Memories light the corner of my mind

“Music acts like a magic key, to which the most tightly closed minds open.” — Maria Augusta von Trapp

*****

The lady who inspired “The Sound of Music” got it right. Music — be it classical, folk, rock, jazz, blues, country, any genre you name — has a mysterious way of opening doors to the past.

Listening to songs from our childhood, our high school and college years, and our early adulthood has a way of bringing back vivid memories, many of them warm and pleasant, others more heartbreaking or melancholy. We may enjoy listening to more recent tunes on occasion, but newer music simply doesn’t have the uncanny ability to take us “back down memory lane.”

And that, in a nutshell, is why the use of music in the care of those suffering from Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia has shown such beneficial results.

Alzheimer’s tends to put people into layers of confusion, and a recently published study in The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease confirms that music can sometimes actually lift people out of the Alzheimer’s haze because it can stimulate undamaged regions of the various brain networks that determine what we can understand and remember.

“People with dementia,” explains study co-author Dr. Jeff Anderson of the University of Utah Health, “are confronted by a world that seems unfamiliar to them, which causes disorientation and anxiety. We believe music can tap into the salience network of the brain that is still relatively functioning, and bring them back to a semblance of normality, even if only for a short while.”

“People with dementia,” explains study co-author Dr. Jeff Anderson of the University of Utah Health, “are confronted by a world that seems unfamiliar to them, which causes disorientation and anxiety. We believe music can tap into the salience network of the brain that is still relatively functioning, and bring them back to a semblance of normality, even if only for a short while.”

******

“All my best memories come back clearly to me, they can really make me smile, just like before, it’s yesterday once more…” — John Bettis and Richard Carpenter

*****

“In our society,” Anderson continues, “diagnoses of dementia are snowballing. We are taxing healthcare resources to the max as we try to cut through the disorientation and reach these people. No one says playing music will be a cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but it might make the symptoms more manageable and improve a patient’s quality of life.”

A medical journal called Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine published a study of two dozen men living in a nursing home who had diagnoses of probable Alzheimer’s. It found that when the men were exposed to specific songs multiple times over several weeks, they demonstrated an improved ability to learn the melodies and the lyrics. The men also showed an increase in social interaction and more relaxed, calmer moods.

*****

“Music has healing power. It has the ability to take people out of themselves for a few hours, or find a part of themselves they thought they’d lost.” — Elton John

*****

My longtime friend Ginny Kallay is a board certified music therapist with nearly 40 years of experience in both pediatric and hospice care. She has watched people diagnosed  with dementia who have resisted communicating with family members and caregivers perk up when they hear familiar music.

with dementia who have resisted communicating with family members and caregivers perk up when they hear familiar music.

“It doesn’t work for everyone,” she says,” and when its does work, it may not last for long. But its can bring light to dark eyes. Music has a remarkable way of getting through.”

Kallay gets input from family members about specific songs they know are favorites of the Alzheimer’s sufferer. “There have been times when a patient hasn’t walked with or interacted with anyone for many days, but when they hear certain songs they recognize from their past, their mood changes. ‘You Are My Sunshine’ is an example. You see a light come on, a hint of a smile. They have a more positive focus. It’s really powerful.”

*****

“There is a tune that, every single time I hear it, makes me think of my cousin’s Sweet 16 party, where I played Spin the Bottle with a boy whose breath smelled like tomato soup. If you ask me, music is the language of memory.” — Jodi Picoult

*****

Kallay said she has found that music can also relieve stress for caregivers, whose lives have been made difficult by the frustrations of their loved ones’ unpredictable behavior and inability to communicate. “I have known spouses of Alzheimer’s patients who have been dealing with this for 10, 12 15 years. It’s exhausting, and demoralizing. These people need a lift, too. I’ve seen how music can relieve their distress, lighten their mood for a while, and connect with loved ones who have difficulty communicating.”

A hospice aide once told Kallay about a woman in her care who began reciting and singing words to a song Kallay had been singing to her eight hours earlier. “Sometimes the recognition or reaction doesn’t come right away. But the seed has been planted, and it blooms hours later. It’s amazing, really.”

*****

“Like sunshine, music is a powerful force that can instantly and almost chemically change your entire mood.” — Michael Franti

*****

Petr Janata, associate professor of psychology at University of California-Davis’ Center for Mind and Brain, conducted a study about how music might stimulate regions of the brain undamaged by Alzheimer’s and other dementias. “The hub of the  brain that music activates is located in the medial prefrontal cortex region, right behind the forehead, and one of the last areas of the brain to atrophy over the course of Alzheimer’s disease.

brain that music activates is located in the medial prefrontal cortex region, right behind the forehead, and one of the last areas of the brain to atrophy over the course of Alzheimer’s disease.

“What seems to happen is that a piece of familiar music serves as a soundtrack for a mental movie that starts playing in our head. It calls back memories of a particular person or place, and you might all of a sudden see that person’s face in your mind’s eye,” Janata said. “Now we can see the association between those two things — the music and the memories.”

*****

“Where words fail, music speaks.” — Hans Christian Andersen

*****

Music that we first encounter in our teens and early twenties tends to have the deepest impact and create the most lasting memories. For those now in their eighties, that would be the songs from the 1940s, 1950s and into the 1960s.

I can speak from experience about this. For a few years now, I have been volunteering a couple times each month at an adult day care facility here in Los Angeles, playing guitar and singing for elderly folks suffering from various physical or mental maladies, including dementia. The music I play is typically from the 1960s — songs by The Beatles, Simon and Garfunkel, Peter Paul & Mary, The Lovin’ Spoonful, Elvis Presley, among others.

For these seniors, hearing songs like “Yesterday,” “Homeward Bound,” “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” “Do You Believe in Magic” or “I Can’t Help Falling in Love” can burrow through the mental fog to a happy place in their memory. It’s so gratifying when I see a man or woman in the group who has been sitting still with a vacant stare suddenly start tapping their feet or smiling, or even attempting to sing along. Those who are able are  sometimes willing to rise from their chairs and do a little dance with a staff member, all because they hear a familiar song.

sometimes willing to rise from their chairs and do a little dance with a staff member, all because they hear a familiar song.

One woman I know has been slipping further into her Alzheimer’s fog, ever harder for caregivers to reach her and get her to respond to their overtures. Last month, as a staff member helped her get situated in a chair, I began playing the chords to Simon and Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson.” When she heard the chorus — “And here’s to you, Mrs. Robinson, Jesus loves you more than you will know, whoa whoa whoa,” — she visibly brightened, smiled up at me and began mouthing some of the words. It was so exhilarating to me that the music I was playing had the power to bring about that response from someone who is typically unable to respond much at all.

*****

“As the years roll on, each time we hear our favorite song, the memories come along, older times we’re missing, spending the hours reminiscing…” Graham Goble

*****

I’ve always marveled at how a song can instantly take you back to a specific time and place where you first heard it, or when a momentous event happened to you. This can  happen in everyone, whether or not you have suffered memory loss. The way music can work its way into your brain and trigger your memory banks is, in my opinion, nothing short of miraculous.

happen in everyone, whether or not you have suffered memory loss. The way music can work its way into your brain and trigger your memory banks is, in my opinion, nothing short of miraculous.

What a thrill, then, to be able to observe and participate as music helps those whose abilities to remember and communicate have been progressively impaired. I am grateful for the opportunity.

*****

“The times you lived through, the people you shared those times with — nothing brings it all to life like a mix tape of old songs. It seems to do a better job of storing up memories than actual brain tissue can do.” — Rob Sheffield

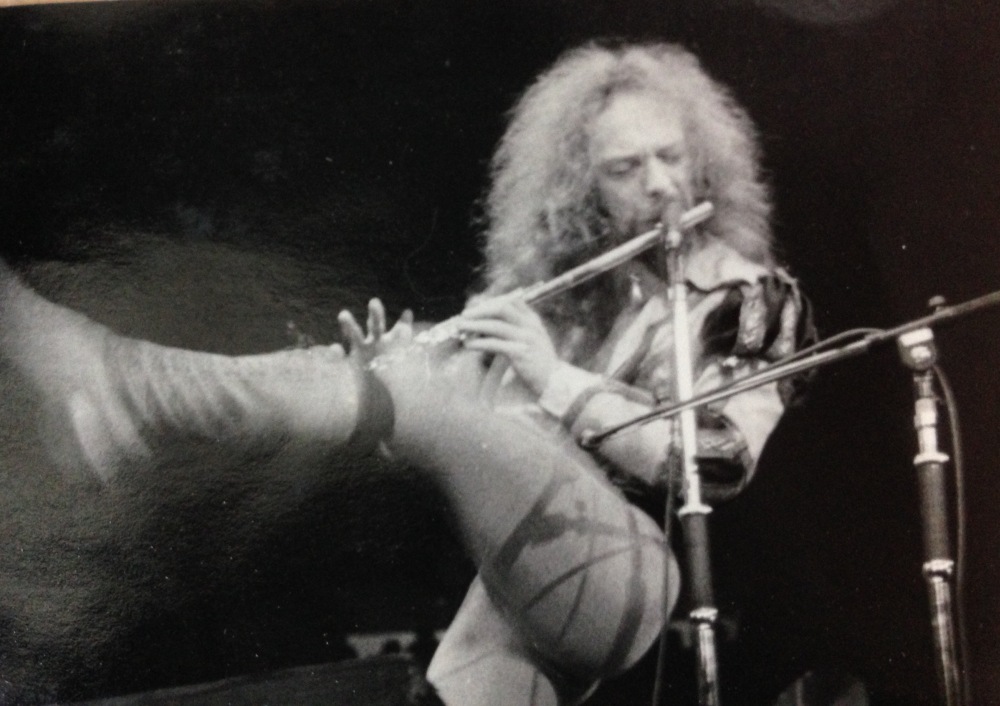

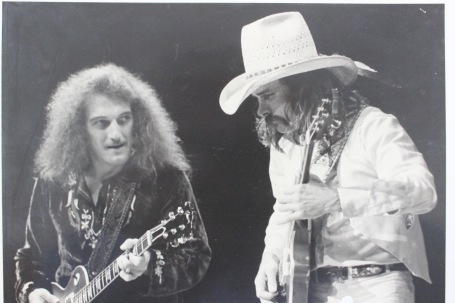

There are a few dozen photographers known far and wide for their excellent body of work shooting the top rock acts of the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s and beyond. Rolling Stone had the great Robert Altman; the Chicago scene had Paul Natkin; and in my native Cleveland, there was Janet Macoska, who’s been at it since 1974, documenting hundreds of concerts in the Rock ‘n Roll Capital. Last year, she published All Access Cleveland: The Rock and Roll Photography of Janet Macoska. I recommend you check it out. Her portfolio is exhaustive and truly extraordinary.

There are a few dozen photographers known far and wide for their excellent body of work shooting the top rock acts of the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s and beyond. Rolling Stone had the great Robert Altman; the Chicago scene had Paul Natkin; and in my native Cleveland, there was Janet Macoska, who’s been at it since 1974, documenting hundreds of concerts in the Rock ‘n Roll Capital. Last year, she published All Access Cleveland: The Rock and Roll Photography of Janet Macoska. I recommend you check it out. Her portfolio is exhaustive and truly extraordinary.