90s (Pink Floyd‘s “The Division Bell” in 1994, Santana‘s “Supernatural” in 1999, Eric Clapton‘s “Unplugged” in 1992, Fleetwood Mac‘s “The Dance” in 1997, and The Beatles‘ “Anthology 1, 2 and 3” in 1995-96).

Of course, a few of the ’80s rock bands of substance were churning out great stuff a decade or more after their debuts: U2, R.E.M., Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers. And there were a handful of vintage rockers from the ’60s/’70s who could still top the charts in the ’90s (Pink Floyd‘s “The Division Bell” in 1994, Santana‘s “Supernatural” in 1999, Eric Clapton‘s “Unplugged” in 1992, Fleetwood Mac‘s “The Dance” in 1997, and The Beatles‘ “Anthology 1, 2 and 3” in 1995-96). The Judybats

The Judybats Sister Hazel

Sister Hazel Del Amitri

Del Amitri  James

James Top Ten LPs in the ’90s) and apparently still is — their latest album, “Girl at the End of the World,” almost beat out Adele’s “25” as the #1 LP in England in March 2016. Such great material to discover throughout the James catalog, and also on “Booth and the Bad Angel,” a 1996 collaborative project between Booth and “Twin Peaks” composer Angelo Badalamenti.

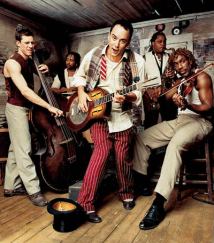

Top Ten LPs in the ’90s) and apparently still is — their latest album, “Girl at the End of the World,” almost beat out Adele’s “25” as the #1 LP in England in March 2016. Such great material to discover throughout the James catalog, and also on “Booth and the Bad Angel,” a 1996 collaborative project between Booth and “Twin Peaks” composer Angelo Badalamenti. My wife Judy was knocked out by her first exposure to this engaging blues artist at a House of Blues performance in New Orleans in 1996. (His name is Kevin Moore, but he goes by the street-talk abbreviation Keb’ Mo’ “just for fun.”) I ran out and bought his strong 1994 self-titled debut, an album that turned heads among Delta blues guitarists and songwriters. His 1996 LP “Just Like You,” which featured contributions from Bonnie Raitt and Jackson Browne, won a Grammy, as did its successor, “Slow Down” (1999). Now in his 60s, Keb’ Mo’ is a mainstay at the annual Crossroads Blues Festival and stays active in charity events, film projects and human rights initiatives.

My wife Judy was knocked out by her first exposure to this engaging blues artist at a House of Blues performance in New Orleans in 1996. (His name is Kevin Moore, but he goes by the street-talk abbreviation Keb’ Mo’ “just for fun.”) I ran out and bought his strong 1994 self-titled debut, an album that turned heads among Delta blues guitarists and songwriters. His 1996 LP “Just Like You,” which featured contributions from Bonnie Raitt and Jackson Browne, won a Grammy, as did its successor, “Slow Down” (1999). Now in his 60s, Keb’ Mo’ is a mainstay at the annual Crossroads Blues Festival and stays active in charity events, film projects and human rights initiatives. Beth Chapman

Beth Chapman New Radicals

New Radicals

The Verve

The Verve